In Bangladesh, Rohingya refugees fleeing violence and persecution in Myanmar have sought refuge in Cox’s Bazar district where MSF has been providing medical services since 1992. The latest and the largest influx occurred in 2017, when nearly 700,000 Rohingya entered Bangladesh across the border. The overcrowded camps refugees have been contained to for almost seven years now. In recent years, we noticed rise of the injuries sustained because of violence, including targeted gun violence and stabbings by criminal groups, kidnappings for ransom, and further rise in violence between neighbors over the use of resources, such as water or land. In the Kutupalong hospital, there has been a 59% increase in violence related injuries in 2023. Limited access to severely over-burdened healthcare services has posed significant challenges for women’s health, including issues related to maternal care, family planning, sexual and reproductive healthcare and sexual and gender-based violence.

Rohingya women face a lot of barriers to accessing healthcare in the camps. In some camps, the movements of refugees within the camps have been restricted at night due to security reasons. Besides they face other various, such as being held at check points by the police, distance and lack of transportation in the camps, not having enough access to information about where to seek medical support and having limited knowledge about the danger signs during pregnancy. Rohingya girls face forced marriage, violence, and deprived of access to medical and psychological care and protection services.

Similarly, women from host communities in Cox’s Bazar and Dhaka, experience significant barriers to accessing healthcare due to their gender such as in a patriarchal society, women cannot make decisions for themselves easily. They have to rely on the decisions of men. As a result, they often do not receive timely medical care. Despite having adequate opportunities for education, they face various wrong treatments due to lack of medical knowledge. Despite the healthcare center being very close to some women homes, they fear about high amount of medical costs.

On World Health Day, we had conversations with our female staff and patients in Bangladesh to truly grasp the hurdles they face when accessing healthcare. These dialogues weren’t just about data; they were about understanding the very human experiences behind the statistics.

Hamida

A mother in MSF Kutupalong hospital

“I’m Hamida, from Moricchya, Cox’s Bazar. When I was pregnant, I knew I wanted the best care for my first baby child. Although there was a private clinic nearby, I had heard that MSF’s Kutupalong Hospital provided high-quality care, totally free.

Usually, my family has some reservations to seeing male doctors at the hospital as they prefer female doctors. I always accept their decision. We usually visit a nearby pharmacy if we have any physical issues as there is a woman who gives medication. This often keeps me away from seeking further medical care. However, financial barriers are another issue. We now have six people in my family. My husband is a farmer and drives a car sometimes. He is the sole earner in the family, and it’s tough to take care of six people. Even my older father-in-law and mother-in-law visit a nearby pharmacy for medication as it’s cheaper.

When I conceived, I decided to visit Kutupalong Hospital. My in-laws were not in favor of this as even the journey from Moricchya to Kutupalong would cost us money. I convinced my husband and started visiting with my mother for check-ups and follow-ups.

Thankfully, MSF’s experts were there. I had a safe delivery and gave birth to a healthy baby girl! I’m so grateful for their care and expertise.

In MSF’s Kutupalong hospital, we provide antenatal care, maternity and sexual and gender-based violence service.

Dr. Umme Salma

An MSF doctor

“I’m Dr. Umme Salma, an MSF doctor for the past 2 years. I see the firsthand challenges women in the Rohingya refugee camps and Bangladeshi communities face when they visit our facility for antenatal, maternity and post-natal consultation.

Many families in both communities aren’t aware of the risks of home delivery or the importance of regular checkups. This leads to complications and delays in seeking medical help.

Complications like retained placenta, hypertension, or the need for assisted delivery are frequently the result of late arrivals. This can be life-threatening.

At MSF, we provide essential care, but also make families aware of pregnancy risks and the importance of timely medical attention. We counsel husbands and wives to understand the needs of pregnant women.

Sadly, many mothers and babies lose their lives due to preventable complications. Raising awareness and improving access to healthcare is crucial.”

Sumaiya Shimu Kakoli

A midwife working for MSF

“I’m Sumaiya Shimu Kakoli, a midwife working for MSF. At our Kutupalong clinic, I see a critical need: supporting survivors of sexual and gender-based violence.

Sexual and gender-based violence survivors need medical attention within 72 hours of an assault, but fear and stigma often prevent them from seeking help. They worry about shame and social isolation, leading to delays in treatment. Many people are unaware of the possibility of becoming pregnant after such violence.

There are more difficulties for Rohingya women who are displaced from their motherland and took refuge in Bangladesh. Fear of being outsiders and limited movement within camps hinder access to health care.

We offer confidential services to all survivors, regardless of origin. Special sign like white flowers or the phrase “Mashir Ghor” help women access care discreetly. We provide medical attention, counseling, and medication.”

In MSF’s Kutupalong hospital, we provide care for sexual and gender-based violence, mental health and psychiatric services for both the refugees and host populations.

Halima

A mother from Goyalmara

“I’m Halima, a mom of three children from Goyalmara. Having access to healthcare made a big difference for my family.

When I had my first son, there weren’t any nearby hospitals for delivery in Goyalmara area. This meant a home birth. I know, it wasn’t ideal.

Things were not the same with my second son. This time, there were complications during the home birth due to sudden labour pains. My baby was underweight and had difficulty breastfeeding. I came to Goyalmara mother and child hospital immediately. MSF’s free care allowed me to stay in the hospital for almost two months until my baby became healthy.

In MSF’s Goyalmara mother and child hospital, our team provides sexual and reproductive healthcare – antenatal care, postnatal care, family planning, care for sexual and gender-based violence and mental health.

Tayaba

A mother in MSF Kutupalong hospital

My name is Tayaba, and I am from Modhurchorra, Lambashia. I am eight months pregnant. This pregnancy has been difficult with high blood pressure, swelling, dizziness, and nausea.

The closest health center wasn’t helpful, so I stayed home, unable to do chores.

The MSF clinic in Kutupalong is accessible only by local transportation, which is scarce. The long journey is especially difficult when you’re unwell. Thankfully, my husband found transport on time.

My previous child died during a complicated delivery. The baby was in a breech position, and he was injured during delivery. A few hours after the birth, the baby passed away. This incident made me sad.

When I got pregnant for the second time, I decided to make this long journey for the well-being of my baby and myself. My health is improving, but challenges remain.

We have to cross the checkpoints when we want to move from one camp to another and it also requires some medical documents which makes it more difficult to get care, especially at night. This discourages some from seeking timely medical attention.

My husband can’t always afford the travel costs. He occasionally turns to purchasing medications from the nearby pharmacy to avoid the trip.

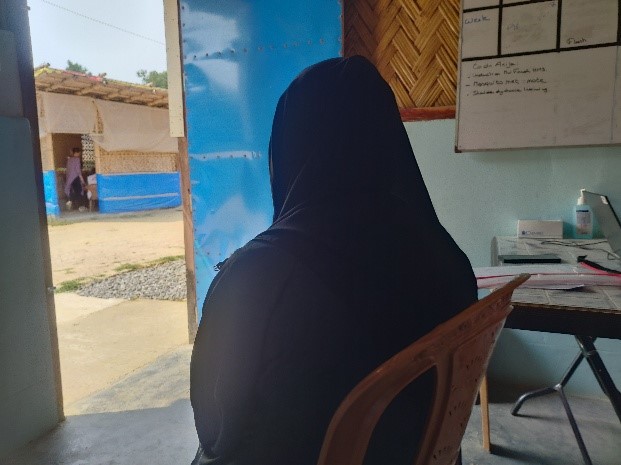

Jamila (Alias)

A staff at MSF clinic in camp 15,Jamtoli

“My name is Jamila (Alias). I work at the MSF clinic in Camp 15, Jamtoli. Women in this camp encounter numerous obstacles when attempting to access healthcare.

Camp security is a big issue for women. Due to violence in the camps, women are too scared to leave their homes, even for deliveries. Things have gotten calmer now and more women are coming to the clinic.

Another barrier is fear. Even though the camp is safer now, many women still have a deep fear from their experiences in Myanmar. They are terrified of leaving their homes at night, especially for emergencies, because of the gunshots and violence they have witnessed.

Women who are educated understand the importance of healthcare and are more likely to seek treatment at the clinic. But illiterate women, especially those who are very sick, often don’t realize the seriousness of their condition until it’s too late.

Despite these challenges, I see more and more women coming to the clinic, specifically for prenatal care. MSF Health Promotion Team also provides health education to women about diseases and healthcare options.”

In MSF’s Jamtoli primary healthcare centre, we provide 24/7 maternity, sexual and reproductive healthcare, comprehensive care for sexual and gender-based violence and mental health services.

Risalat Binte Aalad

A councilor educator in MSF’s Kamrangirchar project

I am Risalat Binte Aalad, a councilor educator in MSF’s Kamrangirchar project. Every day, I see women wrestling with the decision to seek help.

The first obstacle is simply realizing our existence. Women often come to discuss seemingly unrelated problems, and they don’t know about the services MSF provide until we have a careful chat with them. But even then, fear creeps in

Financial constraints are another barrier. Even a small sum for transportation can feel pressure. She is incapable of making the choice to come here on her own. Another source of stress for women is the constant questioning they get from family members about their whereabouts. Sometimes, violence erupts at home when they seek money for transportation.

The influence of family is strong. Many women, even adults are also incapable of making decisions about their own health care. They lack trust or capacity to handle things on their own and feel uneasy about the effects.”

In Kamrangirchar, MSF conducts more than 40,000 consultations for factory workers and their families, MSF has engaged with authorities to improve occupational health.

Anowara Begum

A housewife living in Balukhali Refugee camp

My name is Anowara Begum, 40 years of age. I live in Balukhali Refugee camp as a housewife. Life here in the camp can be difficult, especially when someone gets sick.

When going to the hospital, you can’t find anyone to help. If someone suddenly falls ill or when it is time to deliver a baby, you can’t find anyone to help. Then we ourselves have to rush to the hospital with the patient in our arms or on our shoulders. Sometimes, when we take the patient to one hospital, they send us to another hospital. The reason is that they don’t treat that disease or problem. As a result, we have to go to several hospitals. So, we try to take any sick patient directly to the Kutupalong hospital.

Another worry is money. Many families simply can’t afford the cost of hiring a vehicle. The nearest MSF facility is in Balukhali, it doesn’t provide all kinds of services now, so for serious illnesses, we have to travel far, like to Kutupalong Hospital. MSF provides free treatment, but they have to struggle to cover the cost of traveling so far.

For pregnant women, the struggle is even greater. Nearby hospitals often push for C-sections, which many women are uncomfortable with. They also try to pressure women into family planning methods after delivery, making them hesitant to go to hospitals altogether. Many of us feel it’s easier and safer to deliver babies at home.

In the past six years, the number of patients needing hospitalization has significantly increased. There seems to be a strong emphasis on promoting only long-term family planning, and patients may not be fully informed about all their options. This lack of information can be discouraging for those seeking healthcare treatment.

MSF Balukhali facility serves a large population of Rohingya refugees. In MSF Balukhali Specialized Outpatients Department (SOPD), our teams provide care for sexual and gender-based violence, sexual and reproductive healthcare and mental health services.

Nashima Pormin

A mother from camp 22, Unchiprang

I am Nashima Pormin, coming from camp 22, Unchiprang, to seek treatment for my son. He is suffering from pneumonia. When he got pneumonia, I knew I had to act fast.

At night, there is no transport inside the camp. This leaves families feeling helpless when illness strikes after dark. I didn’t want to risk my son’s life, so I got him admitted to Goyalmara Mother and Child Hospital. I had my son admitted to the hospital because I did not want to put his life at risk. My son and I traveled about 13 km from Unchiprang camp to the MSF clinic in Goyalmara, with the help of my brother and spouse. With MSF staff support, I was able to concentrate on my son’s healing.

During the first few days of his sickness, I gave him traditional homemade medicine (heated oil). I thought he would get cured of this. However, when I saw no improvement, I immediately took him to the hospital. MSF support allowed me to focus on my son’s recovery.

In MSF’s Goyalmara mother and child hospital, our team provides sexual and reproductive healthcare – antenatal care, postnatal care, family planning, care for sexual and gender-based violence and mental health.