Bombing, shelling and fear have escalated over the past months in Idlib governorate (northwest Syria), and nobody escapes the effects entirely. But for some people, additional health issues make life even more challenging.

There are also people willing to make a huge commitment to help these patients. Mohammad Al Youssef is a Syrian doctor. For the past five years, he has been working with Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), to provide life-saving treatment for people who have received a kidney transplant.

“Ten years ago, I underwent a kidney transplant. In that moment, I switched roles. I was not the doctor anymore, I became the patient. This operation turned out to be a decisive moment in my life, but also in my career.

An endocrinologist by training, I had, until then, focused mostly on the treatment of diabetes. My transplant, as well as the war that started two years later in my country, encouraged me to change my specialty. Today, I am one of the only doctors in northern Syria providing treatment for patients who have undergone a kidney transplant.

Before the war broke out in Syria, these patients’ treatment was quite straightforward. They were cared for would get taken care of in governmental hospitals or health centres. Everything was available and dialysis and medications were free of charge for kidney transplant patients. But in 2011, everything changed.

Checkpoints started to appear everywhere on the roads and people could not go in and out of their villages or towns to receive their treatments as they used to. Depending on where you were from, you could get arrested or even killed. It didn’t matter if you were sick… Coming from the wrong place could considerably complicate your movements and, by extension, your medical treatment.

Before the war broke out in Syria, these patients’ treatment was quite straightforward. But in 2011, everything changed. Checkpoints started to appear everywhere on the roads and people could not go in and out of their villages or towns to receive their treatment as they used to.

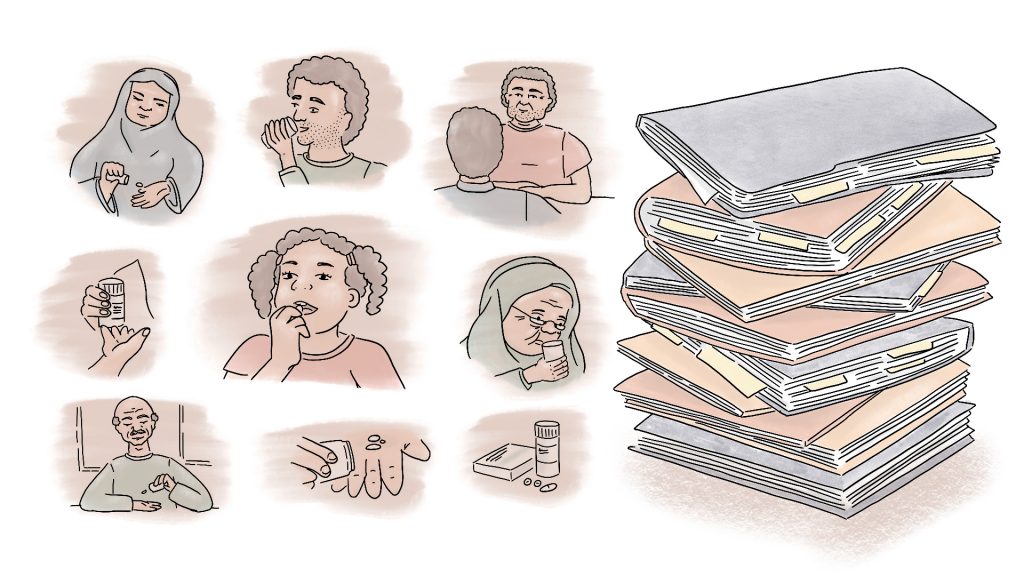

ILLUSTRATION BY LUCILLE FAVRE – MSF SWITZERLAND

All the people I knew who had received kidney transplants resorted to buying their own medicines or asking their relatives abroad to ship them to Syria. These drugs were their only means of survival.

After a kidney transplant, patients have to take immunosuppressants for the rest of their lives to prevent their bodies from rejecting the new organ. If they stop the medicine, patients go into kidney failure. If there’s kidney failure, they have to start dialysis.

Dialysis is a much less convenient but also a much more expensive form of treatment than taking immunosuppressants. For instance, when you sum up all expenses, the cost for dialysis, per patient, is around 450 US$ to 500 US$ per month.

In comparison, taking immunosuppressants doesn’t usually cost more than 150 US$ or 200 US$ per month. But even that is a huge amount of money for people in Syria. It’s more than an average person’s monthly salary and most patients simply can’t afford it.

MSF agreed to support these patients and to provide, free of charge, the treatment that would keep them alive.

ILLUSTRATION BY LUCILLE FAVRE – MSF SWITZERLAND

That’s why, in 2014, I decided to reach out to MSF, with the help of local health authorities.

I knew the organisation was conducting a similar programme in Homs governorate, which encouraged me to contact them. I told MSF that I knew 22 kidney transplant patients who were unable to afford their medication and I provided the organisation with their medical files.

MSF agreed to support these patients and to provide, free of charge, the treatment that would keep them alive. This made me incredibly happy. As a kidney transplant recipient, I wanted to support the patients morally but also help, as much as possible, practically. Since the beginning of the war and until then, the situation of these patients had been completely overlooked by most humanitarian organisations.

The group of patients I started to follow grew over the next few months and years From 22 patients, I started to treat 45, then 73 and then almost a hundred!

ILLUSTRATION BY LUCILLE FAVRE – MSF SWITZERLAND

The group of patients I started to follow grew over the next few months and years. Through word of mouth mostly, more and more kidney transplant patients started to reach out to me to benefit from the donation of medications.

This shows how much such support was needed. From 22 patients, I went on to treat 45, then 73 and then almost a hundred!

In 2015, another humanitarian organisation replicated the same activity in Aleppo governorate and asked me to help there too. I started sharing my time between MSF and this second organisation, overseeing the treatment of over a hundred patients in the north of Syria. Some of my patients, displaced by the conflict, come from other parts of the country.

When people talk about Syria, we often hear about wounds and trauma injuries. There is little to no focus on what the situation can be like for patients who have undergone a transplant and now need life-saving treatment.

ILLUSTRATION BY LUCILLE FAVRE – MSF SWITZERLAND

Taking care of these patients for the past five years has changed me. When people talk about Syria, we often hear about wounds and trauma injuries. There is little to no focus on what the situation can be like for patients who have undergone a transplant and now need life-saving treatment.

Since 2014, the work that I have accomplished has brought me relief and satisfaction, but if I am completely honest, I am also very tired of working and living in such a challenging situation. I even wanted to give up at some point but my patients did not give up on me. They told me that I had to continue, they didn’t have anyone else to rely on.

Today, in Idlib, the context is particularly bad and the war is far from over. We can’t know what the future holds because everything changes every day.

The only thing I’m now sure of is that I will not give up my work, for as long as my patients need treatment. I cannot abandon them and I’ll continue to do this job until I am sure they are safe. These people don’t care about war; they just want to live a normal life. Providing this treatment is the only way to make this possible and to ensure their survival.”