Diabetes ranks among the top 10 causes of death globally and affects over half a billion people worldwide. Over 80% of those affected live in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).

Insulin pens and newer diabetes medicines can simplify treatment and reduce complications for people with diabetes. While these tools are widely available in high-income countries, access in LMICs and humanitarian settings is extremely limited, due primarily to their higher prices.

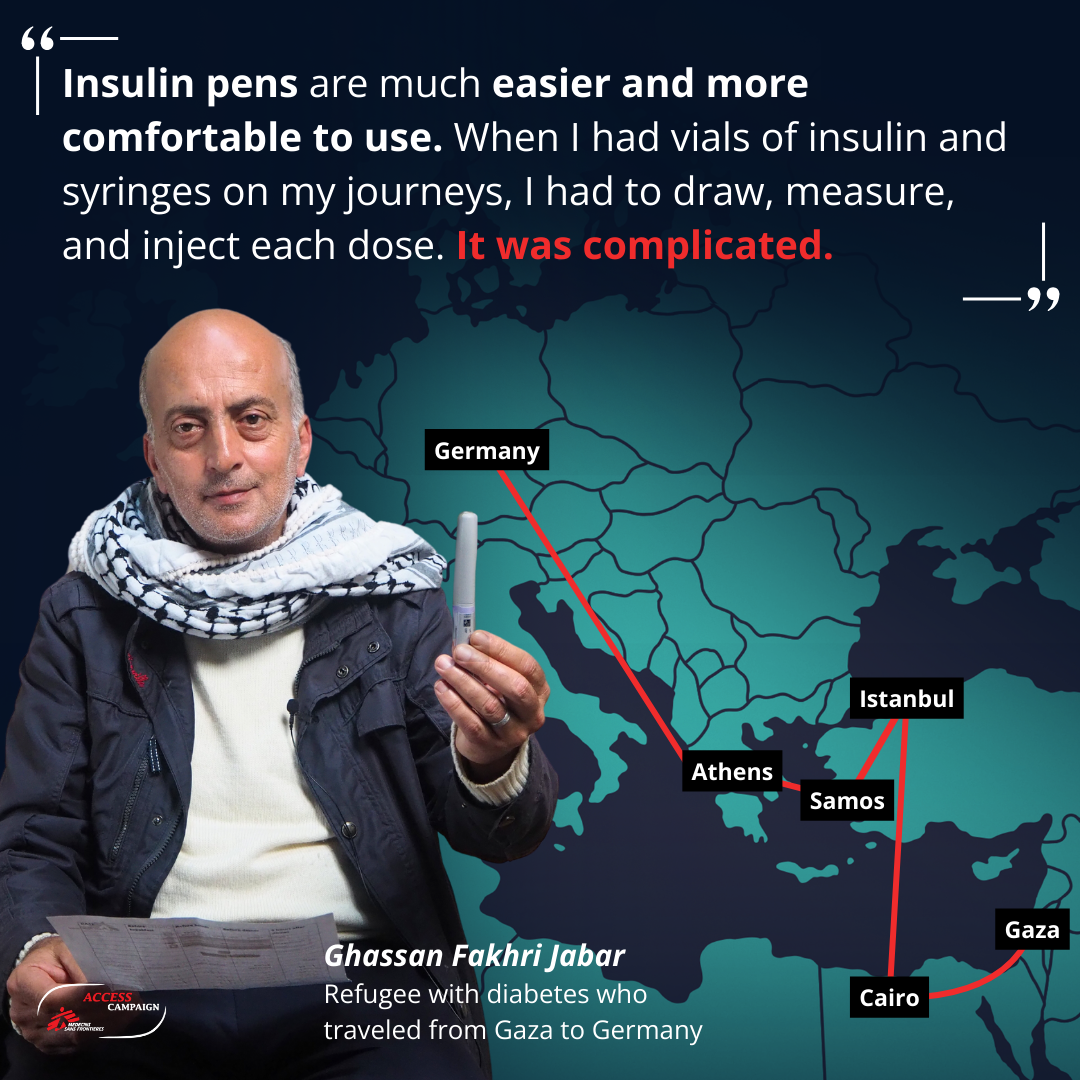

In our advocacy for better access to insulin pens for people with diabetes in low- and middle-income countries and crisis settings, we are sharing the stories of three individuals who traveled to Greece while managing their diabetes. Each person explains how insulin pens are easier to carry and use, especially in difficult situations, compared to vials and syringes.

MSF has significantly increased the number of diabetes consultations in its medical programmes: in 2022, MSF performed 205,122 diabetes-related consultations globally. All three people sharing their stories were receiving treatment from MSF in Athens, Greece.

Managing Diabetes Through My Journey to Europe

Ghassan Fakhri Jabar

Ghassan Fakhri Jabar carefully puts the coffee cup down. There’s an atmosphere of pent-up excitement in the small apartment where we are talking in Agios Panteleimonas, a vibrant and multicultural part of Athens, the Greek capital.

Ghassan has been living here for four months now, after undertaking a long journey from Palestine to escape conflict.

Children and grandchildren are running around the apartment, daughters, wives and daughters-in-law from the extended family are preparing food in the tiny kitchen, laughing and chattering together, while trying to keep the children in some kind of order, so the father can tell their story. Around the rooms of the apartment, suitcases and bags are piled up, packed and ready to go.

On Friday, Ghassan will set off on the last leg of his journey from Gaza to Germany, where two of his sons and their families are eagerly awaiting the reunion with their father and the rest of the family.

It’s a familiar story of flight, exile and the dream of family reunion. But the journey Ghassan has just taken, was made far more dangerous by the fact that he lives with type 2 diabetes, and needs to control his blood sugar levels with a strict routine of tablets and insulin.

Without regular monitoring of his blood sugar levels, and insulin injections, Ghassan risks falling very ill, or worse. In a journey of over eight months from Gaza, through Turkey, to the Greek island of Samos, and finally to Athens, Ghassan has been through some desperate and challenging moments on account of his medical needs as a person living with diabetes. We asked him to share his story.

“I was a simple man, a government employee in Gaza. My two sons left for Germany and four years later, I decided we should all leave Gaza and go there to support them. I’d been diagnosed with diabetes around 15 years earlier, and was receiving insulin in vials regularly from UNWRA (The United Nations Relief and Works Agency) for free. My life was in order and my illness controlled. When I told UNWRA that I was planning to leave Gaza and travel to Germany, they gave me a two months’ supply of insulin in vials with syringes to take with me.

In all there were thirteen of us, travelling together. I sold my car, put my financial affairs in order and we left Gaza through the Rafah crossing, and then by bus to Cairo airport and flew to Sabiha (Istanbul) airport in Turkey.

When we got to Turkey, we planned to travel to Greece together, but I didn’t have enough money. So, I sent my youngest children and my married children ahead of us on to Greece. My wife, daughter and myself remained behind. We didn’t know it would take us eight months and 15 failed attempts before we would complete the journey to Greece.

Back in Palestine, I was taking my diabetes medication consistently and keeping my blood sugar levels regular. That stopped when I got to Turkey. When the insulin in vials given to me by UNWRA ran out, I tried to buy some more, but it was too expensive. When the insulin was unavailable, I tried to adjust to my circumstances, I reduced my food intake and exercised and walked around in order to try to keep my blood sugar levels down. I deprived myself of many foods, drank a lot of water and tried to eat healthy things like tomatoes and cucumbers. But basically, I didn’t have enough money to buy anything much to eat.

During this time, we made many attempts to cross over to Greece, paying smugglers. Fourteen times we set out by boat, and each time the Turkish Coast Guard caught us. They took all our bags of belongings, clothes, food, and my medications, and threw them in to the sea, before sending us back to Turkey.

I was sent to prison for three or four days each time we were caught. They gave us a piece of bread with cheese the size of my palm, the same meal for breakfast, lunch and dinner for several days. This food wasn’t healthy for someone in my condition, so I tried not to eat it in order not to raise my blood sugar levels. Sometimes my blood sugar would fall to 60 (a dangerously low level) and then I would fall into a coma. They would take me to hospital and give me treatment to raise my sugar level. They didn’t want me to die in prison. Then they sent me back to prison. Sometimes, though, the hospital refused to treat me because with a blood sugar level of 700, they considered me dead already and they sent me on to another hospital. When they stopped detaining me and took me back to the camp where we stayed, they told me to manage on my own.

Ghassan and his family finally made a successful crossing to the island of Samos on their 15th attempt.

Upon arrival in Samos, the police escorted us, and we were taken to get a medical check-up. I told them I was diabetic, and they tested my blood sugar, which was 600 (a dangerously high level). They called an ambulance and transferred me to the hospital immediately. I spent the night there before returning to the camp on the island where I started taking insulin daily at 10 AM in the mornings.

When we left Samos, two and a half months later, and came to Athens, I was directed to the MSF clinic. They checked me and found my blood sugar was high. The chronic disease doctor gave me insulin pens and monitored my condition every 15 days. I recorded my blood sugar levels in the morning, afternoon, evening and after dinner.

The insulin pens are much easier and more comfortable to use. When I had vials of insulin and syringes on my journeys, I had to draw, measure, and inject each dose. It was complicated. Obviously getting access to any insulin was the main thing, but it would have been so much easier for me with pens, which are convenient, and the injection is light and painless. I appeal to the whole world to support MSF in continuing to provide insulin through pens, not vials.

The MSF doctor was strict with me, emphasising the importance of caring for my health. He cared a lot about me and was kind. I am very grateful for what he did.

Thank God I adhered to the programme he set for me and took the insulin regularly and my blood sugar readings in the fourth month were excellent. I was lucky to be able to store my insulin in the fridges of the local supermarket. People locally have really helped me.

Now I’m ready to move on. And this time I am prepared. Dr Fanis gave me two months’ worth of insulin pens. My advice to people with diabetes is that if you have to travel, make sure you stay in touch with a doctor, take insulin without interruption and avoid stress and anger.

I’m ready now. You must challenge the disease, or it will defeat you. I challenged the whole world to reach my children. I faced death for their sake. Now, thankfully due to God’s grace and the doctor’s help, my life is now well organised and healthy. I feel successful. My children are eagerly awaiting us. They feel we did our utmost for them and were in their service. Thank God.”

After the interview, Ghassan decides to stretch his legs, and introduce us to his friends in the locality. Soon, this time in Athens will be just a faded memory, but there’s still time to share a final coffee and enjoy the company of friends, so many of whom have shared experiences of traumatic journeys, fleeing unstable and conflict-ridden homes, and now facing uncertain futures. In an ever-changing and unpredictable world for Ghassan and so many others like him, the value of family and friendship is the only constant.

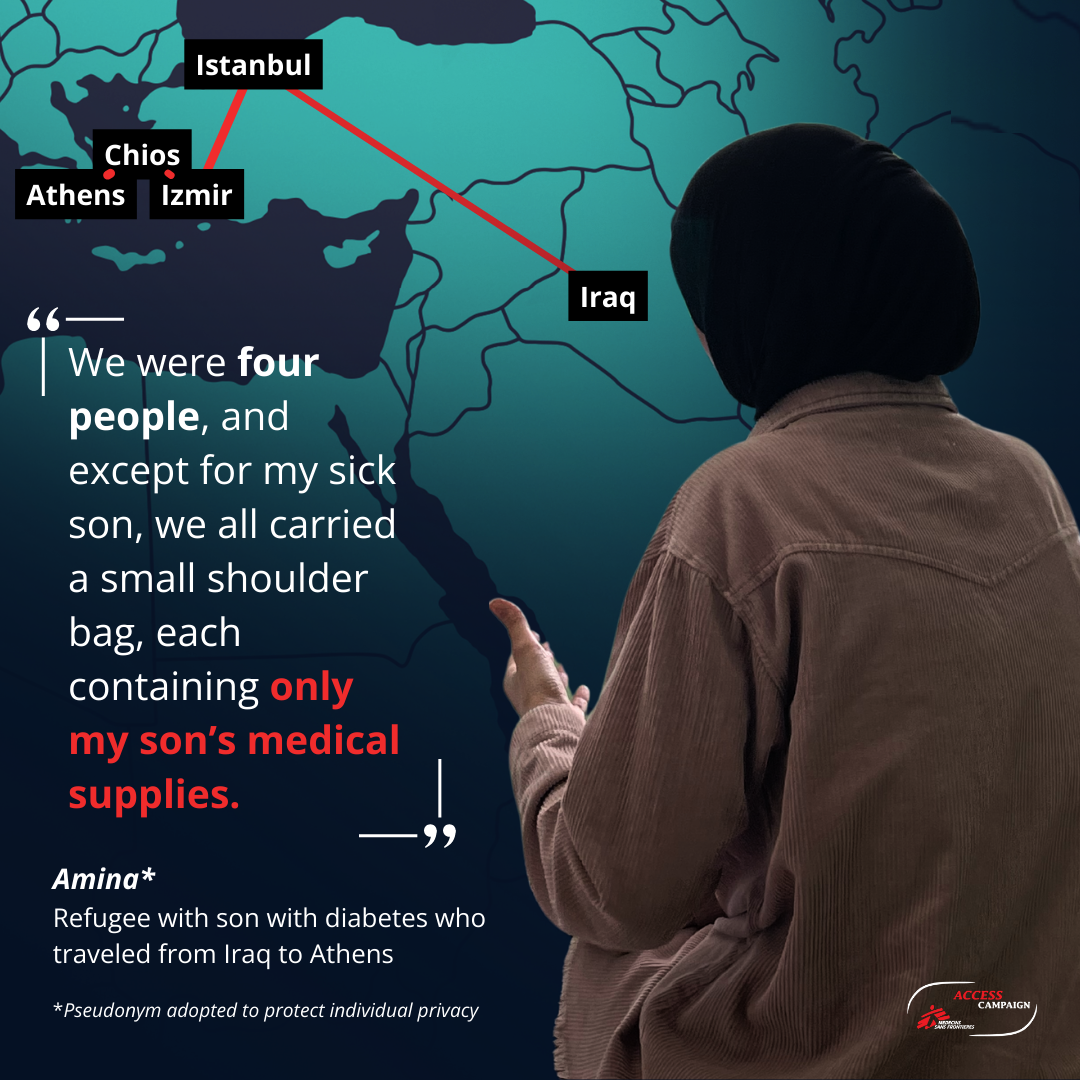

Amina

Sitting in her sunlit, mint-green kitchen in Athens, Amina* shares the difficulties she faced in managing her son’s type I diabetes on her own in Iraq, and how in spite of what she knew would be an extremely challenging migration journey from Iraq to Greece with three young children in tow, she fled her abusive husband.

Do not think that the decision to travel was easy with children and a sick child. The only reason I travelled was my husband.

My son, Ehsen*, was seven years old when I first noticed changes in him. He started wetting the bed, which he had never done before, and his appetite increased. I immediately took him to a doctor, and he was diagnosed with type I diabetes and provided with insulin injections to manage his diabetes.

In the beginning, insulin pens – which are much easier to use – were not widely available in Iraq, so Ehsen had to use injections (with an insulin syringe and vial), and I had to inject him myself. The syringes were difficult because I was not experienced in administering them. It caused me great pain to inject my child, especially since he was so young and sometimes cried. Many times, I cried before he did.

After his diagnosis, I brought Ehsen’s medical records to his school to inform them of his diabetes and ensure he would be properly cared for. However, with 47 students in a class, the principal told me they would not be able to care for Ehsen and so he was forced to drop out of school.

I felt deep sadness and anguish for my child, because although Eshen’s diagnosis was quick, his health was not stable. His hospital visits were frequent and numerous.

Later, Ehsen began experiencing unstable blood sugar levels, which would rise and fall repeatedly. When his sugar level dropped, he would faint. If high, he required long hospital stays to improve his condition.

For me, coping with this was very difficult. I had no support. I was an orphan before I got married, and my husband’s membership in a local militia and violent acts in our community made people avoid me. At home, my husband’s treatment was worse. He was violent, he beat me, and I had to have several surgeries; but I did not fear for myself. I feared for my children and their future.

The decision to travel with three children, one of whom was sick was not easy. First, I consulted my children despite their young age. I sat with them and told them I wanted to take this step for their safety, to protect them from the violence of their father. I asked them if they were okay with it and they told me, “We will be with you on your chosen path.”

Then, when my husband was on a month-long training course, I went to a travel office and told them I wanted to travel to Turkey. I took some money and only two insulin pens for my son and we left (the average number of pens used in a month is 5).

At the airport, I had to plead with an officer to let me and my young children on the plane. Eventually, he took $300 and let me through but our plane was delayed, and I was terrified my husband had returned and was looking for me. I felt like I lost half my life waiting for that flight.

In Turkey, I was a stranger and did not know the language or where to go, but although things got easier, Ehsen soon had no more medication. His condition worsened and he was hospitalised. He spent a month and thirteen days in hospital. During this time, I learned my husband was looking for me and knew we had to leave.

Knowing my situation and living conditions, the hospital discharged us with enough medication and insulin pens for six months, a blood sugar monitoring device, and even a container with fruit and milk.

When we reached the coast to travel by boat to Greece, the smuggler saw me and said, “What are all these bags? How will you cross with them?” I told him these were my bags. He said I had to leave them and only carry a small shoulder bag. We were four people, and except for my sick son, we all a carried small shoulder bag, each containing only his medical supplies.

Unfortunately, our first attempt failed, and we returned halfway before reaching Greece. Living through this was not easy, but we tried again. During the journeys, my son was taking his medication, but it was not regular. When we arrived in Greece, he was again hospitalised.

Once we reached Greece, I applied for asylum. This allowed my family, and especially my son, health insurance so he could go to the hospital and get treatment. However, we were rejected twice, our insurance was stopped, and I couldn’t buy medication for Ehsen. That is how I reached MSF about a year ago, as through them I can access free medication, including insulin pens, for my son.

Thank God my son can now take care of himself and manage his treatment. This is especially because using pens is much easier, whereas the syringe requires someone to help.

It has been six years since we arrived in Greece, and only now my fear and anxiety for my son have increased. This is because I never expected the second rejection of my asylum application. Their excuse was that Iraq was a safe country, and I could return. My lawyer and I explained my situation and family condition. I am currently waiting for a response to a new file, which will be the final and decisive response: I hope to have official papers because that will bring back medical insurance.

You might think from my talk that these are ordinary events, but living through it is not easy. Exile is difficult and takes away from a person’s life. If not for the harsh and challenging circumstances with my husband, I would not have left my home and country. Anyone with diabetes who takes a journey like this should think through every step and consider securing treatment because it is not easy.

In the end, all I want is to ensure my children’s future in a country that will embrace and care for them.

*Pseudonyms have been adopted to protect individual privacy.

In this final of three stories, we hear from people living with diabetes who have made difficult journeys while trying to manage their diabetes treatment. All three patients were receiving treatment from MSF in Athens, Greece.

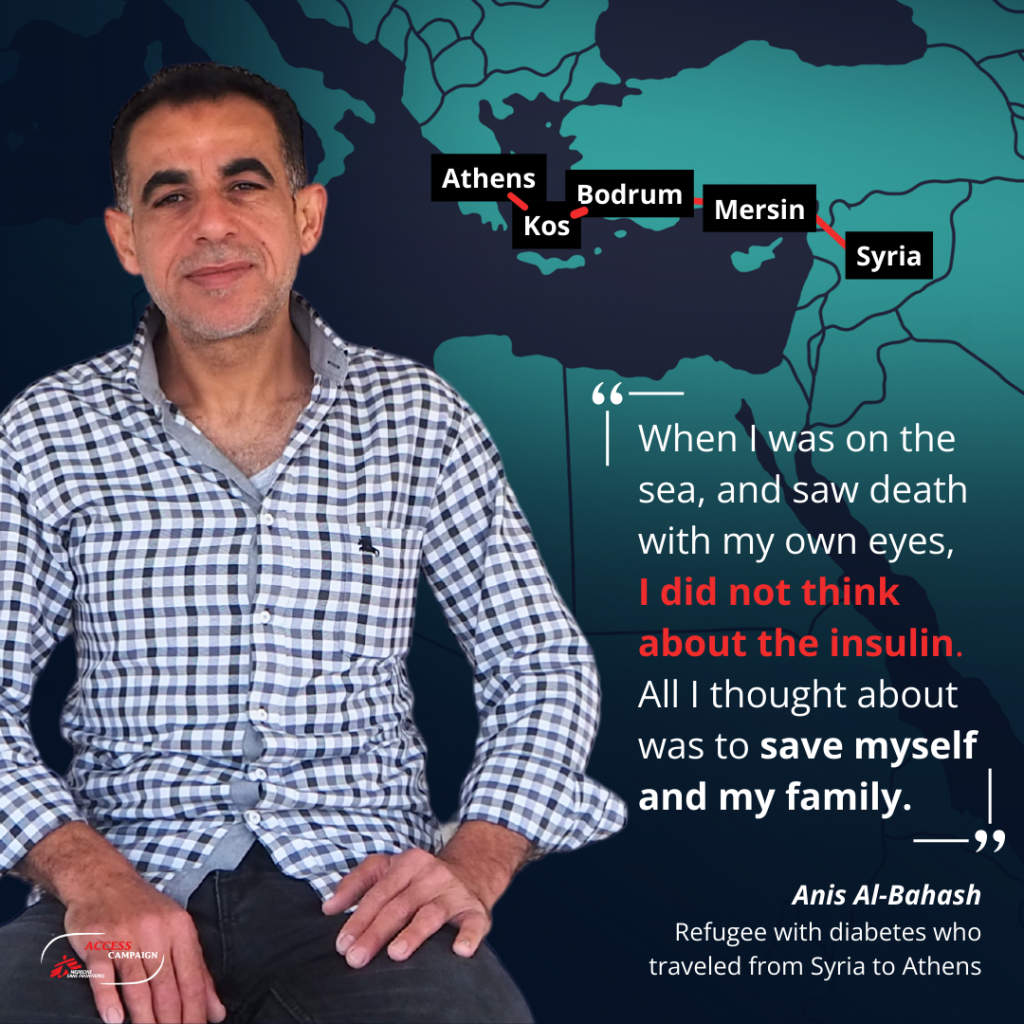

Anis Al-Bahash

The air shimmers in the early morning Athenian heat. A slight figure moves towards us, walking slowly along the high sunbaked walls that surround Schisto, the refugee camp situated on the outskirts of the Greek capital. Schisto has been Anis and his family’s home since they arrived as refugees from Syria, seeking asylum in Europe. As Anis comes in to focus, he looks a great deal older than his 51 years. That’s understandable given the journey he’s undertaken to get here from war-torn Syria. But Anis carries an additional burden, as he was diagnosed with diabetes on his journey and had to follow a strict routine of medicines, including insulin injections every day, to stay alive and healthy. Diabetes is a complicated disease to manage and during his journey to Greece, Anis encountered a number of challenges. Now in Greece, he is finally getting his insulin in a pen which makes his treatment simpler and safer. We asked Anis to share his story.

I was forced to leave Syria and lost everything I owned in the war. We were under siege, and we did not have any food. I had a newborn baby. So, we decided to leave Syria and faced many difficulties before we could get to Turkey. We finally arrived in Mersin (on the southern coast of Turkey) and, since we had no more money, we stayed on there.

When we first arrived, we had to sleep in gardens, as we had nowhere to stay, and to ask friends to help us. Over time we met people who helped us secure shelter. Then, finally we started working and I was able to rent a house and begin a new chapter. Unfortunately, after a short time, the landlord threw us out with our belongings on to the street. That’s the time that I started developing symptoms. The feeling was indescribable, a feeling of deep fatigue and sadness. I felt body tremors, and my weight began to decrease sharply.

I went to a doctor who told me I had to take insulin immediately because my blood sugar level was very high. So, I bought some insulin and started injecting it. After that I consulted another doctor who told me I needed a device to measure blood sugar and should take my insulin doses based on that. I suffered a lot. Any disease that affects the body is very difficult in the beginning and over time one starts to adapt.

I injected insulin three times a day. Sometimes the blood sugar level would get very high, reaching up to 500, due to the lack of accuracy in the doses I was injecting, and the stress I was under. My financial situation did not allow me to eat regular meals (as I should) either. I felt pain in all my bones and every part of my body.

Unfortunately, when circumstances are difficult, one clings to any hope or opportunity for change, so we finally decided to leave, travel through Turkey and try to get to Greece. I went without insulin for three days during this part of my journey, and I did not eat for fear of increasing my sugar levels. When I saw the sea, I did not think much about the illness or insulin. All I thought about was to save myself and my family. At the moment when I was on the sea, and saw death with my own eyes, I did not think about the insulin either. But I thought about it soon after we arrived.

Unfortunately, when circumstances are difficult, one clings to any hope or opportunity for change, so we finally decided to leave, travel through Turkey and try to get to Greece. I went without insulin for three days during this part of my journey, and I did not eat for fear of increasing my sugar levels. When I saw the sea, I did not think much about the illness or insulin. All I thought about was to save myself and my family. At the moment when I was on the sea, and saw death with my own eyes, I did not think about the insulin either. But I thought about it soon after we arrived.

When we got to Athens, I was transferred to this camp. At the camp they also asked about my illness and the type of medications I had. I had one remaining injection of insulin left. So, they made appointments for me at the public hospital and provided with me insulin.

My application for asylum was turned down by the Greek authorities and that meant that I lost the right to access health care in the Greek health system. All my medical procedures were stopped. Insulin was stopped, and I was desperately in need of it.

On that same day, I met someone from MSF in the camp, I didn’t know they were present. MSF supported me and gave me the insulin – in pens – that I needed.

For someone with diabetes who uses insulin, the pen is necessary. The pen is definitely easier.

I don’t know what to do. I live day by day and do not know what will happen tomorrow. This illness has affected all of our family greatly. There has been constant suffering.

The same week as this interview was recorded, MSF extended its project to support people with diabetes for a few more months.