An estimated 1 million people die each year from HIV/AIDS, while nearly 2 million people become newly infected with the virus.

Approximately 36.9 million people were living with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) at the end of 2017, the majority of them in sub-Saharan Africa. While there is no cure for HIV/AIDS, a combination of drugs, known as antiretrovirals (ARVs), enable people to live longer, healthier lives. The cost of first-line drugs are now cheaper than ever, but efforts are still needed to ensure everyone who is living with HIV receives treatment. Over 15 million people missed out on receiving treatment in 2017.

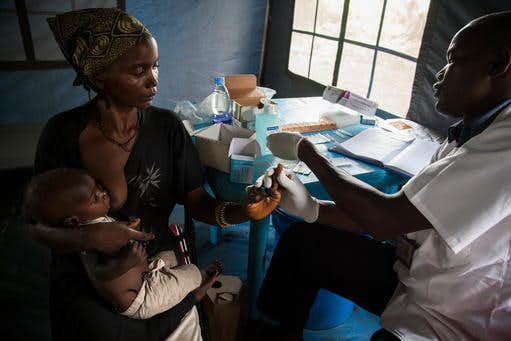

Worldwide, around 30 per cent of people currently infected with the virus don’t know their HIV status. In West and Central Africa, less than half of people living with HIV have access to testing. Once someone is diagnosed with the disease, viral load monitoring – measuring the levels of HIV virus in the blood – is essential to ensure that treatment is working. While routine viral load tests are standard in wealthy countries, access in developing countries still lags far behind.

There is no cure for HIV, although life-long treatments using combinations of drugs known as antiretrovirals (ARVs) help combat the virus and enable people to live longer, healthier lives. While double the amount of people are on treatment today than what there were around five years ago, deadly treatment gaps exist, especially in West and Central Africa, and the Middle East and North Africa, where barely a quarter of people living with HIV receive ARVs.

While most people can stay healthy on first-line drugs – which cost around US$80 per person per year – others may become resistant to this regimen and have to switch to second-line regimens. But the price of doing so is high – literally. Second-line regimens are nearly four times the price of first-line regimens. To switch from second- to third-line regimens is up to eight times more expensive, as much as $2,200 per person per year. On top of overcoming pricing barriers, adequate medical follow up must ensure a timely identification of resistance and a switch of regimens when needed.

Low HIV prevalence rates – ranging from two to 10 per cent across West and Central African countries, and less than one per cent across the Middle East and North Africa – have left these regions in a blind spot in the global HIV response. These regions lag far behind in attention and investment in tackling the epidemic, resulting in low access to testing and treatment (only around a third in West and Central Africa). It is unacceptable to witness people dying of AIDS within hours of being admitted to our hospitals.

In conflict settings and when people are displaced, ensuring the continuity of care for people with HIV – including a constant supply of drugs – can be difficult. Logistical and security issues are barriers for both our teams and patients in ensuring that people living with HIV can access the care and treatment they need to stay healthy. In Yemen, providing uninterrupted treatment during more than four years of war has proved logistically challenging – and dangerous to patients and staff.

HIV lowers the body’s immune response, and without effective treatment, leaves people living with the disease much more vulnerable to deadly opportunistic infections like tuberculosis (TB). TB is the single biggest killer of people living with HIV, with more than 400,000 dying each year. However, according to WHO, only one in four people living with HIV estimated to have developed TB in 2016 had access to ARV treatment.