A study carried out by Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) indicates that almost 20 per cent of the Rohingya refugees tested in the Cox’s Bazar camps in Bangladesh have an active hepatitis C infection.

A blood-borne virus, hepatitis C is a disease that can remain dormant for a long time in those infected. If untreated, it can attack the liver and lead to serious or even fatal complications, usually cirrhosis or liver cancer, with an increased risk of developing several conditions including diabetes, depression and heavy fatigue.

In the camps, people have very limited diagnostic and treatment options. MSF is calling for a joint humanitarian effort to combat the disease among this stateless population already deprived of basic rights and heavily dependent on aid for survival.

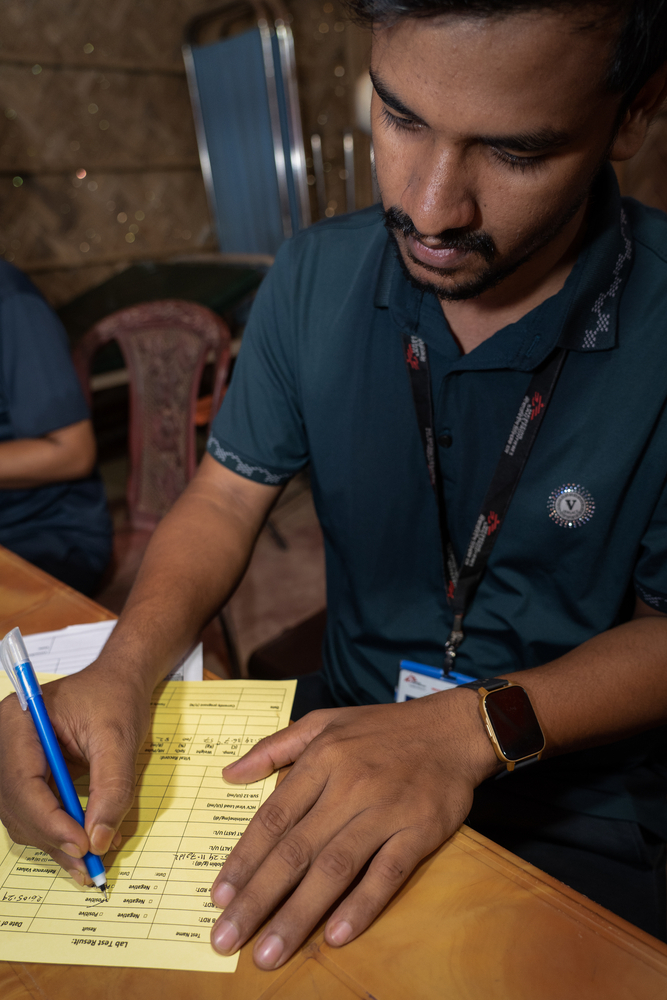

Faced with an influx of hepatitis C patients in the Cox’s Bazar camps over the last few years, Epicentre, MSF’s epidemiology and research centre, carried out a survey of 680 households in seven camps between May and June 2023. The results show that almost a third of the adults in the camps have been exposed to hepatitis C infection at some point in their lives and that 20 per cent have an active hepatitis C infection.

Extrapolating the results of this study to all the camps would suggest that about one in five adults is currently living with a hepatitis C infection – totalling an estimated 86,000 individuals – and requiring treatment to be cured.

Access to diagnosis and treatment is inadequate in many low- and middle-income countries, making this disease a potential public health threat. Yet, direct-acting antiviral drugs can cure over 95 per cent of those infected. In the overcrowded refugee camps of Cox’s Bazar, access to diagnosis and treatment of hepatitis C virus is almost non-existent. MSF has been the sole provider of hepatitis C care there for four years. Yet the need for treatment is extremely high.

Refugees are not legally allowed to work or leave the camps. For those we cannot treat, paying for expensive diagnostic tests and drugs or obtaining appropriate care outside the camps is out of their reach. “Most refugees simply cannot be cured and resort to alternative methods of care, which are not effective and not without risks to their health,” says Sophie Baylac. “We welcome the announcement by the World Health Organization (WHO), the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and Save The Children that 900 hepatitis C patients are to be treated in two health centres in the camps. This is an important step in the right direction. However, a large-scale prevention ‘test and treat’ campaign is needed to effectively limit the transmission of the virus and avoid severe liver complications and deaths. For this, the involvement and determination of those coordinating the humanitarian response in the Cox’s Bazar camps will be required,” she continues.

WHO guidelines and simplified models of care used by MSF in similar contexts have proved efficient to scale up hepatitis C treatment with very good outcomes in humanitarian and low-resource settings. Over the past two years, MSF has also supported the Bangladesh Ministry of Health in drafting national clinical guidelines for the treatment of hepatitis C. MSF stands ready to continue working with national authorities, inter-governmental and non-governmental organisations to implement large-scale prevention and health promotion activities, as well as a mass ‘test and treat’ campaign in all Cox’s Bazar camps in order to limit the virus transmission and treat as many patients as quickly as possible.