In 2002, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) teams opened the first outpatient treatment centre offering free care to people living with HIV in Kinshasa, the capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Twenty years later, while great progress has been achieved in the country, major gaps remain in testing and treatment, causing thousands of preventable deaths each year.

When the doors of our treatment centre opened in May 2002, the situation was critical: more than one million men, women and children were living with HIV in the DRC, but antiretroviral (ARV) treatment was scarce and unaffordable in the country. By the early 2000s, the virus was killing between 50,000 and 200,000 people each year in the DRC, according to UNAIDS

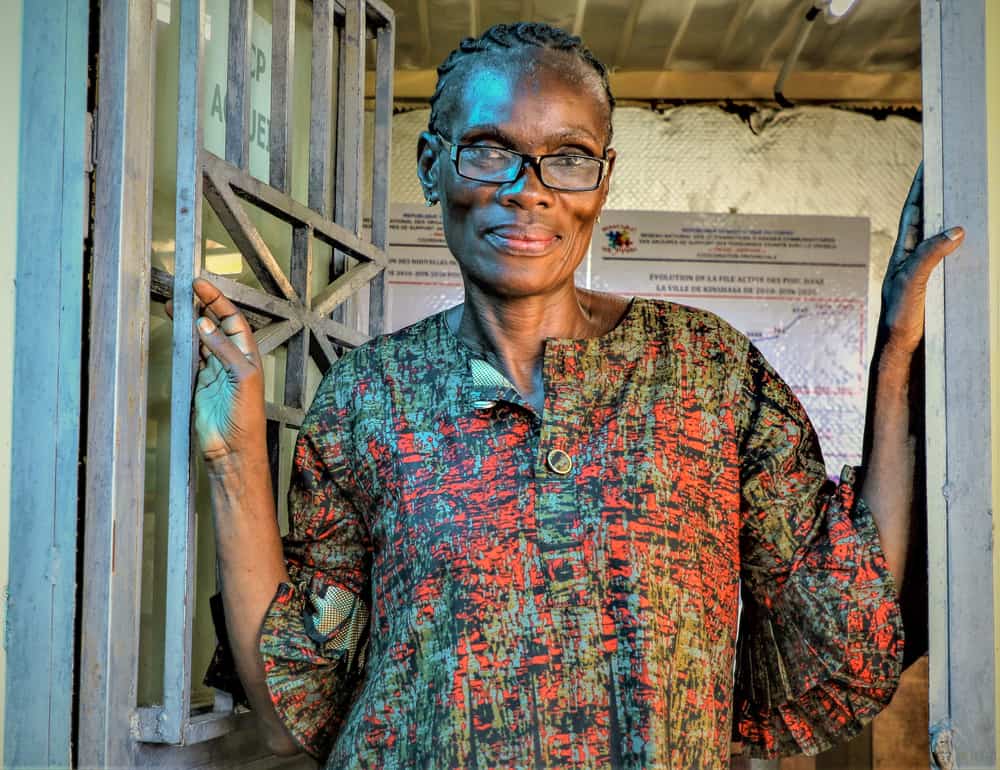

“For many, being infected with HIV was just a death sentence,” says Dr Maria Mashako, MSF’s medical coordinator in the DRC.

“The cost of antiretroviral treatment made it just inaccessible to most patients. Even MSF, in the early months of the centre, did not have ARVs. Our team could only treat symptoms and opportunistic infections. It was very hard.”

MSF driving progress against HIV/AIDS

Being the first health facility to offer free ARVs to patients in Kinshasa, our treatment centre was soon overwhelmed by the large number of people in need of treatment.

“It was just unbearable,” says Dr Mashako, still a young doctor in the facility in the mid-2000s. “Consultations started at dawn and ended at night. There were so many patients.”

To increase access to care and treatment, our teams started supporting other health centres and hospitals in the provision of free screening tests, access to treatment and care. In Kinshasa alone, around 30 health facilities have benefitted from this support over the past two decades.

“It was just unbearable,” says Dr Mashako, still a young doctor in the facility in the mid-2000s. “Consultations started at dawn and ended at night. There were so many patients.”

To increase access to care and treatment, our teams started supporting other health centres and hospitals in the provision of free screening tests, access to treatment and care. In Kinshasa alone, around 30 health facilities have benefitted from this support over the past two decades.

Our teams also set up a pilot model of care that allowed nurses to prescribe treatment and follow up HIV-positive patients. This was a crucial initiative as only a handful of doctors per province were allowed to do so back then.

In 20 years, this support resulted in the training of countless health workers, and nearly 19,000 people receiving free ARV treatment in Kinshasa alone.

“This medical support was of course essential, but not enough,” says Dr Mashako. “We had to limit congestion in health facilities while bringing treatment closer to the patients. That is why we worked with the national network of patients’ associations to launch ARV distribution posts, directly managed by patients.”

Clarisse was one of the driving forces behind the launch of those community-based distribution posts, called “PODI” in the DRC.

“When we launched the first two posts in Kinshasa in 2010, there were less than 20 patients getting their treatment from it,” she recalls. “Today, there are 17 PODIs in eight provinces, and more than 10,000 patients go there to get their medicines.”

The approach proved so successful it was eventually integrated into the national HIV/AIDS plan.

Advanced HIV as a mirror of massive gaps

Great progress has been achieved over the years in the fight against HIV/AIDS in the DRC, and the current situation is just incomparable to that of 2002: access to treatment has been greatly expanded and over the last 10 years the number of new infections has dropped by half.

Yet, our work in the country has been constantly carried out against a backdrop of insufficient national and international resources to win the fight against HIV/AIDS and ensure access to treatment and care for all.

“When we set up an inpatient unit dedicated the provision of care for advanced HIV in 2008, we didn’t think that it would still be full of patients more than a decade later,” says Dr. Mashako. “Over the years, we have doubled its initial bed capacity but we still have to regularly put up tents to accommodate patients. This reflects the immense challenges that remain in the fight against HIV/AIDS in the DRC.”

Since its opening, more than 21,000 people have been admitted in MSF’s advanced HIV care unit in Kinshasa.

“In 2021, UNAIDS still estimated that one-fifth of the 540,000 people living with HIV in the DRC did not have access to treatment and that 14,000 people had died of HIV in the country,” says Dr. Mashako . “As a doctor, I am appalled that so many lives are still being lost for nothing.”

Boosting efforts is urgent and vital

The DRC depends almost exclusively on international donors in the fight against HIV/AIDS. However, their support is insufficient given the scale of the challenges.

“This is a reality that we have been denouncing for years,” says Dr Mashako. “This lack of funding is largely responsible for the lack of free voluntary testing, the lack of training for healthcare providers, chronic shortages of medicines or massive disparities in HIV services between provinces.”

According to the Congolese national AIDS control programme, only three provinces have adequate equipment to measure patients’ viral load, which is key for assessing the evolution of the infection and the effectiveness of treatment.

Setbacks in the fight against HIV/AIDS have even been confirmed in recent years. For instance, activities aimed at reducing mother-to-child transmission of HIV – by testing pregnant women and putting them on treatment – are on the decline.

A quarter of children born to HIV-positive mothers did not have access to paediatric prophylaxis at birth, partly because of paediatric ARV shortages. In addition, two-thirds of children living with HIV are not on ARV treatment.

“HIV will not be defeated in the DRC if stakeholders don’t boost up efforts,” says Dr Mashako. “If I only had one wish, it would be that MSF would not be here in 20 years’ time to treat so many patients with HIV.”