In South Sudan, a fierce battle is being fought against measles. This insidious disease has taken hold across the country and now threatens the lives of the youngest and most vulnerable.

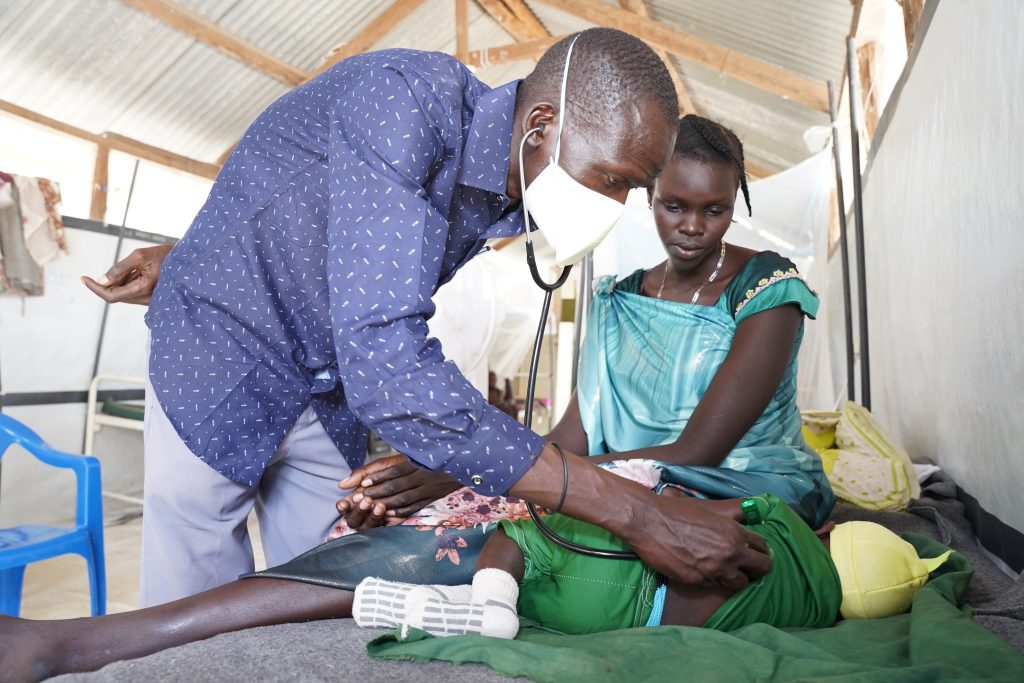

In Lankien, Jonglei state, where Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) manages an 85-bed hospital, 60-year-old Nyandut Nyoach is sitting on the bed next to her four-year-old grandson, Yien, in the isolation ward for patients with measles. She brought Yien to the hospital with typical measles symptoms: high fever, cough and a rash. Yien’s fever was so high that he was having fits (febrile convulsions). Nyandut poured fresh water over his body to lower his temperature before beginning their walk to the hospital.

“We walked for five hours on foot to reach the hospital. This is the closest medical facility that offers hospital care. My nephew and I were alternatively carrying the child while walking here,” Nyandut explains.

In 2022, health authorities declared two devastating outbreaks of this preventable disease. By December, measles had spread to all the states and administrative areas in the country. The outbreak continues into its second year and South Sudan’s fragile healthcare infrastructure is struggling to keep up. Meanwhile, the shadow of malnutrition looms large, tightening its grip on the youngest who are most at risk.

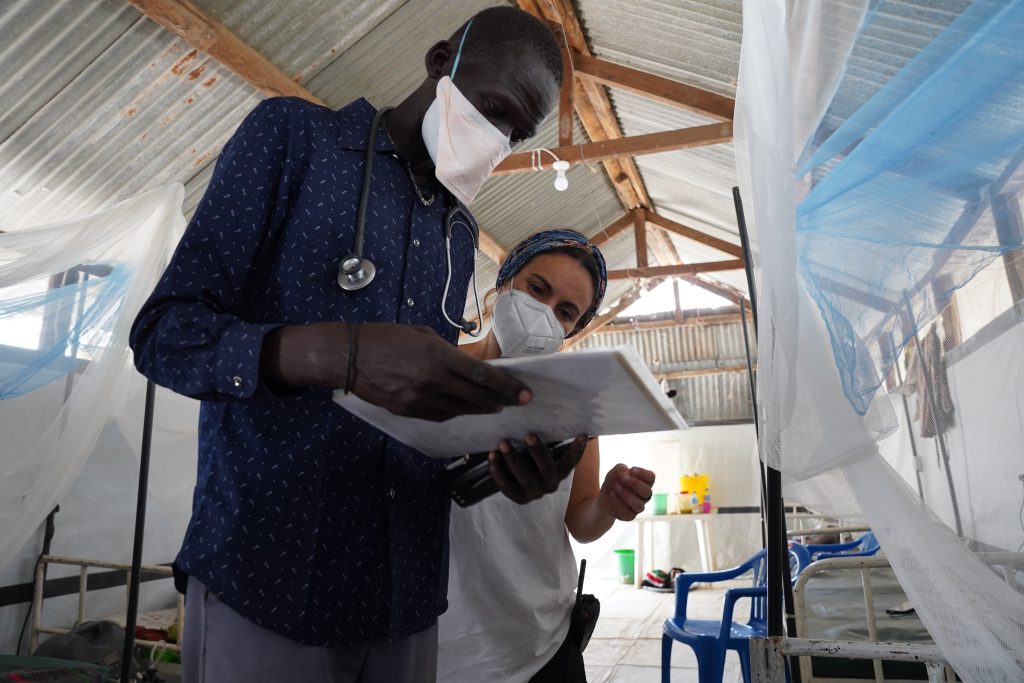

MSF teams have been working tirelessly to treat patients suffering from measles in health facilities across the country, as well as running vaccination campaigns. In 2022, MSF treated more than 1,782 patients with measles and vaccinated more than 170,000 children against the disease.

The ongoing measles outbreaks in the country serve as a stark reminder of the urgent need for increased support to the country’s healthcare system. Additionally, children’s lack of access to essential healthcare aggravates their vulnerability when malnutrition has already compromised their immune systems.

Six-month-old Nhial is also being treated for measles in the isolation ward in Lankien. “There have been other children in the neighborhood suffering from the same sickness. I knew it was measles,” says his mother, Nyareat Nyuon. “A vaccination campaign was recently conducted in our area, but there was nothing prior to that. None of my children were ever vaccinated in the past.”

In the MSF-supported hospital in Aweil in Northern Bahr el Ghazal state, an isolation tent was opened in March 2022 to treat patients with measles. Now, more than a year later it is still open – a highly unusual situation. “Measles outbreaks are usually brought under control within about six months,” explains Mamman Mustapha, MSF head of mission in South Sudan.

South Sudan’s health system is heavily reliant on external support with a limited number of fully functional health facilities. Substantial cutbacks in donor support to health facilities, amid ballooning security and climate-related crises, have battered the public healthcare system in the country.

A nationwide vaccination campaign announced by South Sudan’s government and targeting 2.7 million children is now underway in many areas – including in Aweil where MSF is providing support. In the first three months of 2023 alone, MSF treated 1,073 patients and vaccinated close to 1,600 children against measles across the country.

In addition to increasing vaccination coverage, donor countries and humanitarian groups must continue to work closely with the government to address the underlying causes of the healthcare crisis in the country to ultimately save lives and improve people’s long-term health.