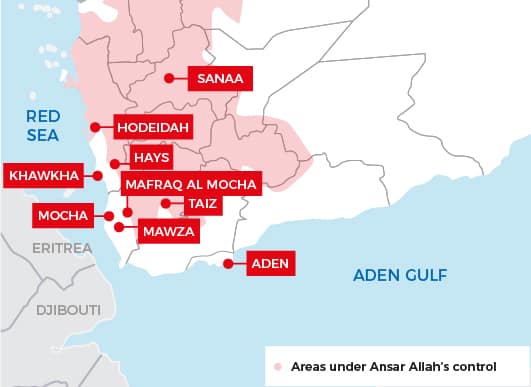

In early 2018, fighting intensified along the frontline between the cities of Taïz and Hodeidah by Ansar Allah troops and forces supported by the Saudi and Emirati-led coalition. The coalition-backed forces advanced on the strategic port of Hodeidah, on the Red Sea, before launching an attack on the city on 13 June 2018.

In an effort to prevent the advance of the coalition’s ground troops, thousands of mines and improvised explosive devices were planted across the region’s roads and fields. The principal victims of these lethal hazards have been civilians, many of whom have been killed or maimed for life after unwittingly stepping on an explosive device.

MSF set up a hospital in the city of Mocha, in Taïz governorate, in August 2018, where its teams perform emergency surgery on people injured by mines – one-third of them are children. MSF urges the authorities as well as specialist organisations to step up mine clearance operations to reduce the number of people killed and injured by explosive devices in civilian areas.

At the MSF hospital in Mocha, December 2018, a bell sounds in the yard of the tented hospital signalling the arrival of yet more patients.

A pick-up truck armed with a rocket launcher screeches to a halt and unloads four patients in front of the emergency room. Two are children covered with hastily applied bandages; the other two are already dead. Just a few hours earlier they had been with family members in fields in Mawza, some 30 km away, when someone stepped on a mine.

Like them, 14-year-old Nasser was wounded when a mine exploded. A scar on his left-hand shows where his thumb was amputated after he was hit by a bullet some years ago. Standing up on his crutches for the first time, he tries to get his balance. Nasser stepped on the mine on 7 December while he, his uncle and cousin were watching over the family’s sheep in a field in Mafraq Al Mocha in Taïz governorate.

Later that day, Nasser was operated on in MSF’s surgical hospital 50 km away in Mocha. Part of his right leg was amputated below the knee. With a thumb missing, it’s hard for him to use the crutches. MSF physiotherapist Faroukh helps him to take a few steps between the 10 beds in one of the hospital’s three inpatient wards. “The bone was completely shattered so there was nothing to left to save,” says Faroukh.

Since the accident, Nasser’s father, Mohammed, has been very apprehensive about walking in the fields around Mafraq Al Mocha. “We know mines have been planted around the town, but the problem is we don’t know exactly where,” he says. With only a handful of signs indicating the presence of mines and only a few red-painted stones showing where it’s safe to walk, every day a muffled bang signals that yet another explosive device has been triggered.

Punished – not once, but twice

Before the war, the area between Mocha and the frontline was agricultural. Since the fighting started, towns and villages near the combat zones – such as Hays and Mafraq Al Mocha, where MSF provides support to advanced medical posts – have seen many of their inhabitants flee. The surrounding fields have been mined to prevent the advance of military troops, making them impossible to cultivate and depriving the local population of their livelihood.

A 45-minute drive from Mocha, Mawza district has seen its population halve. “People who live here are punished – not once, but twice. The mines not only blow up their children but also prevent them from cultivating their fields. They lose their source of income as well as food for their families,” says Claire Ha-Duong, MSF’s head of mission in Yemen.

Between August and December 2018, MSF’s teams in Mocha admitted and treated more than 150 people wounded by mines, improvised explosive devices and unexploded ordnance – one-third of them children, who had been playing in fields. Disabled for life, they face an uncertain future.

By creating generations of maimed people, mines have far-reaching repercussions – not only for individual families but for society as a whole, as their victims are likely to be more dependent on others at the same time as being more socially isolated. The mines also prevent people in agricultural areas from cultivating their fields, which takes a heavy toll on the families who rely on the income.

Inadequate mine clearance

Thousands upon thousands of explosive devices will endanger the lives of people in Yemen for decades to come. UK-based organisation Conflict Armament Research pointed in a recent report to Ansar Allah’s large-scale mass-production of mines and improvised explosive devices, as well as its use of anti-personnel, vehicle and naval mines. According to the Yemen Executive Mine Action Centre, the Yemeni army cleared 300,000 mines between 2016 and 2018.

Managed almost exclusively by the military, mine clearance is focused on roads and strategic infrastructure, with little heed paid to civilian areas. “Specialist mine clearance organisations and the authorities must step up their efforts to demine the region in order to reduce the number of victims,” says MSF head of mission Claire Ha-Duong.

As well as demining strategic areas for military, civilian areas urgently need to be cleared of all types of mines and explosive devices – not only from places where people live, but also from agricultural land so that people can access their fields again in safety.

Medical wasteland

Not a day goes by without war-wounded people like Ali and Omar arriving at MSF’s hospital in Mocha from the frontlines between Taïz and Hodeidah. Aden, where MSF opened a specialist trauma hospital in 2012, is 450 km from Hodeidah. Although there is medical care available in Aden, most Yemenis don’t have the money to pay for treatment or the transport to travel there.

It takes six to eight hours to drive to Aden from Hodeidah. The area between the two cities has become a medical wasteland for the people who live there. MSF’s hospital in Mocha is the only facility in the region with an operating theatre and the capacity to perform surgery.

“The coastal region between Hodeidah and Aden is rural and extremely poor. People have no access to medical treatment and our hospital is the only place they can go when they need surgery,” says Husni Abdallah, a nurse in the operating theatre. “They’re essentially patients with war wounds. Some don’t manage to get to Mocha in time and die of wounds that could have been treated. Or they’re pregnant women who die during labour due to a lack of adequate medical care.”

“The war-wounded often get to Mocha very late and many are in a critical condition. They contract infections because on the frontline they aren’t always stabilised as well as they should be. Mines cause particularly severe injuries, so we see complex fractures that are difficult to operate on. Patients often have to have amputations and then require months and months of rehabilitation,” says Husni Abdallah.

Injured at the same time as his nephew, Nasser’s uncle had fragments from the exploding mine in his eyes. He was taken straight to MSF’s hospital in Aden, 270 km from Mocha, for the specialist treatment he needed. Since MSF opened its hospital in Mocha, its staff have provided more than 2,000 emergency room consultations and performed around 1,000 surgical procedures.