South Sudan faces a profound but often invisible mental health crisis. Decades of conflict, displacement, and poverty have left deep psychological scars. Yet, with only a handful of trained professionals and virtually no specialized facilities, individuals in crisis are often stigmatized, neglected, or treated as criminals.

33-year-old Samat Nyuk’s experience reflects the reality faced by many. He was given a phone to keep but sold it to ease his financial difficulties. He was taken by the police, not for selling the phone though, but for another matter.

The consequences spiraled rapidly, not from the law, but from a severe and sudden mental health crisis that distorted his reality and isolated him from the world he knew.

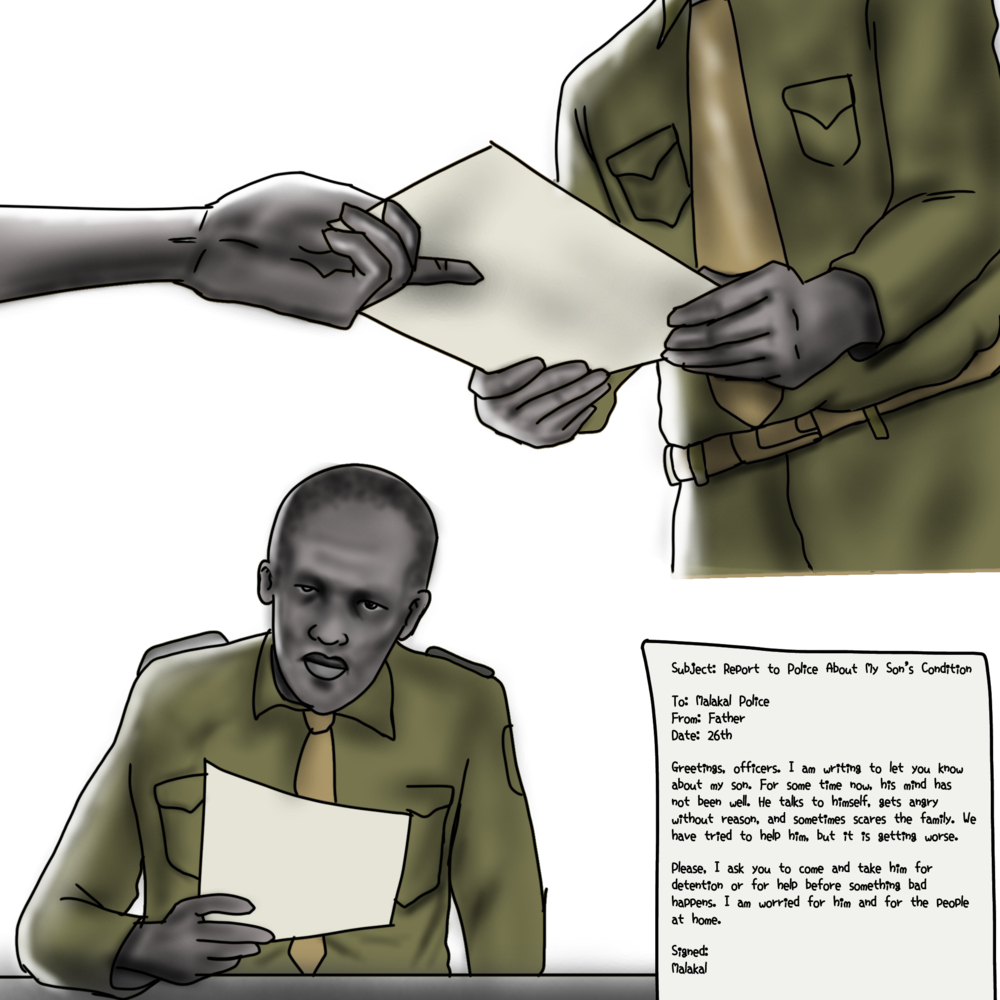

In Malakal, Upper Nile State, families with nowhere to turn sometimes feel their only option is to hand over relatives to the police.

“That Moment Broke Me”

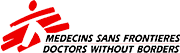

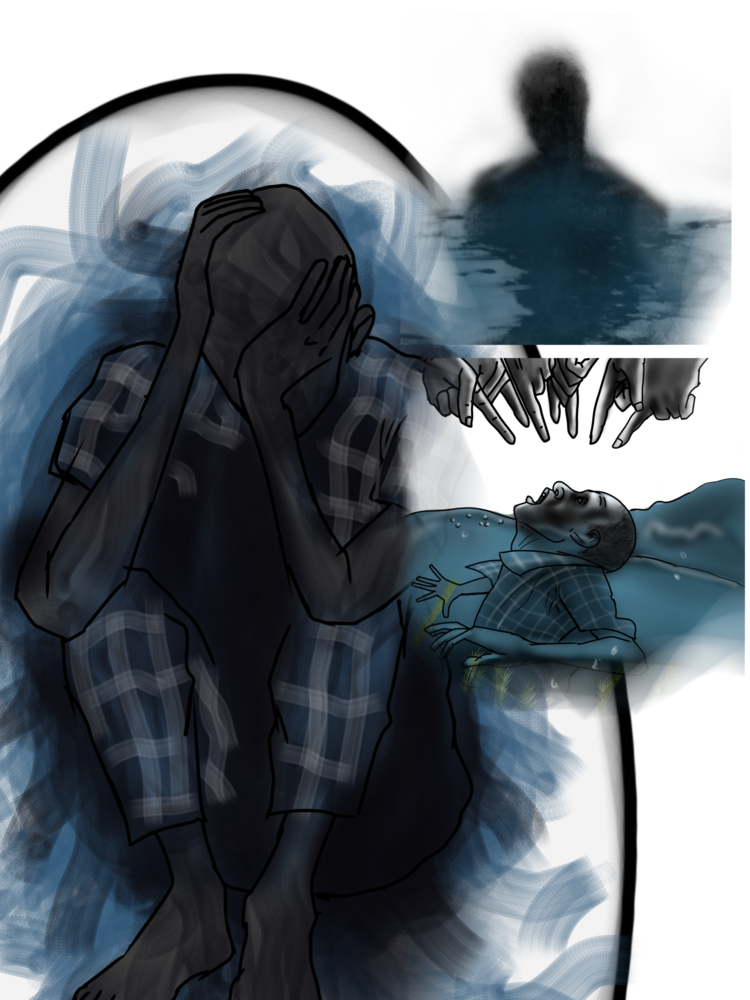

Samat’s experience reflects this harsh reality. After a period of personal hardship, he began hearing voices and losing touch with reality.

His mind created vivid, frightening illusions. What he perceived as a life-threatening struggle was, in reality, happening on a dry road, demonstrating the powerful and deceptive nature of his illness. Following the voices, Samat Nyuk walked away from home. He felt as if he was crossing a river where the water reached his neck, and he saw fingers pointing at him and heard voices telling him to drown.

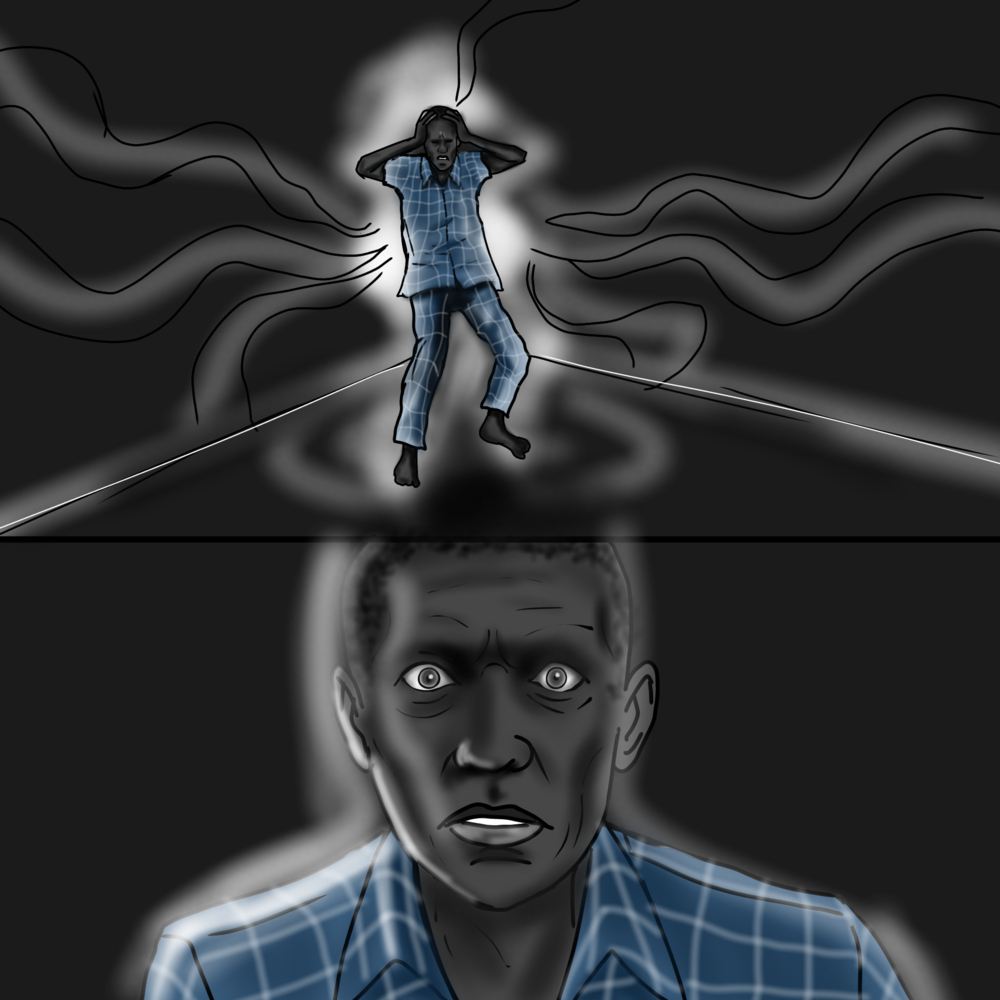

A friend recognized his suffering and sought traditional help. A local elder provided a root, which offered a brief moment of calm, but it was not enough to silence the voices for long.

Fearing for his son’s safety and that of the family, Samat’s father, Nyuk, took the drastic step of reporting his condition to the local police. He formally wrote a request that they take Samat for detention or help, a document that would alter Samat’s path

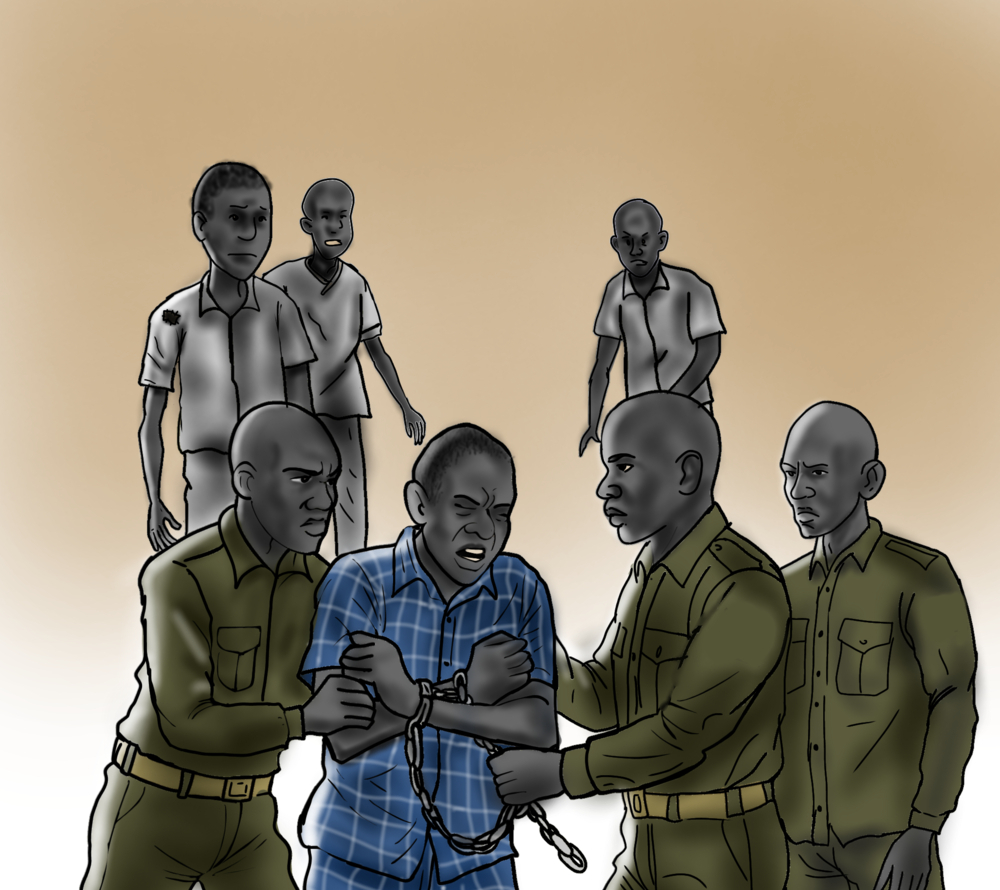

The police response was not medical, but custodial. Since there was no treatment facility for psychiatric patients, the only alternative was a painful one. Samat was restrained in June 2025 and taken to Malakal Central Prison, where individuals with mental health conditions are often isolated in cells.

Samat was placed in a small cell in the prison’s isolated section for the mentally ill. His existence was reduced to a bare, monotonous, and profoundly lonely struggle for survival.

He was put behind bars in a small cell, where mentally ill prisoners are isolated. Every day was the same. One meal, only dry maize meal served daily at 3:00 pm. No soup, no mosquito net, no bed, nothing warm at night. His family never came to see him. His brother-in-law was the only one left by his father to visit him. He was completely alone.

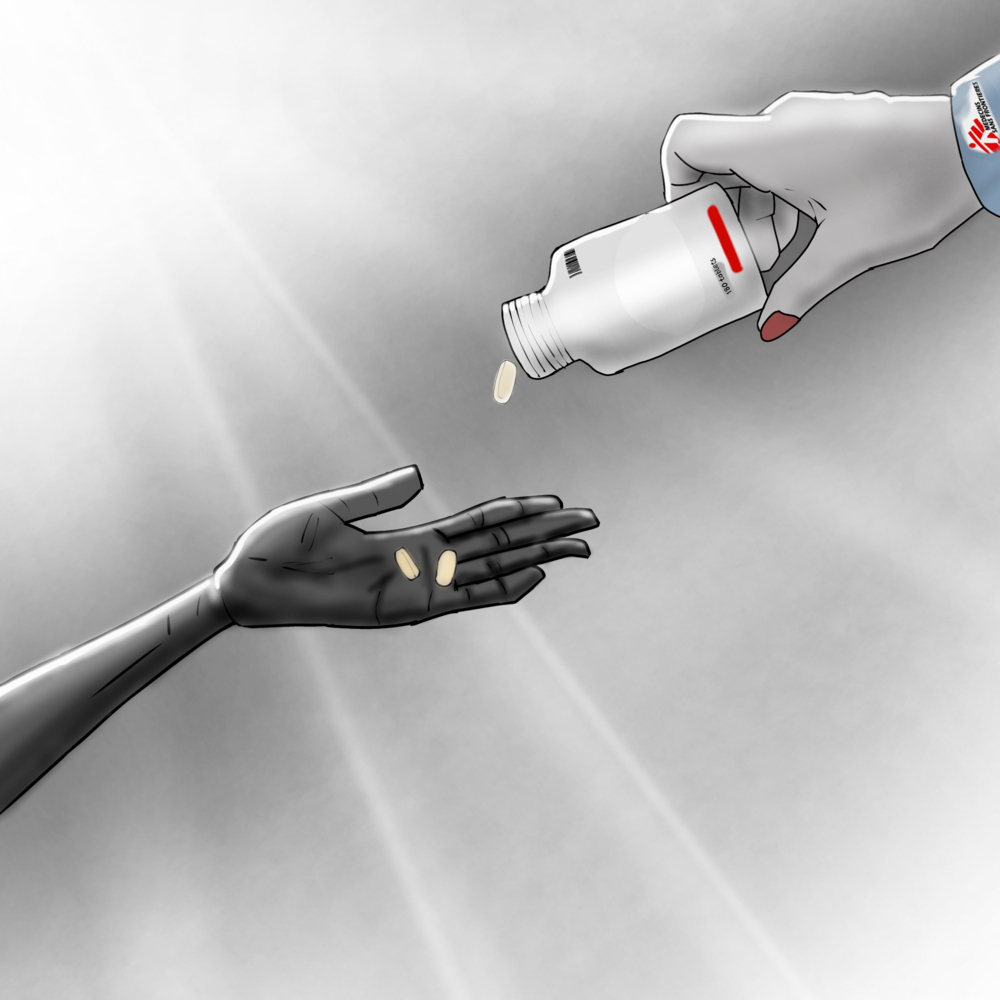

After days of this isolation, a mental health team from Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) arrived at the prison. Their approach was different: they offered gentle words, a listening ear, and, crucially, medicine for a psychiatric condition he was suffering from.

The MSF medical team spoke gently to the prisoners, listened, and brought medicine for them. For the first time, they felt seen “not as prisoners, but as patients.”

The MSF team provided psychiatric medication and consistent counselling. Samat began a daily treatment regimen. The medicine helped, but the prison conditions made recovery a struggle. The lack of food weakened him, making the side effects of the medication hard to bear.

Despite the hardship, the effectiveness of the treatment was undeniable. Samat began to feel inner peace and a renewed hope for the future, the hope of recovery and eventual freedom.

After three months of imprisonment and two months of MSF care, Samat was released from Malakal Central Prison. He was free to reclaim his life and his autonomy in September 2025.

Today, Samat is regaining his strength and autonomy. The simple choices of freedom are profound.

Samat’s strength comes from his freedom and the continued support of his treatment. He is now focused on the practical steps of rebuilding his life, one day at a time.

Samat’s story is not unique. MSF teams in Malakal have seen children as young as 14 detained for untreated mental health conditions or minor infractions.

MSF’s work has demonstrated that with medication, counselling, and consistent follow-up, recovery is possible. But progress is fragile without a functioning health system and social support.

As Samat himself insists, the path forward is clear: “Prisons are no place for people with mental health conditions. What we need are hospitals, places where there is treatment, food, and hope for recovery.”

-

Related:

- mental health

- World Mental Health Day