MSF teams in the Palestinian enclave are coping with the arduous task of replacing the centimetres of bones pulverised by Israeli bullets in the bodies of protesters. The limited resources available on site, however, make it impossible to provide a viable solution for many of them – this is why referrals to hospitals abroad are a necessary part of the equation.

Two centimetres doesn’t sound like much. When it comes to your leg, though, a missing two centimetres of bone leaves a big hole – especially when the cause is a bullet turning and smashing its way through your body. That much was evident at al-Awda hospital in Jabalia, in northern Gaza, as MSF surgeons opened the shin of Yousri*. He had been shot by the Israeli army during protests in July 2018, and the bullet had left a big chunk of missing bone just underneath the knee. It was the job of the surgeons to take bone from Yousri’s hip to fill that gap and help him walk again.

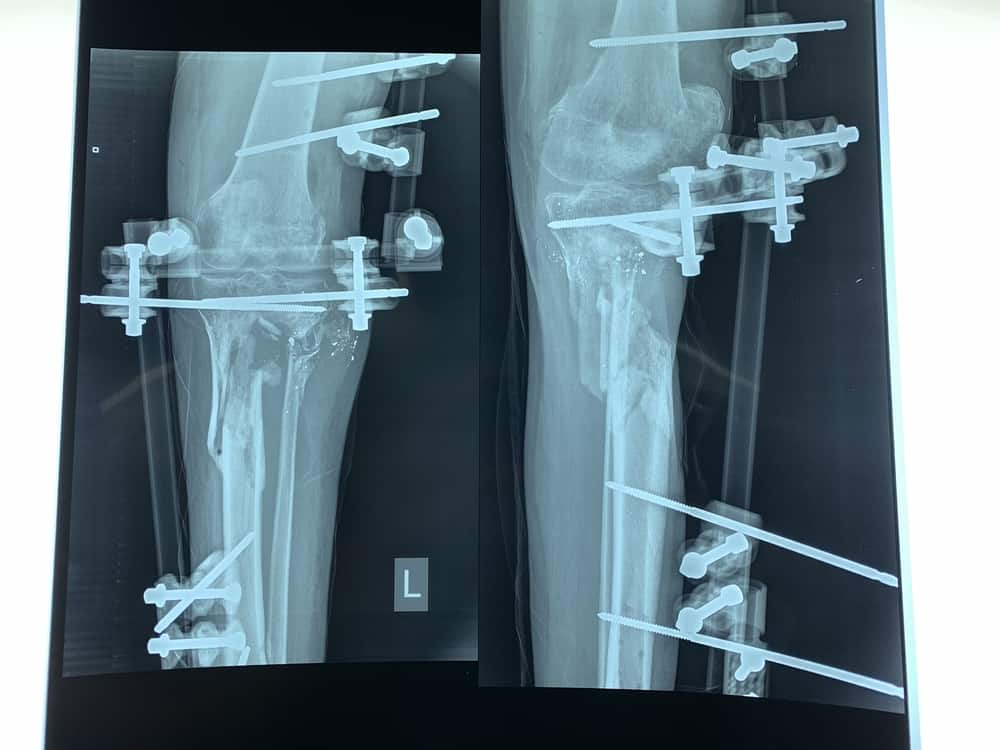

Orthopaedic surgery is a lesson in contrast between precision and power: Dr Hiroko Murakami, an MSF surgeon from Japan, first carefully cut through the skin with her scalpel, delicately exposing the bone. She then used a hammer and chisel to chip off a sizeable bit of hip, and it was this that would be carefully shaped and placed in Yousri’s leg. “It will take at least two or three months for the bone to fuse,” Dr Murakami said, “and could be longer. After that time we will see if everything is ok, and if it is, then we can remove the external fixator and the patient can start physiotherapy. So it’s still going to take him a long time to recover.”

Unfortunately, as ghastly as the gap left by the bullet in Yousri’s bone was, his case was relatively simple. In protests held along the fence that separates Gaza from Israel since March 30th, 6,174 people have been injured by live bullets fired by the Israeli army. Nearly 90% of those were injured in the lower limbs. MSF has provided care for around half of the wounded after their initial treatment in local hospitals, and the wounds we have observed have been unusually severe. Patients have complex open fractures – where the bone is exposed to the air – in half the cases and severe tissue and nerve damage in most of the rest. Many patients are missing huge parts of their leg bones: if two centimetres leaves such a big hole, just imagine ten.

When the gap is bigger, like the six centimetres missing in the shin of Salim*, then it is not possible to do a bone graft straight away. Dr Mohammed Obaid, an MSF surgeon from Gaza, explained that this was a complicated case. “There was a raw area: the patient had an open wound, no skin, so the plastic surgeon made a covering of muscle from another part of the leg four weeks ago. Now we will open the wound again, clean it, and put bone cement inside.” This cement is putty with a pungent smell close to that of petrol. At first malleable, the surgeons massage it into the bone gap and mould it into the required shape. The cement quickly hardens and, over six to eight weeks, prepares the area to receive a bone graft. “When we are sure that there is no infection in the bone, and that the flap we have covered the wound with is good then we can reopen the area, take the cement out, and put the bone in,” Dr Obaid said.

For the most serious patients, however, the treatment that they need is very difficult to obtain in Gaza, a crowded piece of land that has been blockaded for the past ten years, and isolated for a lot longer. Therefore MSF is also transferring patients from Gaza to its reconstructive surgery hospital in Amman, Jordan. This is a complicated process that requires permission to travel from many sets of different authorities: permission that is often denied. However, MSF was recently able to send its first patient injured in the protests – Eyad, 22 – out of the Palestinian enclave. He had been shot on May 14 – the bloodiest day of the protests – and requires a bone graft and reconstructive surgery to repair the damage to his leg. The health system in Gaza is currently only able to offer this type of surgery to very few patients.

“One-day last week I was tired and depressed because treatment for my leg seemed so far away,” Eyad said. “However, in the evening of the same day MSF rang me and said, ‘Eyad, on Thursday, you will travel.’ Since that time happiness has risen inside me, not just for me, but for my mother, my brothers, my family and all my loved ones. I can’t believe it.” Now in hospital in Amman, he has begun the long process of having his leg bones reconstructed, a series of operations that will hopefully return him to normal life.

Many other patients remain in dire need of continued medical attention, however, with the passing of time multiplying the risk of infection and the chance that some patients will lose their limbs. MSF is still taking care of 900 people in Gaza with gunshot wounds. Although that number is smaller than at the protests’ peak, we are doing more operations now than ever: 302 in December, as compared to 109 in April, which shows how the surgical requirements of the most seriously injured develop over time.

The increasingly serious and urgent medical risks for those wounded in protests since March are why MSF is both expanding its capacities in Gaza and trying to send more patients for treatment abroad. . The needs of these patients, however, are overwhelming both MSF and other healthcare actors in Gaza, leaving much still to be done if hundreds of patients are not to find themselves with life-changing consequences.

*Names have been changed.