The second wave of COVID-19 hit India at the end of March 2021. In April, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) sent doctors and nurses to work in Mumbai’s Jumbo Hospital that had a capacity for 2,000 patients. Teams also adapted regular medical projects to support patients receiving care for HIV (in Manipur), tuberculosis (TB) (in Mumbai), Sexual and Gender-Based Violence (in Delhi) and mental health counselling (in Jammu & Kashmir) while the country was locked down and hospitals were overwhelmed.

However, with a relatively small presence in India, MSF was not best placed to react to the initial devastating impact of COVID-19 in the major cities. MSF teams started looking to see where they could meet health needs outside of Delhi and Mumbai. In June 2021, MSF launched a small emergency response in Manipur to provide COVID-19 surge support in the city and its surroundings, following a call for support from the Ministry of Health in India.

LAUNCHING AN EMERGENCY RESPONSE

Manipur sits tucked in the northeast corner of India. Its capital, Imphal, is home to almost half of the state’s urban population, with numerous dialects, beliefs and ethnic groups in its territory. As the second COVID-19 wave swept through India, Manipur felt the effects too.

The MSF response aimed to assist those not able to access healthcare facilities due to cost, distance, stigma, and other barriers.

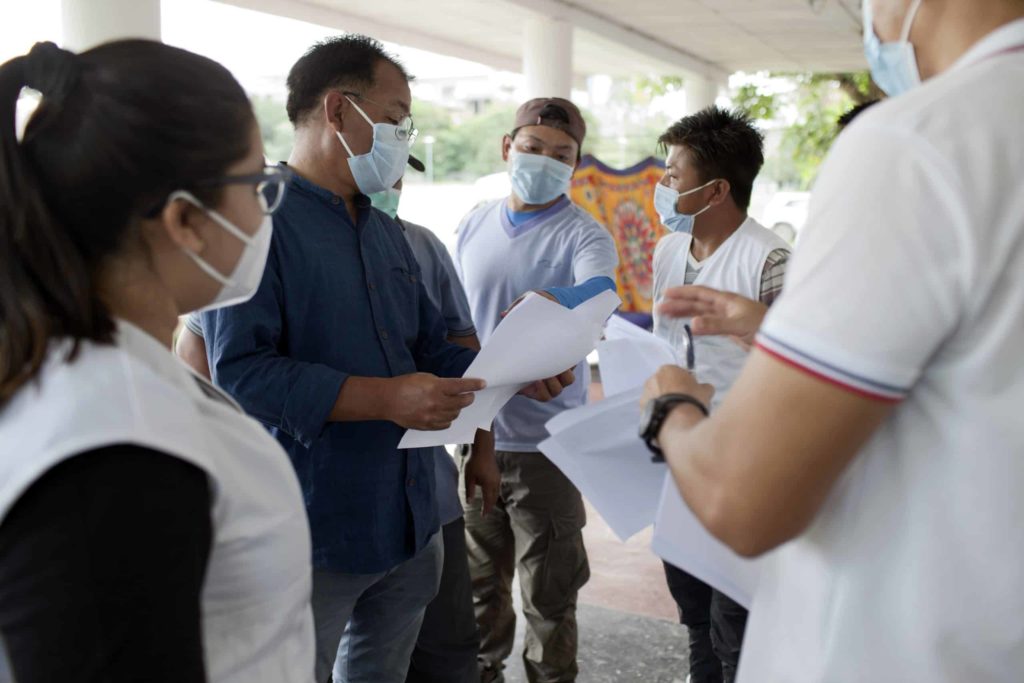

In order to reach people, cut off from the city’s health services and isolating at home, MSF formed mobile response teams comprised of doctors, health workers, and drivers who travelled several kilometers across the Imphal valley every day to visit people isolating with confirmed or suspected COVID-19.

With more than thirty different dialects in this culturally and ethnically diverse area, community health workers with different language skills and local knowledge play a major part in ensuring that MSF teams reach vulnerable patients from different backgrounds.

“We quickly realized that it was important to expand the catchment areas of MSF’s mobile response teams to the more rural areas outside of Imphal – where access to healthcare is more challenging,” says Luca Pigozzi, MSF’s Medical Team Leader during the emergency response in Imphal.

“We managed to expand our outreach and mobile response teams to neighbouring districts of Thoubal and Bishnupur and to establish collaboration with district hospitals and COVID care centres.”

Launching an emergency response during a global pandemic presented MSF teams with enormous challenges, but for 26-year-old doctor Ashwin Krishnamoorty, working in a Mobile Response Team with MSF provided an opportunity to connect with patients and provide quality care free of charge.

“Working as part of a mobile response team, I have got a glimpse into the culture, understood better the overall healthcare situation here, and got to know the perceptions people have about COVID-19,” Dr Krishnamoorty said.

MSF mobile response teams visit as many as 11 households in a single day.

They provide in-person examinations, hygiene kits containing items like soap for handwashing, and share health education messages around good hygiene and infection prevention to minimize the risk of COVID-19 spreading.

As a core part of the intervention, MSF set up a 42-bed High Dependency Unit (HDU) for COVID patients at Little Flower School, a private convent school near Imphal airport.

It received patients suffering from severe COVID and provided high flow oxygen and non-invasive ventilation. Some patients were referred directly by MSF’s mobile response teams.

“After we started working outside of Imphal, we noticed immediately that our HDU was filling with people who came from areas with more vulnerabilities,” says Luca.

Dr Ashwin Krishnamoorty recalls an 80-year-old patient who was admitted to the HDU.

He recovered and before discharge, he prayed for the wellbeing of the doctors and thanked them for taking care of him, with his hands joined and tears in his eyes.

“It somehow made me sit up and notice the patients, and the impact our work has on them.”

NURSES AND COMMUNITY HEALTH WORKERS

The contribution of local nurses and community health workers has been invaluable. By acting as translators, they enabled doctors to communicate effectively with their patients.

Doctor Reanna Irani is grateful to them and recalls – “One nurse – I was very impressed with her. She is from Imphal. When a patient is upset, distressed or disoriented – she pats them gently on the head or hand and plays calming music for them.

I found it so kind and important for patients who are in great distress – they worry about their breathing, pain, they are not sure what will happen.”

Some people, who don’t have the space to isolate themselves at home, must move away from loved ones to stay in community centres until their isolation period is over.

The high demand for beds in hospitals has meant that some hospitals only accept patients referred by a medical doctor. MSF’s mobile teams are able to provide these referrals when they meet people in need of additional care during home visits.

MSF wrapped up its emergency response in the Imphal valley in mid-October 2021 after no new patient admissions and an apparent decrease in the incidence of COVID-19.

During the intervention, MSF was able to provide surge capacity to a health system overwhelmed with severe and critical COVID-19 cases.

Vulnerable and remote populations outside Imphal could access treatment of severe COVID and a referral pathway to treatment of critical COVID.

High-risk patients were identified early and referred to the appropriate level of care.

As much as possible MSF tried to ensure that in the relationship between the healthcare provider and patient, the person behind the patient was recognised.

Beyond that, the relationship between MSF and the communities it served was also of crucial importance.

The 42-bed High Dependency Unit (HDU) that was set up admitted a total of 265 patients with bed occupancy rates reaching 97% during peak periods in July.

Patients with severe COVID received evidence-based quality clinical care.

The MSF mobile medical teams that visited state run isolation centers in rural areas and provided care to patients in their own homes, carried out more than 600 patient examinations. They referred (and transported) 222 patients to the MSF high dependency unit. In addition, around 1,200 patients with mild to moderate COVID were treated in their own homes.

The MSF outreach team made up of doctors and nurses, visited 54 villages in remote and rural areas with a high burden of COVID, and distributed 660 hygiene kits. Engagement with the community was essential to better understand local knowledge and perceptions about COVID. By establishing a feedback loop with communities, MSF could try to find ways to increase access to testing and treatment.

-

Related:

- COVID-19

- COVID-19 in India

- India

- Manipur