At the end of 2017, horrific images of migrants sold as mere commodities in Libya were travelling around the world. This sparked a global outcry and pushed many leaders, in Europe, in Africa, in Libya, to promise measures to protect refugees and migrants from abuse and slavery-like conditions.

However, two years later, nothing has really changed. Working to assist migrants and refugees in Libya since 2017, MSF teams have been witnessing the desperate situation of thousands of people, condemned to languish in detention centres or left to survive on their own outside, trapped in an endless cycle of violence.

Along the roads of Libya’s cities, many migrants wait each day for the opportunity to get a few hours of work. These ‘daily workers’ hope that a potential employer will spot them. The process is simple: vehicles stop by the side of the road to recruit a labour force.

Other migrants regularly work for the same employer, sometimes living at their workplace. A salary is not always guaranteed. It varies greatly depending on the situation; in Misrata, migrants can earn up to 2,000 Libyan dinars (around €1,280) a month. A sum that remains attractive for many compared to the economic prospects in their country of origin.

For decades, oil-rich Libya has been a destination country for migrants from neighbouring Niger and other sub-Saharan countries seeking opportunities to work in construction, agriculture and the services industry. The International Organisation for Migrations (IOM) estimates there are between 700,000 and 1,000,000 migrants in the country.

Since the uprising in 2011, the fall of Gaddafi and the civil war that followed, the situation for migrants working in Libya has become far more difficult. The country is riven with armed conflict, as rival governments and militias fight for control, and public services have collapsed. The majority of migrants do not have residence permits or other documentation, which puts them at risk of arrest and arbitrary detention. Whether they see Libya as a stop on their journey or their destination, all become targets on migratory routes made more dangerous, costly and fragmented.

While Colonel Gaddafi was in power, the EU and Italy both struck contentious deals with Libya, providing funding in return for a promise to keep unwanted migrants and refugees away from Europe. The Libyan leader warned during a visit to Italy in 2010 that Europe could “turn into Africa” unless the EU paid Libya €5 billion a year to seal its Mediterranean coast.

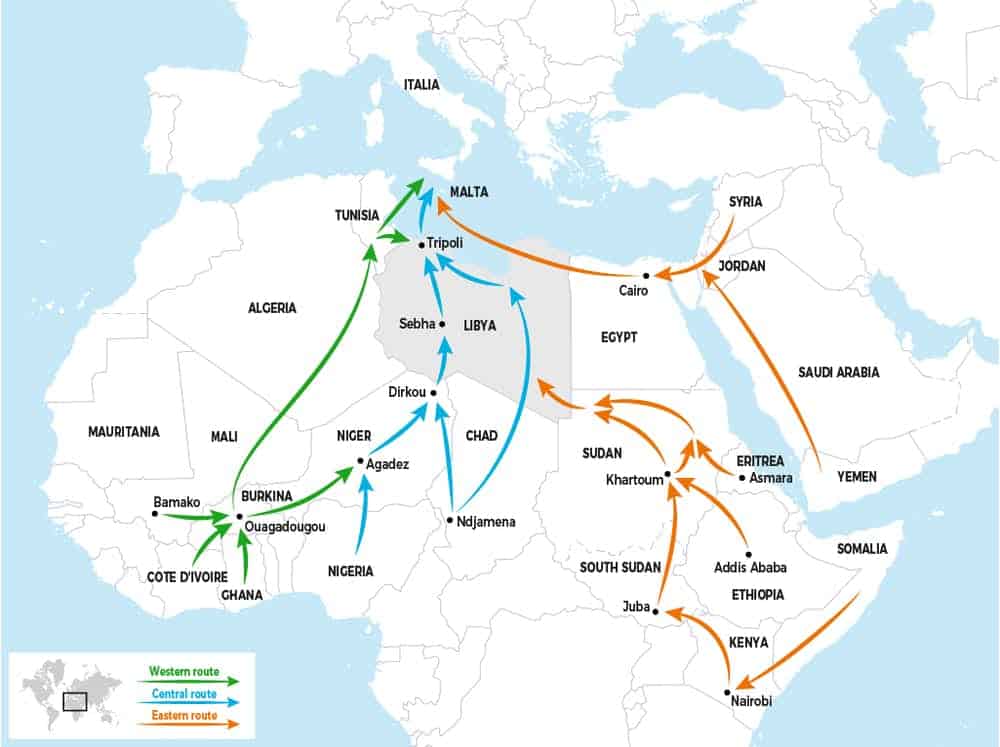

The chaos that set in after the second Libyan civil war began in 2014 has provided a fertile ground for a dark economy to grow, based on plundering resources and illicit activities such as trafficking in oil, weapons and people. Libya has turned into the major gateway to Europe for those fleeing repression, conflict and poverty in the region.

To stem the flow of new arrivals, European states have implemented brutal containment and push-back policies. They have dismantled search and rescue capacities at sea, while sponsoring the Libyan coastguard to intercept refugees and migrants in international waters and forcibly return them to Libya, in violation of international law, and cutting deals with various actors known for their links with criminal and smuggling networks. As a result, human trafficking, abduction, detention and extortion of migrants and refugees continued to flourish in Libya while people’s chances of dying in a bid to cross from Libya to Europe have only increased.

This situation was documented and denounced by MSF and by observers from the UN and other organisations.

Part 2 – The CNN effect: where are we two years later?

In November 2017, the level of violence against refugees and migrants reduced to mere commodities in Libya was exposed in a CNN report. This triggered a global outcry, with thousands of people across Africa, Europe and beyond shocked by the horror of human trafficking and the extent of torture and slavery reported in Libya.

Many international leaders, including European policymakers, condemned the situation in Libya. The Libyan Government of National Accord (GNA) – the UN-recognised authority in the country – said it would launch a formal investigation to look into CNN’s allegations, described by a GNA Minister as “inhumane and contrary to the culture and heritage of the Libyan people”.

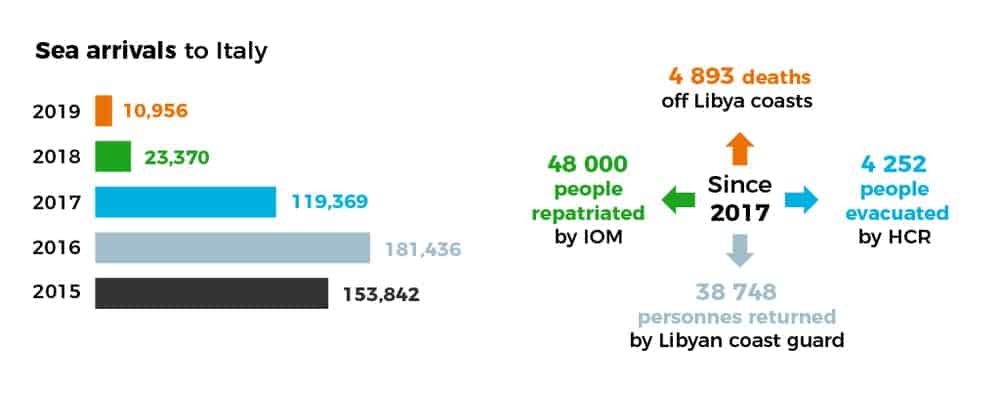

The EU, together with the African Union and the UN, created a taskforce to accelerate the IOM’s assisted voluntary return of migrants and to set up humanitarian evacuations of refugees by the UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR). UNHCR began evacuating refugees to a transit centre in Niamey, Niger, in December 2017.

From there they could then have their full refugee status determined and await solutions, such as resettlement in a third country. Increased funding was also provided to UNHCR and IOM, the two main EU partners, to deliver assistance and protection to refugees and migrants in Libya.

However, two years after this global outcry, the thousands of people trapped in Libya, subjected to horrific violence with no hope of freedom, have fallen from the public eye. Refugees and migrants continue to be traded like cargo, passing from trafficker to trafficker.

European taxpayers’ money is being used to contain people in inhumane conditions to prevent them from exercising in Europe their fundamental right to seek asylum. They are held indefinitely in squalid prisons without judicial review.

Those able to return to their country of origin resign themselves to do so with the help of the IOM. This has been the case for nearly 48,000 migrants since 2017. But those that cannot return to their country of origin find themselves stuck in danger.

The mechanism for evacuating refugees from Libya to transit countries is currently working at a snail’s pace due to lengthy procedures using restrictive criteria and the overall lack of places provided by safe countries. Each stage of the journey becomes a bottleneck quickly clogged with survivors, while the priority of the European states remains to welcome as few as possible.

The UNHCR has evacuated nearly 3,000 refugees from Libya to a transit centre in Niamey, Niger since late 2017. A similar mechanism has been set up in Romania, and another was launched in September 2019 in Rwanda. Apart from Italy, no state has organised humanitarian evacuation flights for refugees directly from Libya.

From January to November 2019:

BEING CAUGHT TRYING TO FLEE

With roughly only 2,000 places available each year for the resettlement of refugees from Libya to a third country, UNHCR is currently prioritising women, families and young children for evacuation. A young, single man that fled political persecution in his home country and is now being detained in Libya has almost no chance of benefiting from it.

In contrast to this limited evacuation system, the European state-sponsored system of forced return to Libya is working at full capacity. From January to November 2019, 2,142 refugees were evacuated out of Libya by UNHCR, but nearly 9,000 people were forcibly returned there after being caught attempting to flee by sea.

Even the severe deterioration of the situation in Libya, following the latest escalation of the armed conflict between the GNA and the Libyan National Army (LNA) in April 2019, has not affected the European policy of forced return and containment in Libya.

More than 200 civilians have been killed in Libya since April. Indiscriminate shelling, gunfire and airstrikes continue to regularly hit Tripoli and surrounding areas. Accordingly to the UN Mission in Libya (UNSMIL), there have been over 1,000 drone strikes, the majority in support of LNA forces, since April.

On 3 July, an airstrike on the Tajoura detention centre in the eastern suburbs of Tripoli killed 53 people trapped inside and injured 130. This tragedy was entirely preventable and occurred after numerous MSF calls for immediate evacuation of refugees and migrants caught up in the conflict.

There are between 3,000 and 5,000 migrants and refugees held in ‘official’ detention centres, nominally under the authority of the Libyan Ministry of the Interior based in Tripoli and its agency in charge of combating illegal immigration, the DCIM. The majority of these are registered with UNHCR and are seeking asylum.

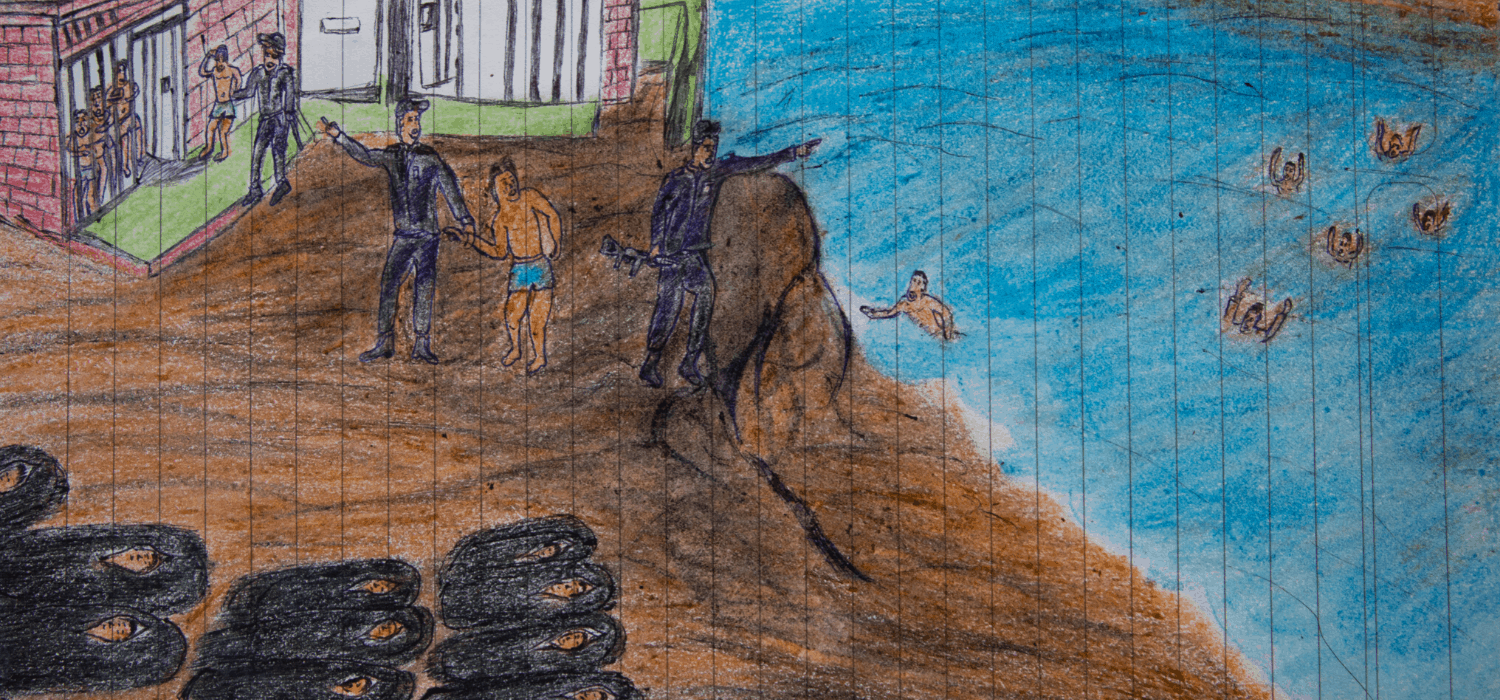

An unknown number of people are being held captive across the country in clandestine prisons and warehouses by smugglers and traffickers, who use torture and abuse to extort money from them.

Part 3 – an industry of human trafficking and torture

In the absence of any other alternative, people in need of protection who are seeking asylum in Europe are forced to rely on criminal networks to organise their passage. Sold and resold from one intermediary to another, they are particularly at risk of violence and trafficking throughout their journey, especially in Libya.

After the death of family members, Fatma left her home in Eritrea at a very young age with her mother and two sisters to settle in Khartoum, Sudan. But her mother died in Sudan shortly afterwards, and Fatma found herself forcibly married at the age of 14. Years later, she decided to go to Libya to try to join Europe in order to study and live in peace.

Once in Libya, each leg of the journey to the coast costs migrants and refugees. Some believe they have paid for a trip from Agadez to Tripoli, but find themselves taken to cities like Sheba, Shweyrif or Bani Walid.

They are held captive there until they can pay an additional sum of money to be released or brought to the coast to attempt the Mediterranean Sea crossing. It’s such a lucrative business that convoys of migrants are even attacked by rival gangs, with their passengers captured for ransom.

While it is a widespread practice, some nationalities, like Eritrean, seem more systematically targeted by criminal networks extorting ransoms from them and their relatives through a system of money transfers spanning across several countries. They are perceived as being able to mobilise significant financial resources through diasporas in Europe and North America.

The conditions in the warehouses and other buildings where traffickers hold migrants and refugees are appalling. In some, hundreds of people are held in darkness, unable to move or eat properly for several months and subjected to the worst abuses to extort more money from them.

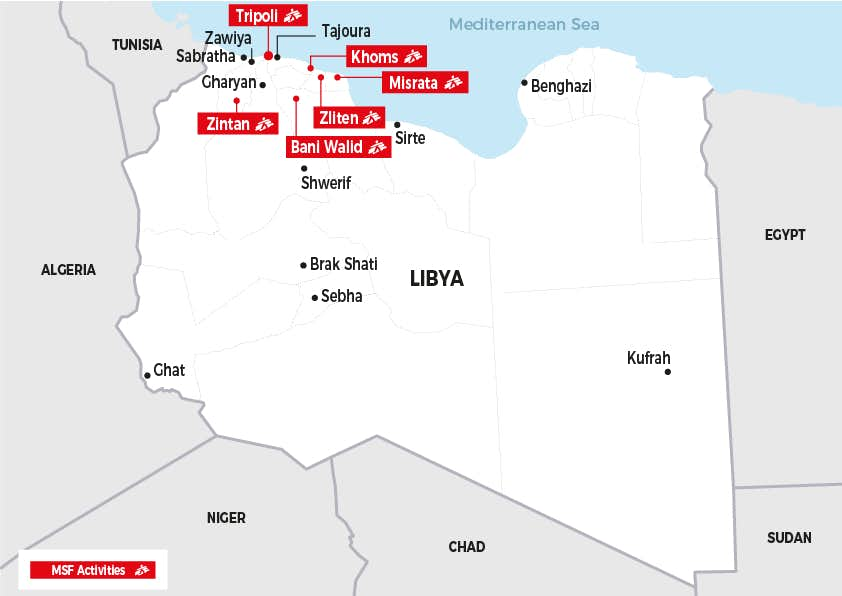

MSF does not have access to these prisons, but we treat some of those who managed to get out after paying their ransom, escaping or being released by jailers who no longer expect to get anything more from them. In Bani Walid, we are able to care for the survivors of the clandestine prisons still active in the area.

We have seen the scarred and broken bodies and heard stories of burning plastic poured on skin, daily beatings, and torture inflicted during a phone call to the victims’ relatives to convince them to pay. This continued to happen on a large scale in 2019 in Libya.

Their medical conditions tell of the ordeals they have endured. Shocked, anaemic, traumatised, these victims of torture and extreme violence will need many months to recover. In 2019, more than 20 people in critical condition were cared for by MSF in Bani Walid and transferred to hospitals in Misrata and Tripoli. A total of 750 consultations were carried out on site.

It is impossible to estimate how many people do not survive and die there in the desert from gunshots, beatings, injuries or tuberculosis and other diseases that kill them in such conditions.

Part 4 – Stuck between waiting, shipwrecks and detention

Libyan law criminalizes illegally entering, staying and exiting from its territory with a prison sentence and deportation, regardless of the individual’s potential protection needs. Today, Libyan authorities rarely carry out deportations from detention centres, but this has been reported several times in the east of the country.

In practice, refugees and migrants are detained without trial for an indefinite period. Their hopes of getting out are: returning to their countries of origin with the IOM, being evacuated to a third country by UNHCR, escaping, paying corrupt guards for their exit or, for some nationalities, finding a Libyan sponsor who can help release them.

Between a rock and a hard place

Once on the Libyan coast, those trying to reach Europe find themselves trapped in a cycle of waiting, followed by increasingly dangerous attempts to cross the Mediterranean, and periods of detention. With no official records, it is difficult to establish the number of migrants and refugees detained in the centres under the authority of the Ministry of the Interior. Their numbers generally range from 3,000 to 6,000, with the exception of the last months of 2017 when 20,000 people were crowded into unimaginable conditions after the transfer of thousands of people from Sabratha’s trafficking warehouses to Tripoli’s detention centres.

Conditions vary between detention centres. Some have seen improved access to water and proper sanitation, and overcrowding no longer reaches the record levels of 2017. But conditions remain inhumane and our teams continue to witness frequent abuses and acts of violence.

In the Dahr-el-Jebel detention centre, between the towns of Zintan and Yefren, nearly 500 people, most from Eritrea and Somalia, remain locked up. The majority is stranded in this mountainous region, south of Tripoli, after being transferred there in September 2018 during armed clashes in the capital. Away from the immediate danger of the fighting, they were forgotten by almost everyone.

When we began working there in May 2019, we were horrified to discover that at least 22 migrants and refugees had died of diseases, mainly tuberculosis. IOM and UNHCR were supposed to provide assistance, including medical care and protection services. Today the medical situation remains worrying.

Our teams working in this detention centre may not see widespread abuses committed by the guards that are common in other centres, but the protracted detention and the uncertainty are becoming every day more unbearable for our patients. More than a hundred of those held in the Dhar-el-Jebel detention centre are unaccompanied children.

An MSF doctor gives a detainee in the Dahr-el-Jebel detention centre a medical checkup. The centre holds nearly 500 people, most from Eritrea and Somalia. Libya, October 2019.

AURELIE BAUMEL/MSF

The Souq Al-Khamis detention centre, located by the sea in the city of Khoms, illustrates the violence and blurred lines between official authorities, militias and criminal networks that pollutes some detention centres.

Our teams have been working there since 2017. In 2019, Khoms became the main landing point for people intercepted at sea and brought back by the Libyan coastguard. It is also the starting point for many crossing attempts, including the one on 25 July 2019 which tragically ended with the deaths of at least 110 people.

Our team assisted 135 survivors brought back to Khoms. They were in a state of shock after spending several hours in the water and seeing so many people, including family members, drown before their eyes.

At first, it seems as though refugees and migrants detained in Souq Al Khamis have better conditions and more access with the outside world than in other detention centres. Here, some go to work outside, they can buy food in the city, speak to family on the phone, and, following recent IOM renovation work, hygiene conditions are no longer as dire as before. There are showers and access to safe drinking water. However, below the surface, lie stories of violence, sexual assault and human trafficking.

DANIEL, ERITREAN REFUGEE TRAPPED IN SOUK AL-KHANIS

“This is not a detention centre, this is a store for smugglers. Those who launch us onto the sea have their contacts here. They can come and talk to us, threaten us. Every night there are people who come with their guns.”

“Libya right now is about money, more than human lives. We know that smugglers are getting very rich. But we want to leave this country. That is what we are asking for. If it’s too much to ask, we’re sorry – but what else can we do?

I risked my life at sea to cross over, but they won’t let us pass. Europe refuses. I know that in 2011, when Muammar Gaddafi was overthrown by Libyan militias, the United Nations evacuated thousands of migrants from Libya to Tunisia. It is possible for them. There are not that many of us, it’s a matter of will. UNHCR listens to us, but it doesn’t help us with both hands, it just uses its fingers. I ask them to help us with their full hands and with all their hearts. We are not criminals, or people who want to cause problems for other countries.

I can be useful. I could have been useful to my country, but my government is only offering me the opportunity to be its soldier or slave. I need to be safe. Not for me, but for my wife. My wife is pregnant and I want to open a future for this child. I want him to be free as a bird. I want him to be able to make his own choices. This is not possible in my country. I never wanted to stay in Libya, I don’t want to cause any problems for the Libyans, I just want to leave.

UNHCR tells me to wait, to wait. How long will it last? I have been waiting in this detention centre for a year and a half already. I saw dead people, criminal activities, dead bodies on the beach. The world remains silent.

Today I am no longer afraid of anything. My wife was raped before my eyes when we were in Brak Shati in southern Libya. They broke her, but she’s still alive. She lives for me and I for her. Since I arrived in Libya, everything here is a matter of luck. We’re lucky we stayed alive.

I am talking to you in this detention centre and tonight they will certainly cause me problems because of that. They can kill me, beat me, separate me from my wife, as they have already tried to do. They’ve already done everything to me. But it doesn’t scare me. What more can happen to me? Nothing. I know it’s just a matter of telling my story, but it’s like a chain – if I don’t say anything, how will you know? I want to give my own words, I don’t want to be silenced. If I don’t talk, if no one talks, maybe the world won’t understand.”

Part 5 – Left to survive in town

Lucie’s experience gives a terrible insight into what can happen outside detention centres for a migrant woman brought back to Libya by the Libyan coastguard. In September 2019, she attempted for the second time to cross the Mediterranean.

After several hours, a plane flew over their boat, then a helicopter swung over their heads. Shortly after that, a Libyan coastguard boat approached them. All those on the boat were brought back to Khoms, where Marie met the MSF teams providing first aid and medical care.

After calling their smuggler, Lucie and two other people negotiated with the local security forces to be “put aside”. For 2,700 dinars (€1,730), they escape the transfer to a detention centre. They were held in a nearby house for a week, until the money was paid, and then transported to Tajoura, in the eastern suburbs of Tripoli.

In December 2018, after months of negotiations, Filippo Grandi, head of UNHCR, announced the opening of a transit centre in Tripoli, called the Gathering and Departure Facility (GDF):

““The GDF is the first centre of its kind in Libya and is intended to bring vulnerable refugees to a safe environment while solutions including refugee resettlement, family reunification, evacuation to emergency facilities in other countries, return to a country of previous asylum, and voluntary repatriation are sought for them.

(…) It offers immediate protection and safety for vulnerable refugees in need of urgent evacuation, and is an alternative to detention for hundreds of refugees currently trapped in Libya.

One year later, the hope for a place that would provide immediate protection and security for refugees, while a solution outside Libya was sought, has been definitively dashed.

Between July and November 2019, migrants and refugees released from Tripoli’s detention centres joined the few refugees for whom UNHCR has been able to secure a resettlement slot in a host country and who were awaiting their evacuation in the GDF.

In December, UNHCR announced that it was reassessing its role in an overcrowded GDF and acknowledged that it had little control over a facility primarily run by Libyan authorities, without unhindered access to international agencies nor freedom of movement for those held there.

UNHCR will have halted most of its support for the GDF by the end of 2020, and has recommended that people staying there should leave.

There are no other places that can provide a minimum level of safety for migrants and refugees in desperate need of protection from further immediate harm until a more durable solution is found, whether that is resettlement in a third country, voluntary return to their country of origin or another option.

Proposals to set up shelters, which are supervised by international organisations and where people are free to move as they wish, have so far been rejected by the various Libyan actors in charge.

The assistance offered by UNHCR and its partners in Tripoli to refugees leaving the GDF or released from detention centres is inadequate. It covers some cash assistance, some basic necessities and a follow-up of their request and medical situation.

There are no shelter or accommodation services; refugees must pay for accommodation on their own. They are once again at the mercy of kidnapping for ransom, forced labour, sexual violence and exploitation, and worse.

This is what happened to Samuel. He was released from the Gharyan detention centre in July 2019, after a journey that took him from his native Eritrea, where he was imprisoned for his political activities, to Libya, where he spent months in the hands of traffickers and then in the Dhar-el Jebel and Gharyan detention centres in Tripoli, where he was diagnosed with tuberculosis.

When he was released from the Gharyan detention centre and boarded a bus to Tripoli with staff from UNHCR’s NGO partners, Samuel thought he would be taken to the GDF. However, he was instead offered support through UNHCR’s urban assistance programme at its community day centre in Gurji, Tripoli.

Sick, weakened by two years of abuse and detention, and with 450 Libyan dinars (about €290) in his pocket, Samuel had to find a place to sleep and live. He was terrified of having to survive in Tripoli and came to believe that the Gharyan detention centre was a more enviable situation.

Since the end of 2015, the EU has mobilised €408 million for projects in Libya related to migration issues through the EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa. Almost half of the funds go to the protection and assistance of migrants and refugees in the country, mainly through UNHCR and IOM.

The EU has also earmarked €98 million for Libya from 2014 to 2020 to support various programmes, including migration control and the creation of an asylum system. On top of the €506 million from European taxpayers, several states channel funds to Libya as part of their bilateral cooperation.

The main objective for European states remains the containment of migrants and refugees in Libya, at any cost. The assistance and protection programmes they finance in Libya are in service to this and act to some extent as an instrument of this brutal policy.

Despite being properly funded, political constraints, security challenges, and a lack of transparency on the ground mean these programmes fail to meet even the minimum that could be expected from a humanitarian intervention. For humanitarian organisations working in Libya, the space for negotiation with the authorities is very limited.

When it comes to negotiating with the Libyan government and various local actors, UNHCR does not seem to receive any political support from the same states who give it significant financial resources.

Like other UN agencies, their operational deployment face severe constraints – with very few international employees throughout the country, mainly concentrated in Tripoli. Although the GNA derives part of its legitimacy from the recognition it receives from the UN, it does not recognise the UNHCR, one of the main UN agencies.

Libya has no asylum system and has not ratified the 1951 Geneva Convention relating to the status of refugees. Until October 2019, UNHCR was only allowed to register asylum seekers and refugees from a limited number of countries. There is political and financial leverage, but it is not used to ensure real improvements in the treatment of refugees and migrants in Libya.

Notions as simple and fundamental as the protection of asylum seekers or assisting people in the name of shared humanity and a centuries-old tradition enshrined in the 1951 Geneva Convention, have completely disappeared from the discourse of states and intergovernmental agencies on Libya.

They have been replaced by migration control. The hypocritical, cynical European states’ migration management policy and its dramatic consequences in Libya have long been exposed – and nothing has significantly changed, not even after the public outrage in 2017.

- There is an urgent need for humanitarian aid to be deployed more widely and transparently to migrants and refugees in Libya.

- The arbitrary detention of migrants and refugees must stop immediately. Shelters where they can be assured of security and assistance must be set up as a matter of urgency, while their evacuation can be organised.

- This can only work if Europe stops sending back those who escape by sea and if safe countries provide more places to welcome survivors.

*Names have been changed to protect identity

-

Related:

- Libya

- Refugees

- refugees and migrants