The latest Ebola epidemic in Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is the country’s tenth outbreak of the deadly virus in 40 years, and the worst ever documented here. This is the second-largest Ebola outbreak recorded anywhere.

DRC’s Ministry of Health officially declared a new outbreak of Ebola virus disease in North Kivu on August 1, after a case was reported in Mangina. The outbreak likely began months earlier, in May.

|

Ebola situation report as of January 28, 2019 Total cases: 736 Total deaths: 459 *Data published by DRC Ministry of Health. “Probable” deaths refer to deaths that were linked to confirmed Ebola cases but not tested before burial. |

MSF’s role

At the request of the Ministry of Health (MoH), Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) is part of the national task force coordinating the intervention on several pillars of the Ebola response:

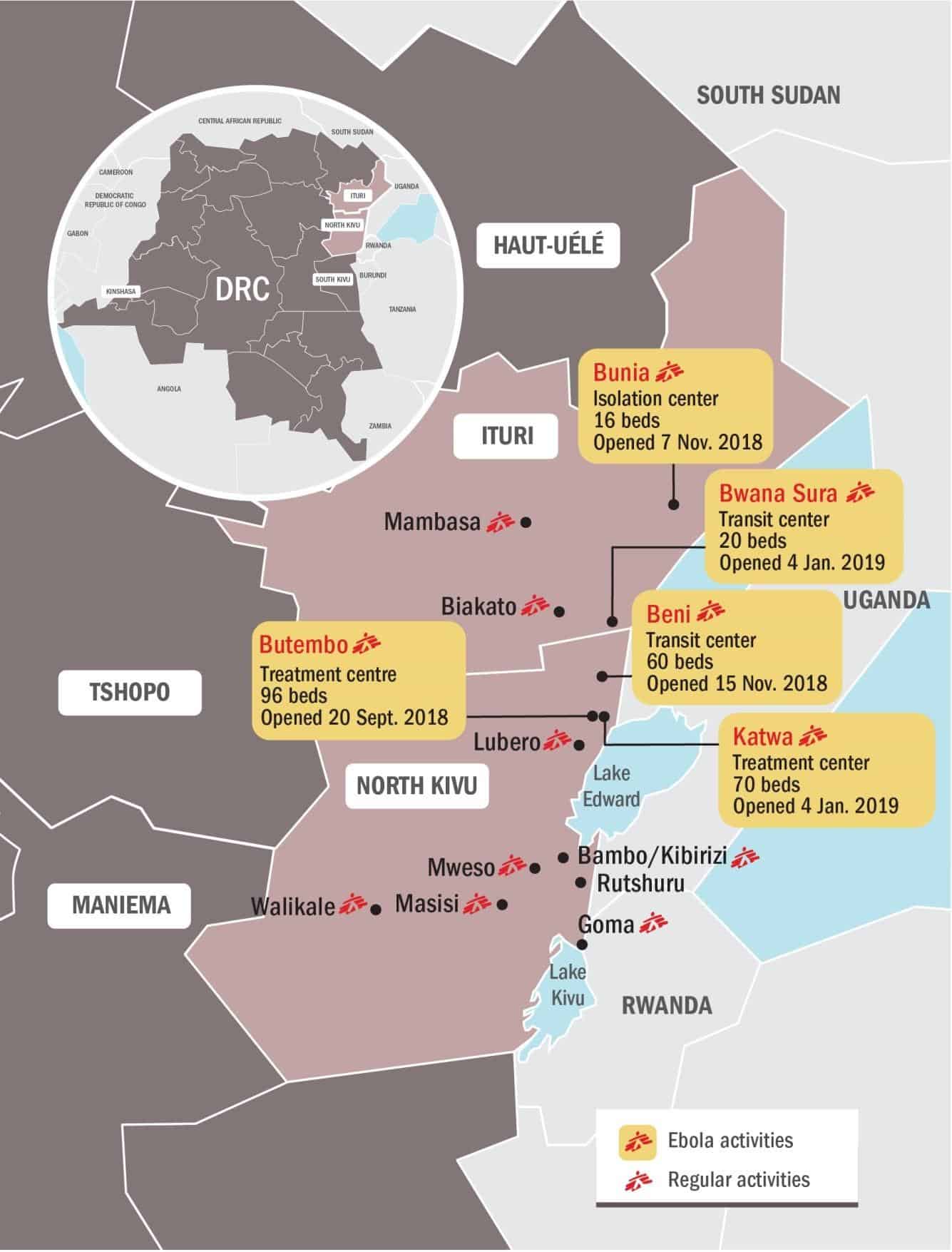

- Caring for patients affected by the virus (in Ebola treatment centres in Butembo and Katwa) and treating and screening suspected cases (in transit centres in Beni, Bunia, Bwana Sura, and Kayna);

- Communication & Health Promotion with the communities;

- Vaccination of frontline health workers in Ituri, Katwa/Butembo, Beni, Lubero;

- Infection Prevention & Control: protecting local health structures and health workers by helping with screening patients, hand and foot disinfection, capacity for short-term isolation of patients with suspected Ebola, and decontamination of the facilities where confirmed Ebola patients have transited;

- Training of staff;

- Supporting surveillance activities.

In total, more than 200 MSF staff members are currently working in Ebola projects in North Kivu and Ituri. (This total does not include MoH personnel working in MSF structures.)

As of January 27, 2019, MSF has received 3,292 people at its Ebola treatment centres and transit centres in the affected region. We have treated a total of 321 patients confirmed with Ebola.

MSF has so far vaccinated over 4,800 frontline health workers, particularly in the areas along the North Kivu-Ituri border and in Butembo.

Local context

The epicentre of the outbreak is in North Kivu province, a densely populated area in the country’s northeast with approximately seven million inhabitants. Despite the challenges of rough terrain and bad roads, the population is highly mobile. North Kivu shares a border with Uganda to the east and sees a lot of trade, as well as human trafficking and “irregular” crossings. Some communities live on both sides of the border and cross back and forth frequently to visit relatives or trade goods.

North Kivu has been an area of conflict for over 25 years, with more than 100 armed groups estimated to be active. Criminal activity, such as kidnappings, are relatively common, and skirmishes between armed groups occur regularly. Widespread violence has uprooted people and made some areas in the region quite difficult to access. While most of the urban areas are relatively less exposed to the conflict, attacks and explosions have taken place in Beni, a regional administrative centre, sometimes limiting MSF’s ability to run operations.

The current epidemic was first declared in the small town of Mangina, and the outbreak’s epicentre has appeared to move toward the south, first to the city of Beni, and later to the larger city of Butembo, a trading hub. Nearby Katwa became a new hotspot near the end of 2018, and recently cases have been found further south, in the Kanya area. Meanwhile, sporadic cases have also appeared in neighbouring Ituri province to the north, most recently in Komanda health zone.

Overall, the geographic spread of the epidemic appears to be unpredictable, with diffused small clusters potentially occurring anywhere in the region. This pattern makes ending the outbreak even more challenging. Given the appearance of new confirmed cases further to the south, the risk of the epidemic reaching Goma, the capital of the province, is another reason for concern.

The fact that some of the new cases are not linked to any previously known chains of transmissions is also worrisome, as it makes it more difficult to trace contacts and control the evolution of the outbreak.

Katwa is currently the main hotspot of the outbreak. Sixty-five per cent of new Ebola cases (68 out of 104 cases) recorded during the last three weeks come from Katwa.

A decision to postpone presidential elections originally scheduled for December 22 sparked tensions throughout the country, especially in pro-opposition strongholds such as Beni and Butembo. On December 26, the national electoral commission (CENI) announced that elections would be further postponed in three areas, including Beni and Butembo, because of the ongoing Ebola outbreak and the risk of attacks. This announcement resulted in violent protests, especially in Beni.

Amid the unrest in Beni, an MSF transit centre for treatment and screening of people with suspected Ebola was vandalized on December 27. The incident led to the temporary evacuation of the team. Of the 28 patients that were in the transit centre at the time of the demonstrations, nine people spontaneously left the centre, 18 were referred to a CTE run by Alima, and one was discharged. With no patients left, activities at the Beni transit centre were temporarily on standby; the centre opened again on January 1 and is now fully operational.

Several health centres in and around Beni were damaged during the December protests. Some of the health centres targeted had received support from our Infection Prevention and Control (IPC) teams to be able to properly screen and refer patients showing symptoms indicating Ebola. These attacks have both reduced the community’s access to general health care and reduced the number of facilities equipped to screen and refer suspected Ebola cases.

During the peak of insecurity, MSF also had to temporarily limit all activities outside the transit centre in Beni and the treatment centres in Butembo and Katwa. This resulted in the additional challenge of an accumulated delay in screening and treating potential confirmed cases, as well as identifying their contacts. Moreover, while IPC support was suspended, patients might have been contaminated inside health structures, accelerating the spread of the disease. Sick people have been known to visit more than one health centre before being identified as suspected cases and referred to an Ebola Treatment Center. This work is also made more difficult by the relative inaccessibility of parts of the region due to insecurity.

Since the beginning of this Ebola outbreak, almost 6,000 contacts have been identified, and more than 5,100 followed up by the Congolese Ministry of Health (MoH). Nearly 17,850 contacts have been vaccinated. The contact tracing and follow-up is done by the MoH with a team of epidemiologists.

Isolation, transit, and treatment centres

Beni: An isolation centre was built in early August 2018 by MSF in Beni. This was handed over to the MoH, which assigned it to another non-governmental organisation, Alima, and turned into a treatment centre. On November 14, in Beni, MSF opened a transit centre for suspected Ebola cases, most of them referred by the surveillance team (around 30 per day). The facility is located approximately 200 meters from the existing Alima Ebola treatment center (ETC), and confirmed cases are transferred by ambulance from the transit center to the ETC; those patients who turn out to be negative for Ebola are referred to other health structures in the area for care. The MSF transit center in Beni is currently operational with 60 beds.

Butembo and Katwa: An ETC built and run by MSF is operational in Butembo, a town estimated to be home to 800,000 people that became a hotspot for the outbreak in November, including seeing imported cases from Beni and other surrounding areas. Another ETC was opened in the eastern part of Butembo city, falling under the administration of the Katwa health zone. The Katwa ETC was inaugurated on January 3, and the first patients were admitted the following day. The total capacity will be up to 80 beds by the end of the month. The MSF ETCs in Butembo and Katwa are currently operational with, respectively, 96 and 52 beds.

Bunia: During the first week of November, MSF opened an isolation center on the premises of the General Hospital in Bunia, Ituri, with a hospitalization capacity of eight beds, a screening point at the entrance (with more than 2,000 people screened each day), and a small isolation unit for patients with suspected Ebola. The center is currently still active and run by MSF.

Bwana-Sura (Komanda): A 20-bed transit center was opened in Bwana-Sura, Ituri province, on January 4 following alerts reporting new confirmed cases in the area. This center is currently still active and run by MSF.

Kayna: On January 22, MSF opened an isolation center of 10 beds which will be soon be replaced by an ETC.

Other sites: An ETC was opened on October 12 following the appearance of confirmed cases in Tchomia, Ituri province, on Lake Albert (on the Ugandan border). This treatment center was handed over to the MoH on November 5, following an extended period with no new cases being reported. MSF supported the MoH personnel working in the center with training, logistic support, and technical expertise. MSF also operated a seven-bed transit center in Makeke for a few weeks (on the North Kivu-Ituri border), where patients with suspected Ebola could be isolated and tested for the virus and transferred to ETCs in Mangina or Beni. The center has now been closed because the MoH and IMC (International Medical Corps) opened an ETC in Makeke. MSF is no longer working in Tchomia and Makeke. In Mangina, MSF first helped to improve an isolation unit for suspected and confirmed cases that local staff had quickly set up in the Mangina health center, the first epicenter of the outbreak. Patients were cared for in the isolation unit while a new treatment center was being built. The treatment center opened on August 14. The ETC initially had a capacity of 68 beds; it has since been reduced to 24 beds and was handed over to IMC on December 7, as the volume of activity in Mangina dwindled and the focus of the outbreak shifted to other areas. There is no MSF activity in Mangina at present.

Developmental drugs

In these ETCs, MSF teams have been progressively increasing the level of supportive care (oral and intravenous hydration, treatment for malaria and other coinfections, as well as treatment of the symptoms of Ebola) and have also been able to offer new potential therapeutic treatments to patients with confirmed Ebola infection under the MEURI protocol. A team of clinicians makes the choice on an ad hoc basis between five potential drugs (Remdesivir (GS5734), REGN3470-3471-3479, ZMapp, mAb114, and Favipiravir). The treatments are given only with the informed consent of the patient (or a family member if the patient is too young or too sick to consent), and are provided in addition to supportive care.

These five drugs have not passed all steps of clinical testing yet and we are unable to measure their efficacy. The utilization of these developmental drugs has been approved by the ethical committees of the MOH and MSF, because it is believed they may improve a patient’s chances of survival. While caution must be exercised, these treatments are an added resource to the response. Because these drugs remain untested, their utilization is subject to a strict protocol which places particular emphasis on the informed consent of the patient.

On November 21, the MoH announced the official start of the randomized clinical trial (RCT) of ZMapp, Mab114, and Remdesivir. Without a general agreement amongst partners, the previous protocol needed some important improvements. Some of the main issues to fix, for instance, were the inclusion of REGN-EB3 in the trial and an adaptation of the analysis model, as the current one is considered not likely enough to yield useful results. The protocol was amended to reflect these concerns and the new version has been approved as of December 24. MSF will implement it in the Butembo and Katwa ETCs. So far, the randomized clinical trial is being conducted only in the ETC run by Alima in Beni.

MSF teams are training staff to be able to run the trial in our ETCs. We expect to start the trial on January 30 in Butembo and in early February in Katwa.

Infection prevention and control

In addition to patient care in ETCs, MSF is active in several pillars of the Ebola intervention. One priority is to ensure that the health system remains functional for non-Ebola patients, and that patients do not get infected with the virus while seeking care in health facilities. Health centers that have seen Ebola-positive cases are visited by MSF teams and decontaminated. We support some of these structures to implement infection prevention and control measures, such as training staff on the proper triage of Ebola suspects, setting up isolation areas in case of need, and providing material for all these activities. This activity has been deployed by MSF in the Beni, Butembo, Katwa, Komanda, and Bunia health zones at different times, depending on when and where positive cases are identified. For example, in Beni we currently support 20 health centers of various sizes—most of which were damaged during the December protests.

Rapid response team

One of the most critical components of the Ebola response is the ability to react quickly to new alerts, investigate, and decide on whether to set up new structures for the intervention. MSF has set up a Rapid Response Team (RRT) composed of experienced Ebola staff from other MSF projects : a medical doctor, a nurse, a water and sanitation expert, and a community engagement specialist. Last fall, this RTT investigated alerts in Luotu, a village outside of Lubero, in response to alerts of a positive case. The team was involved in case investigation and also in building a small isolation unit for patients with suspected Ebola. As no confirmed cases were found, MSF withdrew its staff on September 27 from this center, leaving the structure to the MoH. The same team was deployed to Tchomia when the first confirmed case appeared there in October 2018.

In December a second specific team composed of a team leader, a specialist in community engagement, an anthropologist, an epidemiologist, and a water and sanitation expert started operating in remote rural areas with activities such as pre-triage, decontamination, IPC, and community awareness-raising. This was part of an effort to refer as many Ebola cases as possible to the treatment centers and limit disease transmission. The team was put on standby following the increased tensions in late December.

The RRT has recently been dispatched to the Kayna health zone, further south, an area located one day away from Goma by car. The team is generally based in Katwa, close to the area of intervention, and visits health zones surrounding Butembo city with active Ebola transmission.

Vaccination

MSF has mostly been involved in vaccination of frontline health workers, those most exposed to the virus. In total, MSF has vaccinated more than 4,800 frontline health workers, particularly in the areas along the Ituri-North Kivu border and in Butembo. Vaccination will be starting soon in Bunia.

Surveillance

The surveillance strategy is led by the MoH/WHO. MSF epidemiologists in Beni, Butembo, Katwa, and Komanda support surveillance activities.

Health promotion

MSF health promotion teams in Beni, Butembo, and Katwa work in support of the IPC teams and vaccination teams, as these activities require intensive communication with the community. The health promotion teams are also in contact with local leaders of several health zones to exchange information about Ebola and about the community. MSF also runs health promotion activities in Bunia (Ituri) and in support of the MoH-led vaccination campaigns.

Emergency preparedness

MSF’s regular projects in North Kivu and Ituri provinces have been supplied with equipment including personal protective equipment (PPE) and have installed proper hygiene and infection control protocols to safeguard staff and patients from the risk of contamination should the epidemic reach these locations.

MSF remains ready to support local authorities—as well as neighboring countries—in the implementation of their response to the Ebola outbreak in DRC.