India has the highest burden of both tuberculosis (TB) and multi-drug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) based on estimates in the WHO Global TB Report 2022. The country accounts for 28 percent of the global TB burden.

In its clinic in Mumbai, MSF provides free, comprehensive diagnostics and treatment services to people with severe forms of drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB). DR-TB is a form of antimicrobial resistance that is difficult and costly to treat. It is caused by TB bacteria that are resistant to at least one of the first-line existing TB medications, resulting in fewer treatment options and increased mortality rates. MDR-TB is caused by what are defined as TB bacteria that are resistant to two of the most important TB drugs, isoniazid and rifampicin.

MSF also supports TB diagnostics and treatment at a public DR-TB treatment centre in M-East Ward (MEW), Govandi, Mumbai, in collaboration with the National Tuberculosis Elimination Programme (NTEP).

Bedaquiline (the use of which was first approved in December 2012 by the U.S. FDA) was one of the first new TB drugs to become available in half a century and offers hope for people with MDR-TB. Delamanid is another newer drug that has been available in India since 2019. Without these newer drugs, treatment success rates for MDR-TB are below 50% and in extensive resistance cases the treatment success rate drops to just one in four.

Duration of treatment with bedaquiline is six months, with extension for patients meeting certain criteria. In recent years, the MSF Mumbai clinic has been receiving increasing numbers of patients whose bedaquiline-based regimens have failed and have very few treatment options. Patients have failed treatment due to the rest of the regimen not being effective, including a lack of delamanid where necessary, or treatment not being extended for more than six months when required.

“When I recover, I want to play cricket”

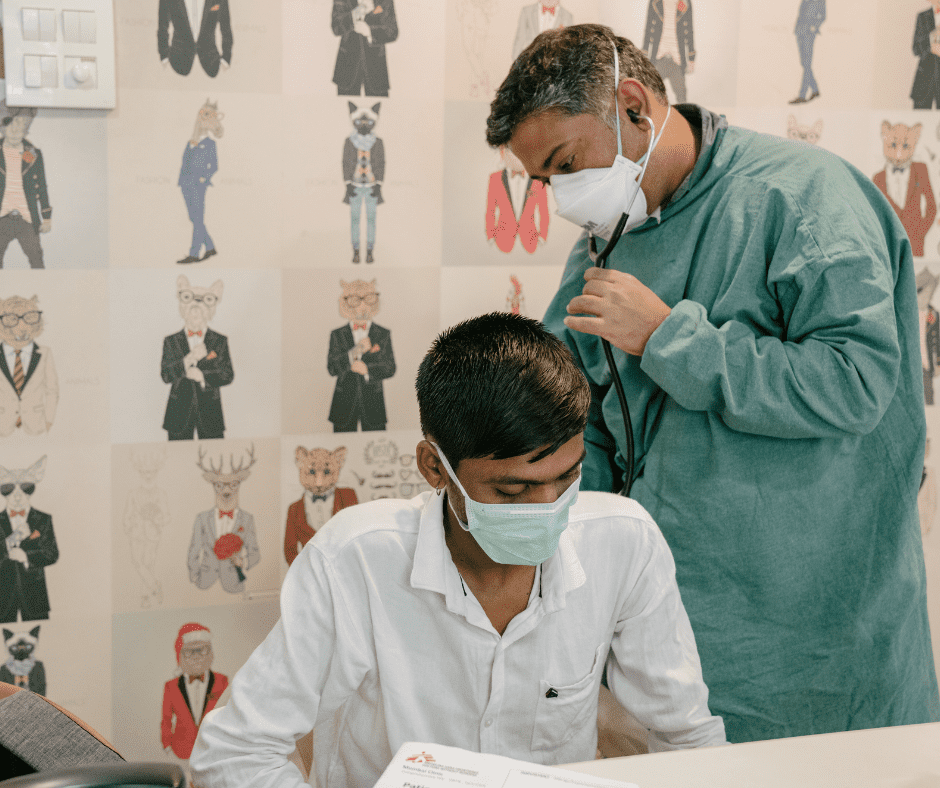

23-year-old Deepak Shegar is so much more than his condition. He aspires to have a career in the garment industry, loves cricket, and wants to get his hands on a brand-new bike. But it took him years to get to this point where he can work towards his goals and fulfill his dreams.

Deepak was diagnosed with DR-TB in 2018, just after he had started working. Under immense financial pressure already, his future looked bleak. But since he started a successful treatment, things have turned around.

Deepak lives in east Mumbai’s Vikhroli along with his family. A year after his diagnosis, Deepak’s mother, Gunabai, was diagnosed and treated for drug-susceptible TB, which means that all of the first line TB drugs will be effective as long as they are taken properly. Treatment is a combination of for drugs taken together. Gunabai, who is now healthy, had raised Deepak and his younger brother Rohit all alone by working tirelessly at a construction site. Their father, Subhash Shegar, a rickshaw puller, had succumbed to TB in 2009 when Deepak was just 10 years old. At 14, Deepak had to leave school to earn money for his family.

In 2018, Deepak was suffering from fever, cough, and had been vomiting for several days and had lost a lot of weight. Because of his family history, he feared what the symptoms meant and decided to get tested for TB. When Deepak was first diagnosed, he was scared for himself and his family because there was stigma against this illness. He felt that his life, dreams and ambitions would fall apart. Before he fell sick, he could support his mother with a monthly salary of Rs 6,000, but the disease meant he could not work for at least three and a half years. The family ran from pillar to post to help Deepak recover. There were times when they could not afford three square meals a day as they pooled all their resources for treatment related expenses.

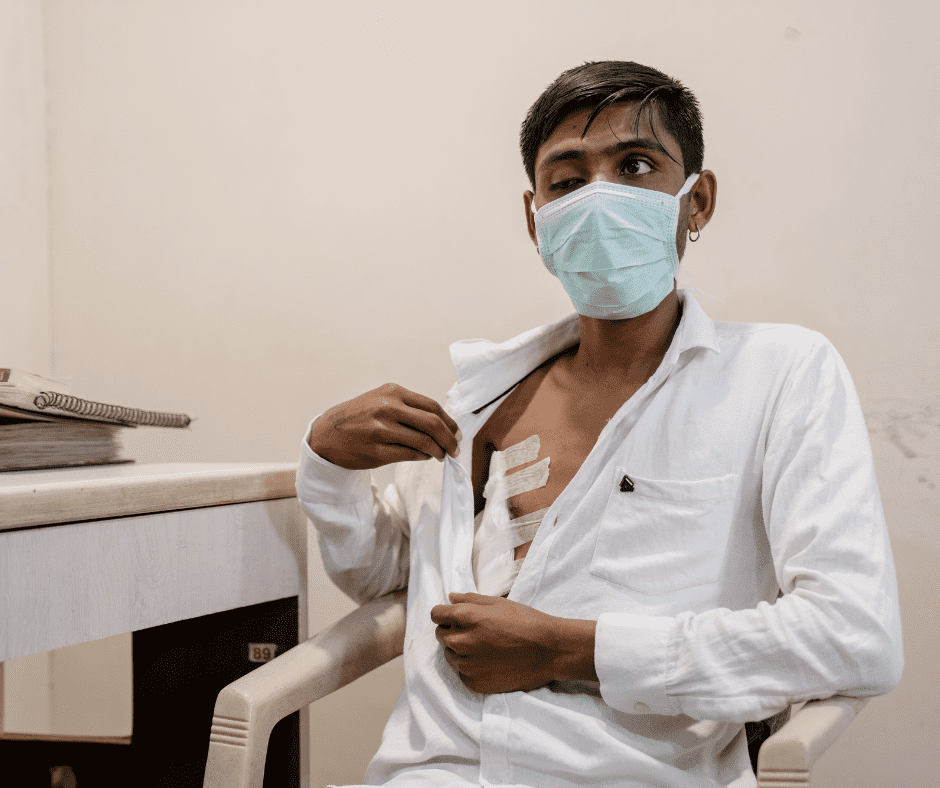

Initially, Deepak was admitted to the Powai Government Hospital in central Mumbai, where he was given an injectable drug called Kanamycin every evening for six months. The side-effects were so strong that they disrupted his daily life. He suffered mild hearing loss and could not walk properly because of the pain of the daily injection. Due to the disease, he suffered from breathlessness, extreme fatigue and a cough. He had stomachache due to the different medications, and that caused him difficulty in eating. Deepak also faced the issue of fluid retention in his lungs and to treat it, a tube was inserted into his lungs to help extract the fluid. Although the tube remained for a year, the method proved futile. He was then referred to MSF clinic by the Sewri TB Hospital.

Once he was at the MSF clinic, based on the clinical assessment he was considered eligible for lung surgery and was the first person to be referred to the National Institute of Tuberculosis and Respiratory Diseases (NITRD) in Delhi for this. He underwent the operation at NITRD and his tube was finally removed. Later, he was put on a regimen of the DR-TB drugs bedaquiline and delamanid as well as intravenous treatment with the injection imipenem. After almost two years, his treatment was completed in November 2022. He has now fully recovered and will finally resume his work in the garment business.

Deepak’s journey during his treatment has not been easy. Apart from the financial and physical exhaustion, living with DR-TB also subjected Deepak to emotional and mental agony. When his friends found out about his condition, they stopped talking to him. Ostracised by friends and community, Deepak locked himself in a room, fearing judgement and the condescending gaze of society. He also at times considered taking his own life. He says, “On those difficult days it was my family that kept me going. They were my rock even during the most turbulent times. I would not have come this far if they had abandoned me. I also received counselling at the MSF clinic and that was a huge help.”

It was his willpower, ambition and courage that helped him in overcoming the challenges. “I enjoy designing clothes and once I recover fully, I am going to completely immerse myself in this craft. Currently, I work for only 15-20 days a month and that is why I do not have a stable income. But I am hopeful that in the future I will be able to earn Rs 18,000 every month,” he says,

Deepak is focused on getting better each day, now more than ever. Consuming a nutrient-rich diet, comprising of fish, chicken and meat, he keeps track of his ‘thrice a week’ protein regimen religiously. His younger brother Rohit, has been a pillar of emotional support throughout Deepak’s treatment. Rohit was a ray of hope to the despondent family, says Deepak.

While Deepak has been advised to avoid physical exertion for now due to his condition, he says, “When I recover, I want to play cricket to my heart’s content.”

Conversations with her ‘window friend’

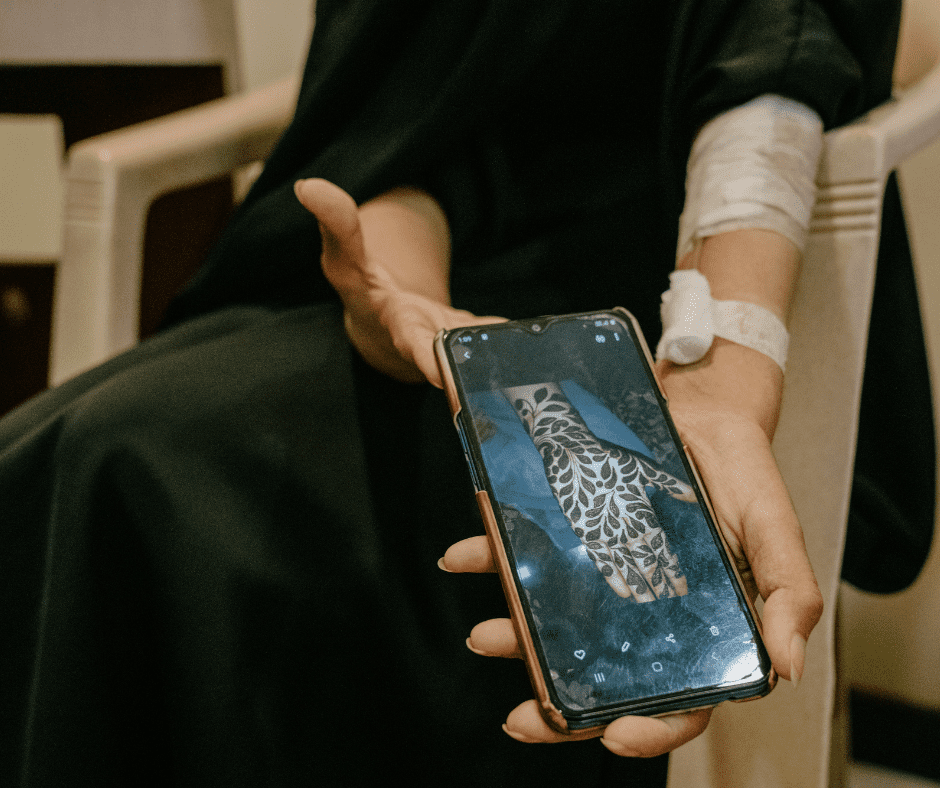

Anam (name changed on request), a bright 17-year-old, excels not only at English and Science in school but is an equally good Mehndi/henna artist. She tells us happily that she has completed a professional Mehndi course and learnt needlework. She aspires to become a fashion designer.

She scrolls through her phone gallery, bringing up photos of the bridal henna designs that she has created. As her hand moves over the screen, there is a contrast between those delicate designs and the pattern on her own hand from the PICC Line (Peripherally Inserted Central Catheter).

Anam was first diagnosed with pulmonary TB at the age of nine. Before her diagnosis, she frequently had a cough and a fever. When her mother initially took her to a doctor, she was suspected of having double typhoid.

Being diagnosed with TB at such a young age came as a blow to Anam’s family, who had no history of the disease. Her mother later got to know that Anam studied with around eight to ten TB positive patients in school. The stigma around the disease is so strong that other children or their families never informed the school authorities. The parents feared that their children would be expelled, bullied, harassed or discriminated against. Anam’s mother decided that it was important to break this lethal chain. She informed the Principal and did not send Anam to school for the next five months.

For 14 months, Anam received treatment at a private hospital with support from her immediate family and friends. However, the treatment did not work and her symptoms such as weight loss and vomiting worsened. The treatment at the private hospital cost her family around Rs 5,500 monthly (Rs 2,500 for medicines and Rs 3,000 for tests). In February 2021 she was finally diagnosed with drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) at a government DR-TB centre. She was put on a DR-TB regimen, however subsequent investigations revealed additional resistance to other drugs as well. She suffered from cough, fever and weight loss. Since her condition was not improving with the treatment received so far, she ultimately came to MSF.

At the MSF Clinic, Anam was put on a regimen of the oral drugs bedaquiline, delamanid, linezolid and amoxicillin, and an intravenous treatment with the injection imipenem. This regimen was built for her based on her resistance to certain drugs and she has been taking it for the last one and a half years.

Anam’s mother says, “We have been through a very rough patch, but we found help every step of the way. The psychosocial support in terms of counselling, and the medical support that we received at the MSF clinic reduced our financial and medical treatment worries.”

Despite constant encouragement and support, every day Anam is also witness to another TB story unfolding outside her bedroom window. The impact of stigma and lack of awareness about TB is having serious consequences for a girl not much older than Anam in the neighbouring house. Anam recalls distraught conversations with her ‘window friend’: how she has been locked inside her room because of the disease; how her parents have abandoned her; and the irregularity of her meals. Anam’s mother says that their neighbours don’t allow other community members to help them. Bereft of medical and psychosocial support, her ‘window friend’ developed suicidal tendencies that resulted in one failed attempt to jump off the roof.

Anam realises that her friend’s parents may have prevented the suicide attempt, yet they contributed nothing to alleviating the everyday suffering. No proper treatment is sought, she says. Anam’s mother tried to counsel the girl’s parents but they are reluctant to listen to anyone.

The story of Anam and her ‘window friend’ highlights the importance of medical treatment and psychosocial support in TB treatment, and the importance of raising awareness around the disease and fighting stigma. And for Anam, even a small dream like hanging out with friends on a vacation post-recovery, keeps her going.