Rebutting pharma’s rejection of a global COVID-19 IP waiver

By Felipe Carvalho, Yuanqiong Hu, Leena Menghaney

In response to the COVID-19 “TRIPS waiver” proposal submitted by South Africa and India for a temporary waiver from certain pharmaceutical intellectual property (IP) obligations at the World Trade Organization (WTO), Thomas Cueni, the director-general of the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers and Associations (IFPMA) recently published an opinion piece in The New York Times that spoke up against the waiver and in support of keeping the current industry-led IP monopolies in place during the pandemic. Here the authors vigorously rebut Cueni’s position and examine how and why his arguments are flawed.

Many of the points made by Cueni in his opinion article are very familiar to those of us in the access-to-medicines movement and have been debunked in a myth-busting briefing document published by the Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) Access Campaign. However, given the crucial importance and timing of current discussions at the World Trade Organization (WTO) that he is seeking to influence, and the platform he has been given, we believe it is important for us to respond to certain comments in his article. This attention also presents an opportunity for us now to examine in the harsh light of the COVID-19 pandemic how the premises held by Cueni and IFPMA’s allies are without foundation.

On the “threat” of the waiver to medical innovation

While Cueni acknowledges the “legitimate concern” on access to COVID-19 patents, he nevertheless claims that “the [waiver] effort would jeopardize future medical innovation, making us more vulnerable to other diseases,” despite evidence to the contrary.

Contrary to IFPMA’s fearmongering about the future of biomedical innovation, this pandemic has already demonstrated that it is completely possible to accelerate research and development (R&D) primarily driven by public health needs and public funding. This reality reflects what has long been shown in the many analyses and studies that have challenged the pharmaceutical industry’s demands for ever more and longer IP protections in the name of innovation.

Again the evidence of the last few months contradicts Cueni’s claim that IP has played an indispensable role in generating COVID-19 R&D outputs or securing R&D investment, and that the current patent system is robust and necessary for pharmaceutical innovation. On the contrary, there have been highly visible examples during this pandemic in which pharmaceutical companies’ “business-as-usual” exercise of IP rights have impeded timely availability and accessibility of needed medical tools. And our own experience as a medical humanitarian organisation has shown how the present IP system fails to deliver innovation to the people who need it most.

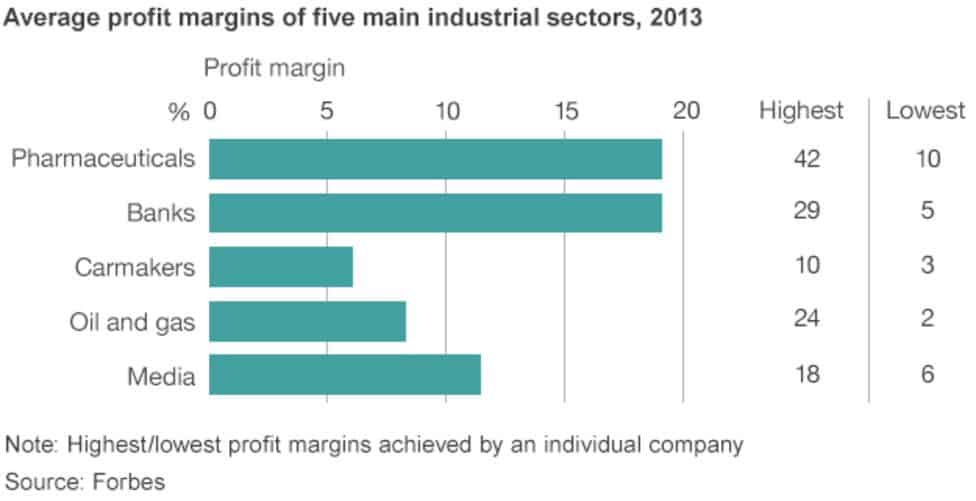

The pharmaceutical industry enjoys some of the largest profit margins on earth, even surpassing the oil and gas industries. Yet, contrary to the claim that the profits gained through IP-backed monopolies are necessary to recoup the cost of R&D and to invest in future research, studies have demonstrated that pharmaceutical companies spend more of their profits on marketing, repurchasing shares, handing out dividends, and heaping lavish pay packages on company executives.

The industry abuses the patent system to make higher profits

To maximise profits, large pharmaceutical corporations have long pushed for looser IP standards to acquire and prolong market monopolies. Many big pharmaceutical companies are living off profits garnered from evergreening patents on decades-old drugs. At the same time, they have pushed for stronger enforcement of the monopolies thus acquired, so that they can exploit and secure more private rights at the cost of the benefits to society — in the case of medicines, this cost is counted in people’s lives.

By enabling companies to generate profits through monopolies and consequent high prices, the current patent system caters to the treatment needs of the few who have the means to pay, whilst ignoring the millions of people across the world who either go into debt to raise money for patented treatments or are told to wait until the patents on the drugs expire.

The industry upsets the balance between rewarding innovation and benefiting society

The pharmaceutical industry’s modus operandi has upset the balance of the patent system, which was conceived to reward innovation on the one hand, and secure the benefits of that innovation for society on the other. Big Pharma has only one interest in the patent system and that is to use it as a business strategy to block competition and keep prices high. This has led to dramatic increases in healthcare costs around the world. This systemic flaw has been clearly documented by the United Nations among others, though it continues to be denied by large pharmaceutical corporations. If IFPMA wants to talk about the “eroding” of the patent system, then this is the place to start the investigation.

On the role of the public sector in medical innovation

Cueni acknowledges the reality of governmental support for research but claims that “governments have neither the money nor the risk tolerance to take over the role of business” and that “directing government labs to manufacture medicines…would politicize drug development.” Yet ironically, in this pandemic, it is indeed governments that the pharmaceutical industry has pushed to shoulder the risk and liabilities of developing and providing the COVID-19 medical products. This protection from liability is of course in addition to the pharma industry receiving massive public funding and regulatory support to accelerate the development process. More generally, while public investment has always played an important role in funding new medical tools and technologies at the early stage of the research, what the pandemic demonstrates is that governments are playing a highly significant and enabling role also in other stages of the development, production and delivery of medical tools and technologies.

On the same topic, Cueni seems to overlook the fact that many countries, including high-income ones such as Australia and Canada, are now mobilising government laboratories to produce and provide vaccines and medicines as needed. Contrary to IFPMA’s claim, in fact, it’s only recently in the last two or three decades that some countries have stopped producing essential medical products in publicly funded facilities. In many middle-income countries, including Thailand and Brazil, public-sector manufacturers have played a crucial role in providing domestic access to medicines to address the country’s treatment needs, including in the HIV epidemic. Public production of medicines is a totally reasonable strategy to lower health inequalities.

On fair distribution of new COVID-19 products

We can all agree with Cueni that there needs to be fair distribution of COVID-19 vaccines and medicines. But for Cueni to single out the vaccine nationalism of rich countries as the sole cause of unfair access is simply hypocritical and incorrect.

If Big Pharma genuinely embraced the principle of ensuring equitable and timely access for all, they should have never entered into any of the bilateral advanced purchase agreements for COVID-19 vaccines and medicines with wealthier countries to begin with. They should have published their licensing agreements to establish transparency and accountability and taken concrete actions to share openly all technologies and IP to facilitate maximum diversity of production and supply globally. None of this has happened. Instead the corporations have rushed to clinch deals with rich countries and can’t even deliver for all of the demands. The result is that millions of people are now left at the back of the queue for COVID-19 vaccines and medicines.

On the “misjudgements” of the past

So much for the present. Cueni also makes a clumsy pass for the forgiveness of the industry, with an admission of what he calls “a terrible misjudgement” in the past. He is referring to the legal case, 22 years ago, when 39 pharmaceutical corporations sued the South African government over its legal reform to procure affordable generic HIV medicines at the height of the AIDS epidemic. This was indeed a seminal moment that rallied millions of people around the world to prioritise lives over profits. Cueni says things have changed since then. We only wish this were the case.

In reality, for more than two decades after that momentous case, the industry has continued to hold countries hostage for safeguarding public health in their IP laws and practices. The list is long. To name just a few examples:

- In 2007, Abbott retaliated against the Thai government’s issuance of a compulsory license on Abbott’s two patented HIV medicines and one antihypertension medicine, by refusing to market its new medicines treating other diseases in the country.

- In 2006–2013, the Swiss corporation Novartis put India’s patent law on trial for seven long years to weaken the country’s legal norms against patent evergreening, a lucrative game for the pharmaceutical business to prevent generic competition.

- In 2013, Eli Lilly sued the Canadian government because the company could not fulfil Canadian law’s requirements in its patent applications on two antipsychotic medicines.

- In 2017, after Gilead failed to fulfil legal requirements for exclusive protection on the hepatitis C medicine sofosbuvir, the company threatened to sue the Ukrainian government for future profits.

- In 2019, Malaysia faced pressure from the pharma industry on the issuance of a compulsory license on prohibitively expensive sofosbuvir.

In all of these cases, patients suffered as a result of the industry’s actions.

Why the global IP waiver matters and what it can do

If IFPMA and its allies would like to sincerely make amends and correct the “misjudgement” of the past, we need more than words about supporting equitable access. Unfortunately, IFPMA does not seem to want to take any action in this direction.

IFPMA rejected an initiative encouraging voluntary sharing of IP and technologies, and now raises objections to the TRIPS waiver proposal, despite the fact that both proposals are clearly designed to address global access concerns.

In essence, the struggle lies between corporate power and public health, and only a political solution will resolve this contest. The TRIPS waiver proposal for COVID-19 provides exactly such an opportunity for a legal and political resolution.

Like any other policy or legal intervention, in isolation the TRIPS waiver will not solve all of the challenges of access. With its specifically defined scope and timeframe, the waiver is targeted at resolving some of the challenges associated with IP on key medical products and technologies for COVID-19.

It addresses the very real concern that corporations are quietly amassing patents and IP that they could enforce once public attention wanes on COVID-19, as well as patents already impacting supply, such as Gilead’s monopoly on the drug remdesivir. The waiver would ease the bureaucratic burden of health ministries to identify IP on pipeline treatments. It mitigates the limitations of the existing legal options under international law that offer piecemeal solutions only for individual countries and for individual products. The waiver also provides clear and consistent direction to patent offices and courts on how to view the granting and enforcement of IP in the midst of a public health emergency and prevents the possibility of disputes that could delay local manufacturing and supply.

As cases of COVID-19 continue to rise in many countries around the world, neither governments nor the public should be fooled by this unconvincing display of half-hearted humanity by the pharmaceutical industry as set out by Cueni. This is simply a new chapter of the same access crisis, caused by the same structural factors that we have been seeing over and over again.

However, the waiver proposal at WTO is an opportunity for concrete action to help prevent yet another tragic repetition of the past when it comes to access to lifesaving treatment. At the same time, the current debate provides a timely opportunity to look beyond the business-as-usual paradigm of biomedical innovation, and instead work towards building a more just, equitable, transparent and accountable medical-innovation system that truly serves public health needs.

-

Related:

- Access to Medicines

- COVID vaccine

- COVID-19

- Patents