More than 10,000 nurses are providing healthcare in Médecins Sans Frontières’ humanitarian programmes worldwide—the largest single professional representation in MSF.

To mark International Nurses’ Day on May 12 and celebrate our diverse nursing staff, MSF highlights the sometimes underestimated contribution of nurses in our intensive care units (ICUs), treating severely sick patients who may otherwise have no access to lifesaving critical care.

‘Nurses work hard so loved ones can go home safely’

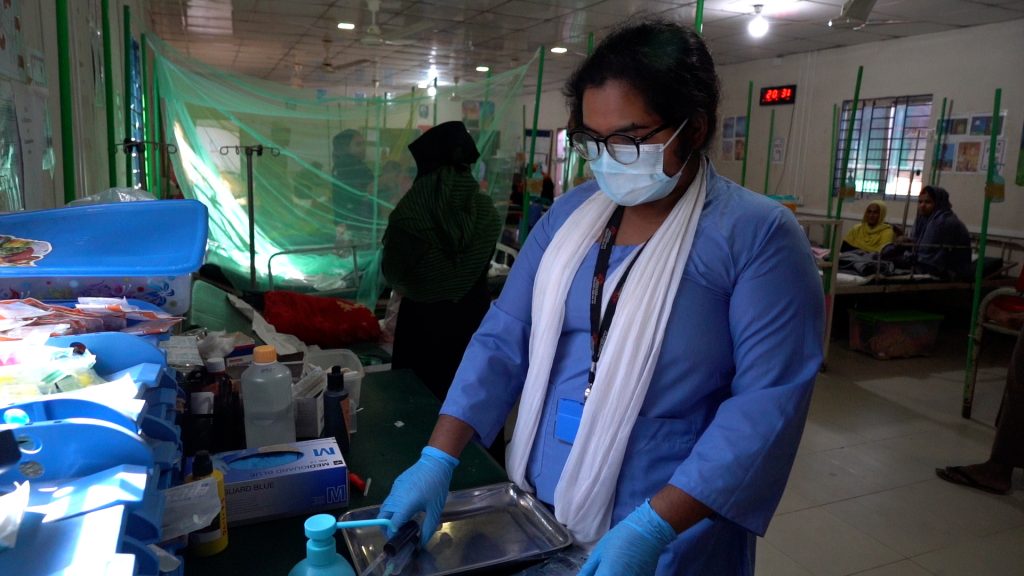

As an intensive care nurse in Goyalmara Mother and Child Hospital in Cox’s Bazar, Noami Biswas is committed to providing patient-centred care for severely sick children and their families.

In the MSF hospital paediatric intensive care unit (ICU), Noami and the multi-disciplinary team treat young children with life-threatening conditions such as severe pneumonia, meningitis, septic and hypovolemic shock, while also involving their families in their child’s care.

“The best thing about being a nurse is connecting with patients, with their family and helping them in their bad times when they need us the most,” says Noami.

“We involve them in everything from the beginning. With patient feeding, we involve the mother all the time because they need to know how to feed the baby. We explain to the patient, mother and family – fathers also.

“Last year there was a patient with meningitis. She was admitted into our hospital and she was dying. And we were [initially] going to give her palliative discharge. But we tried [to treat her]. Her father was there. We involved him in our treatment. He was constantly sitting with us, helping with the baby’s positioning and everything.

“And after 23 days, she healed and she went home. It’s a very successful story for me.”

When parents and patients might be struggling psychologically, Noami draws on the support of the mental health team, who can help them manage their tension, worry or grief.

Everyone in the ICU can be deeply affected.

Skilling up to provide critical care

“In ICU there are so many critical patients. We have ten beds and two isolation beds, and we are almost full every time. We are giving cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), Ambu ventilation [manual ventilation using a bag-valve-mask]. So this is different to the normal ward.”

With only basic nursing training behind them, Noami and her colleagues have welcomed training in paediatric emergency care and in the use of CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure), which is especially useful to treat respiratory distress.

“Before [having the] CPAP machine it was really difficult to continue with treatment,” explains Noami. “But after CPAP, patients are now getting better in two or three days.”

A new era of nursing

Noami’s nursing aspirations began in childhood. “There was a time when my mom was in the hospital, I saw some nurses there and they were really helpful. They were so caring. They inspired me. I thought, ‘I can [be] like them.’”

When Noami started working with MSF in 2021, at the height of the COVID-19 crisis, nurses seemed to inspire people worldwide. According to Noami, the pandemic changed how people perceive nursing in Bangladesh too.

“There was a time in Bangladesh that nursing was not a preferable profession. But nursing in Bangladesh is developing now. After COVID we were highlighted, and now people like us.”

To the younger nurses: I say, come

The global shortage of healthcare workers is all the more urgent in nursing. The pandemic has also revealed the need for substantial investment in nurses’ education, support and wellbeing. But Noami hopes others will be inspired just as she was.

‘Nursing is my calling’

Gessica Fleurmond’s family knew from early on that she was destined for nursing. Now, Gessica is a highly experienced intensive care nurse, and she and her colleagues help hundreds of trauma patients each year in MSF’s Tabarre hospital in Port-au-Prince, Haiti.

In Haiti, surging gang-related violence and crime alongside road traffic accidents contribute to the consistently high demand for trauma healthcare.

“In the intensive care unit (ICU), we receive patients with head trauma, closed or open abdominal trauma, and also vascular wounds in the upper or lower limbs. They need intensive care because they’re in a life-threatening condition, they need to be closely monitored, they need to be cared for,” says Gessica.

As an intensive care nurse, Gessica must be prepared to deal with anything and everything. But, she says, seeing someone in very bad shape is always tough. “For instance, when we know a patient won’t make it… You do the work, you provide the care, you give the medication, but you already know that this person won’t make it. It’s quite difficult and painful, especially when the parents visit.

“If the team sees that the patient is not going to make it, we talk to the psychologist, the psychologist meets with the family, and then with the doctor and the nurse, we see the family again, we explain what happened, what we think, what we are going to do. For the family, it’s very sad, sometimes they go crazy, they run, they collapse, crying, but it needs to be done.

Intensive challenges

A collaborative team is always important when delivering quality healthcare, but perhaps even more so in settings like Haiti, where resources aren’t optimal.

“There’s a lack of equipment in the hospitals, and there is a lot of frustration among the staff because we feel constrained and limited. The nurses are competent and qualified, they can work anywhere, sometimes in remote areas replacing a midwife or a doctor. But a lot of equipment is missing,” says Gessica.

Another challenge is a lack of specialist training. “I did not receive any specific training to become an ICU nurse. With flexibility, adaptability, you learn every day… to work and develop the right skills.

“At MSF, I received training on intubation, on resuscitation, patient positioning, all that.”

A calling

Despite the challenges, Gessica knew from early in her life that she had certain strengths that led to a career in nursing.

“My ability to become a nurse was discovered by my grandmother and my sister. They thought that I took good care of the ones I loved and that I made sure everything was done as well as possible. This is what led me to pursue this career. I thought that maybe it was my calling.

“What I enjoy most about my job is when we receive a patient in a very bad condition, and we help them get better until they make a full recovery.”

One particular patient had a profound impact on Gessica. “Two years ago, a child was admitted here. He was eight years old. He had been the victim of a road accident with very severe injuries to both his legs. When the patient came in, he was fully aware of what was happening, and he was able to express it normally. It made quite an impression on me because he was only eight years old.

“He explained the accident, what he was experiencing, what he felt. It was really tough, some of us even cried. And it was especially hard for the parents because they blamed themselves for sending their child run an errand, so they believed that if they hadn’t sent him out, this wouldn’t have happened.

“He was in severe pain, needing very high doses of morphine analgesics [pain relief medication]. After weeks of care, we were able to save one of his limbs. Now he has fully recovered, he can easily run and walk with a prosthetic leg. This made a strong impression on me because he was a child, it was a very serious accident, he could have died but he was strong, physically and morally, especially morally. He believed in the future and he didn’t give up. It really, really left a mark on me.”

Looking to the future

“What I wish for this generation of nurses in Haiti is that they be firm, but at the same time gentle, that they have a lot of empathy, love, great ethics, dedication, and also a lot of courage, because it does take courage. Yes, because the country is almost pushing us to give up but if you only look at the negative side, you’ll get discouraged before you even enter the hospital. We need to focus on the patients, because they need us.”

Gessica is a strong communicator with a passion for sharing a message. And as a qualified sign language interpreter, she’s able to speak with people who are hearing impaired or have a speech disability, another way she contributes to providing access to care. “I love this language,” she says.

Communication no doubt strengthens her ability to connect with patients.

Saving mothers from near death in Nigeria

In Jahun, northern Nigeria, women and girls are admitted daily to the Médecins Sans Frontières maternity department intensive care unit with life-threatening complications in pregnancy or childbirth. Registered critical care nurse, Theophilus Tyonongu, has followed in his parents’ footsteps to bring his skills and compassion to the unit’s lifesaving work.

Nigeria is estimated to account for more than 1 in 4 of all maternal deaths worldwide.1 Globally, the top five causes of maternal deaths are considered mostly preventable. These include preeclampsia and eclampsia, a form of high blood pressure in pregnancy; postpartum haemorrhage; and severe infection, all seen in MSF’s ICU in Jahun. Yet they are only preventable if they are detected early and people can access skilled care without delay.

For women seeking healthcare in Jahun there are multiple obstacles that affect individuals’ and families’ choices and cause risky delays, according to Theophilus. “People require admission into ICU because they usually come to the hospital late and when things have already gone very bad. For some the villages are very far, so they can’t really come to our centre any time.

“If somebody has been in labour since Monday [their family] might […] keep them till Friday, which is market day. They will put the patient into the vehicle that is going to the market, and [only] then be able to bring the patient to the hospital, in a very critical state.”

Thirteen per cent of women giving birth in the maternity department in 2022 were under 18 years of age. Although these teen mothers are often married, decision-making is a challenge for most married women in the culturally conservative communities of northern Nigeria, and especially so for young wives.

“The grandmothers or the mothers have to make decisions for them, or the husband”, say Theophilus. “But we do the best we can and recommend the best that is possible for them.”

Hearts that stop

Severe heart problems are not unusual among the women in intensive care.

“We manage a lot of pulmonary oedema [excess fluid in the lungs], which is mostly cardiogenic, so either from heart failure or from post-partum cardiomyopathy [difficulty pumping blood] and other heart-related issues,” says Theophilus.

“One of the patients we had, she came from a referral facility, which is also a general hospital. It was a transition [change of shift] period and I came earlier than I was supposed to, so I started taking over some basic things, and I took over from the person that brought her in. Unfortunately, she arrested just a moment after she was admitted into the ICU.

“We were able to resuscitate her, and then we managed her from that time until we actually discharged her. So it was a scene of joy, seeing how much it did to her, and the impact that was able to create for her.

“I’ve been with MSF for roughly two years, and I’ve been working in ICU for up to 11 months now,” says Theophilus. “Usually we have three nurses in ICU. Around Fridays and Saturdays and Sundays, we usually have a lot of very severe cases to manage.”

Being equipped to meet the high workload has sometimes been a frustration for Theophilus and his colleagues.

“The patients we have here sometimes are more critical than those that are being managed in our referral centres. We are operating a level two ICU [ed: in MSF ICUs go up to an MSF-designated level 3] and we do not have all the sophisticated equipment we need. But there has actually been a lot of improvement—then some trainings also. This really helps to strengthen the team, and you see a lot of changes in the team dynamics, in the approach, with the patient-centred approach, and the way we work together. Knowledge always brings a lot of changes.”

Improving nursing care, generation by generation

Theophilus grew up steeped in healthcare, with his two parents working in hospitals and forming close bonds with their patients. “I saw how they assisted people, how they helped people. Some of them even became family friends from there. So I saw the impact they made in people’s lives and I actually chose to follow this and be able to do more from where they stopped,” he says.

His background and training also make him a keen observer of the successes and challenges of nursing in Nigeria today.

“Nursing in Nigeria is actually developing very fast. There are a lot of improvements, there are a lot of innovations and creativity that is coming from the part of the Nursing and Midwifery Council of Nigeria.

“But I can see there’s a high rate of under-employment, though there’s still a shortage of nurses in the country. Some nurses’ own goals are not met as some may desire. So there’s a high rate of emigration, to [places] where they feel they might have a better experience and be able to meet their personal goals better.”

Theophilus’ ambitions burn strong nonetheless, invested in the next generation. “What I would like to see in my country is a generation of nurses that are more committed to their work: passionate, and more scientific. So I would love them to put more energy than this generation again. I [also want to see] more specialties in nursing, more nurse academics in the population, to be more outstanding. And bring us in Nigeria to a point where we can be at shoulders with every other country.”

Dedicated to care in a conflict zone

In the Médecins Sans Frontières Trauma Centre in Aden, Yemen, nurse Anis AbdRaboh Dayan has been witness to the brutal toll of gun violence and civil war on adults and children.

Anis has been working as an intensive care nurse in MSF’s trauma centre for almost its entire 11-year history. He has reflected deeply on the impact of war, and nursing.

A young boy’s legacy

Anis was inspired to become a nurse after his own medical emergency as a young boy. “I fell to the ground, developing a bleeding wound. I was in so much pain. That’s when a nurse at the emergency department received me. He treated me very nicely, eased my fear, bandaged me and gave me medication. I loved nursing from that day on.”

As an adult, it’s another young boy’s story that has left an indelible mark on Anis, and his colleagues.

“I will never forget, as long as I’m alive, a little boy about five years old. He came from a distant village with a gunshot wound to the abdomen. It took a lot of time until he arrived and he lost a lot of blood. The lack of blood led to a lack of oxygen in the brain, resulting in brain dysfunction.

“He couldn’t walk and couldn’t talk. As the nursing team in the intensive care department, we developed a treatment plan [for him]. Besides the medication, the therapeutic part, we thought about psychological support, and bought him games, in addition to allocating time to sit with him and sometimes with the family and the child, trying to draw him out.

“But the miracle happened. It was a beautiful feeling, and most of us cried. He got out of his bed… And he started walking in front of us. And he thanked us, with his eyes, lips and hands, pointing at us.”

Stepping up to intensive care

“I started in the inpatient department taking different training and exercises in dressing and giving injections and figuring out how to work in accordance with the protocols,” says Anis. “Then I moved to the intensive care department, which is a very sensitive department.”

Designated as level three, the Aden ICU provides the highest level of advanced critical care in MSF. The team sees trauma affecting people’s chest, abdomen, pelvic area, feet, hands and blood vessels. Many patients have experienced dangerous delays in reaching the hospital, which complicates their condition.

For Anis, it was an important and exciting step to move into the ICU—particularly as there aren’t many opportunities for nurses to advance their careers in Yemen.

“[MSF’s] theoretical and practical exercises and training were at the highest level,” he says. “I gained more experience in terms of mechanical ventilators for the patient, and how to deal with a patient who suffers from a vascular injury, or after large and complex operations such as laparotomies. I felt like I was experiencing a shift, a turn [in my life]. It was new! It forced me to have more skills.”

Greater recognition for nurses still to come

According to Anis, nurses are still underestimated and under-recognised, but it’s time for that to change.

MSF’s Goyalmara Mother and Child Hospital was established in 2017, with a focus on supporting Rohingya refugees and the local Bangladeshi community in Cox’s Bazar with maternity and paediatric care. In 2022, 1,975 children under five years of age were admitted for paediatric care including 1,398 who received intensive care in the paediatric ICU. The hospital also admitted 1,082 newborns for care, including into the newborn ICU.

MSF has worked in Haiti since 1991. The trauma hospital in Tabarre was established in 2019 and provides emergency, surgical, burns and psychological care and physiotherapy. The hospital has a 50-bed trauma ICU and an additional 20-bed ICU for severe burns. In 2022 the teams treated 316 people in intensive care.

MSF teams run the maternity and neonatal departments of Jahun general hospital, in Jigawa state, Nigeria, in collaboration with the Ministry of Health. They provide free and comprehensive obstetric and newborn care, and support basic obstetrics in four health centres to reduce complications during pregnancy. In 2022, we admitted 12,621 women to the maternity department, assisted 7,900 births, and treated 1,890 women for severe complications in intensive care.

The MSF Trauma Centre in the southern coastal city of Aden, Yemen, was opened in 2012 to manage patients suffering acute trauma due to active conflict. The hospital provides general and orthopaedic surgery (excluding neurosurgery, maxillofacial, ophthalmology) as well as mental healthcare, physiotherapy, and laboratory and microbiology services. In 2022, 392 patients received care in Aden ICU.