PORT-AU-PRINCE/NEW YORK/PARIS — As the world marks 10 years since a devastating earthquake struck Haiti, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) reflects on our response to the disaster a decade ago and highlights the current deterioration of medical care in the country in a new report.

“The catastrophic earthquake killed thousands of people, displaced millions, and destroyed 60 per cent of Haiti’s already dysfunctional health system,” said Hassan Issa, head of mission with MSF in Haiti. “Ten years later, most medical humanitarian organisations have left the country, and Haiti’s medical system is once again on the brink of collapse amid an escalating political and economic crisis.”

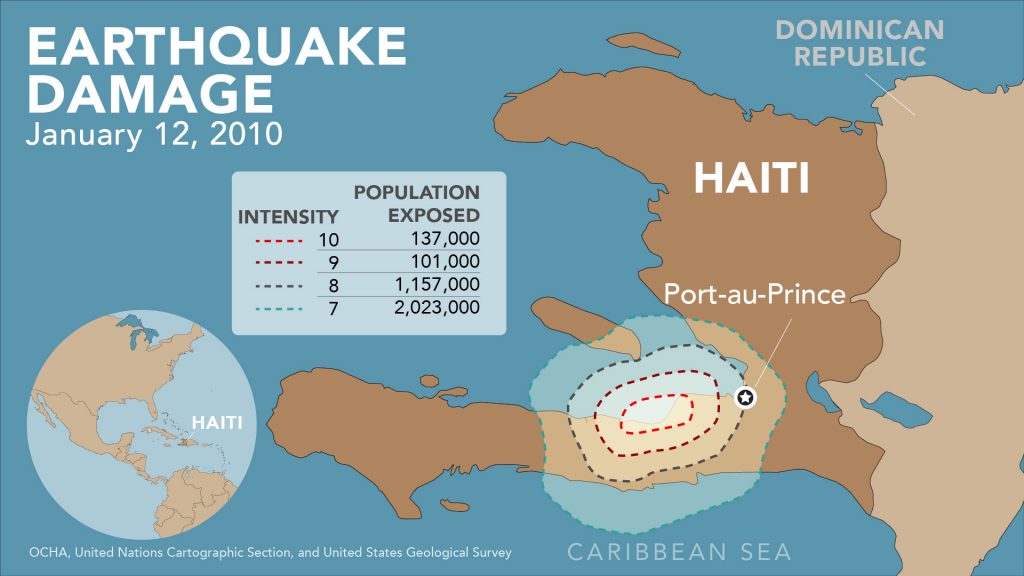

On 12 January 2010, the magnitude 7.0 earthquake devastated Haiti. MSF, which had been present in Haiti for 19 years prior to the earthquake, lost 12 employees that day, and two of the three MSF-supported medical facilities were seriously damaged.

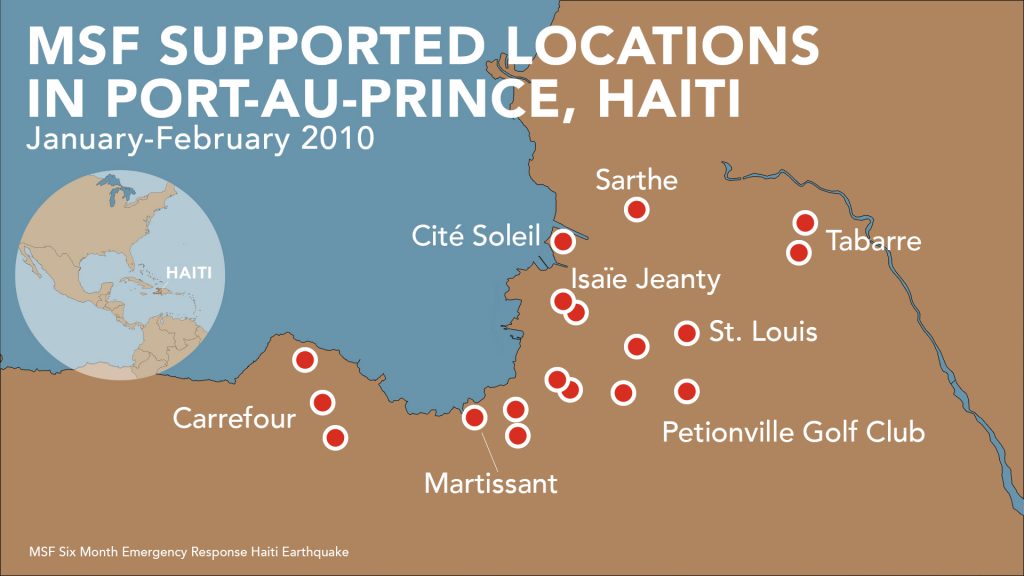

In response to the urgent and almost unlimited needs of people, we mounted one of our largest-ever emergency operations, treating more than 350,000 people affected by the earthquake in just 10 months.

Ten years later, as economic troubles and political tensions have intensified, medical facilities – including those run by MSF – are struggling to meet the needs of patients. A new report, Haiti: Ten Years On, highlights the challenges for medical facilities to function in the face of political and economic strife.

Since a hike in fuel prices in July 2018, which spurred the crisis, medical facilities have struggled to provide basic services due to shortages of drugs, oxygen, blood, fuel and staff.

“The international support that the country received or that was pledged in the wake of the earthquake is now mostly gone or never materialised,” said Sandra Lamarque, MSF head of mission. “Media attention has turned elsewhere as daily life for most Haitians becomes increasingly precarious due to raging inflation, lack of economic opportunities, and regular outbreaks of violence.”

In 2019, Haiti experienced multiple months-long countrywide shutdowns (known as peyi lok in Haitian Creole, or ‘locked country’). Streets were blocked by barricades made of burning tyres, cables, and even walls built overnight that hindered the movement of ambulances, healthcare workers, medical supplies, and patients.

In 2019, MSF’s emergency stabilisation centre in Martissant, Port-au-Prince, received:

In 2019, MSF’s emergency stabilisation centre in the Martissant area of the capital, Port-au-Prince, received an average of 2,450 patients per month, 10 per cent of whom had gunshot wounds, lacerations, or other injuries from violence.

Our burn treatment hospital in the Drouillard area of Port-au-Prince saw a peak in activity in September, when we admitted a total of 141 patients with severe burns, primarily caused by accidents.

In Delmas, where we run a sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) clinic, there was a drop in the number of patients during this period of heightened violence, simply because it was too hard for patients to reach the clinic.

In rural areas, such as Port-à-Piment in the South department, the effect of the crisis on the Haitian healthcare system is painfully visible. MSF has long supported emergency and maternal health services in the area. In severe cases, when hospitalisation is necessary, we now struggle to find an open facility where we can refer our patients.

The South department’s main hospital and blood bank both closed in October after being looted and are still not fully functional. We now regularly transport patients in critical condition up to five hours away to find a hospital that can accept such cases.

In the North department, where MSF was about to open two SGBV clinics, activities had to pause due to access issues and lack of fuel.

In response to the deepening economic and political crisis, we have launched new initiatives to care for patients when the Haitian medical system cannot cope. In November, MSF reopened a 50-bed trauma centre in the Tabarre neighborhood of Port-au-Prince.

In its first five weeks, the trauma centre received an overwhelming 574 patients. One-hundred fifty people suffering from life-threatening injuries were admitted, 57 per cent of whom had gunshot wounds.

We are also reinforcing our assistance to the Ministry of Public Health and Population by organising donations of medical equipment and material, rehabilitating facilities, and training staff at Port-au-Prince’s main public hospital. MSF is also supporting a hospital in Port Salut in the South department and 10 health centres throughout the country.

“We knew we were meeting a need here in terms of serious and urgent cases, but obviously the situation is even worse than we imagined,” Issa said. “We now need others to pay attention to the current medical needs in Haiti.”

-

Related:

- 2010 Haiti Earthquake

- earthquake

- Haiti

- MSF in Haiti