From its beginnings, humanitarian documentary photography has sought to inspire compassionate action. But too often, a lens of Western white privilege has repeated stereotypes of powerless victims that create distance from the viewer rather than solidarity.

Doctors Without Borders has not been immune to this pattern. We were founded by both doctors and journalists in 1971 with the dual mandate to provide medical care where needed most and to speak out about the realities we witness. Documentary photography has long been an essential tool to raise funds, raise awareness and recruit staff. We often presumed to be “voices for the voiceless”. But of course, everyone has a voice, including those who have been intentionally silenced or marginalized.

-

- A Venezuelan migrant lifts up his one-year-old daughter shortly before going to sleep on the sidewalk in the central square of Tumbes. Like other newly arrived Venezuelan migrants, they sleep outdoors because they do not have enough money to pay for lodging. ©MAX CABELLO ORCASITAS

-

- Zia-ur-Rehman, Head of Sanitation and Labour for MSF in Timergara, shovels the waste that was collected from various departments of the DHQ hospital in the incinerator on the 6th of December, 2020. ©Khaula Jamil

-

- Shahid Khan helps his son Abdul Rehman with his homework inside their home in Machar Colony. Shahid Khan has successfully completed his hepatitis C treatment, Karachi, Pakistan. ©Asim Hafeez

-

- My name is Bigirimana, I am 48 years old and the father of 10 children. I come from Kabati in the Masisi territory. I fled the war in Kabati to the Bulengo camp, where I stayed for two years. I fled because of the war, but I’m going back now because the situation has improved in Kabati. I’ve been back in Kabati for a week now. It’s quiet and I sleep very well. There are no problems. In the camps we didn’t receive any humanitarian aid, it was so hard, many of my relatives had been victims of bullet wounds and bombardments. Some had been killed by armed groups on the road and others had received stray bullets during the fighting. We need medicine. Most of us are ill, with diarrhea, especially the children. Hunger makes us suffer. I’m going to start cultivating the fields again. ©Daniel Buuma

Reality check

In 2020, more than one thousand current and former staff of Doctors Without Borders signed an open letter denouncing “racism and white supremacy that shape the culture and mindset that still defines our organization: the white European ‘expert’ and the ‘distant other in need’.”

Rooted in colonial history, such “white savior” stereotypes distort the current reality in Doctors Without Borders: Four out of five of our colleagues are hired locally in the countries where we work. Of those who leave their home countries to work internationally, two-thirds come from Africa, Asia and Latin America. Their perspectives, voices, and images — those closest to the places where we work — should be at the center of our story.

-

- Rihana, a 28-year-old patient participating in the endTB-Q clinical trial, sits for an audiometric examination in a soundproof booth to verify her hearing capacity during a routine consultation at the endTB clinic run by Interactive Research & Development (IRD) in Kotri, Pakistan. The trial aims to test a short treatment for a very hard-to-treat form of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis -an airborne infectious disease that has grown resistant to standard medications: pre-extensively drug-resistant TB (pre-XDR-TB). endTB is a 7-year partnership among Partners In Health (PIH), Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), Interactive Research & Development (IRD). ©Asim Hafeez

-

- A physiotherapist is manipulating the hand of a burn patient at MSF hospital in Tabarre. ©MSF/Marx Stanley Léveillé

-

- Due to the war that broke out in 2020 in Ethiopia’s Tigray region, more than 17,000 Ethiopian refugees have settled across the border with Sudan in Um Rakuba camp. Melu Bedliho, 32, was displaced to Um Rakuba camp in 2022. She is now living in the camp. She gave birth to her second child in the camp. ©Faiz Abubakr

-

- Amer, a 36-year-old Syrian refugee in Lebanon holds his empty hypertension medication. The country’s economic crisis, coupled with recent security measures, have made accessing medication a nightmarish struggle for many non-communicable-disease patients. ©Carmen Yahchouchi for MSF

-

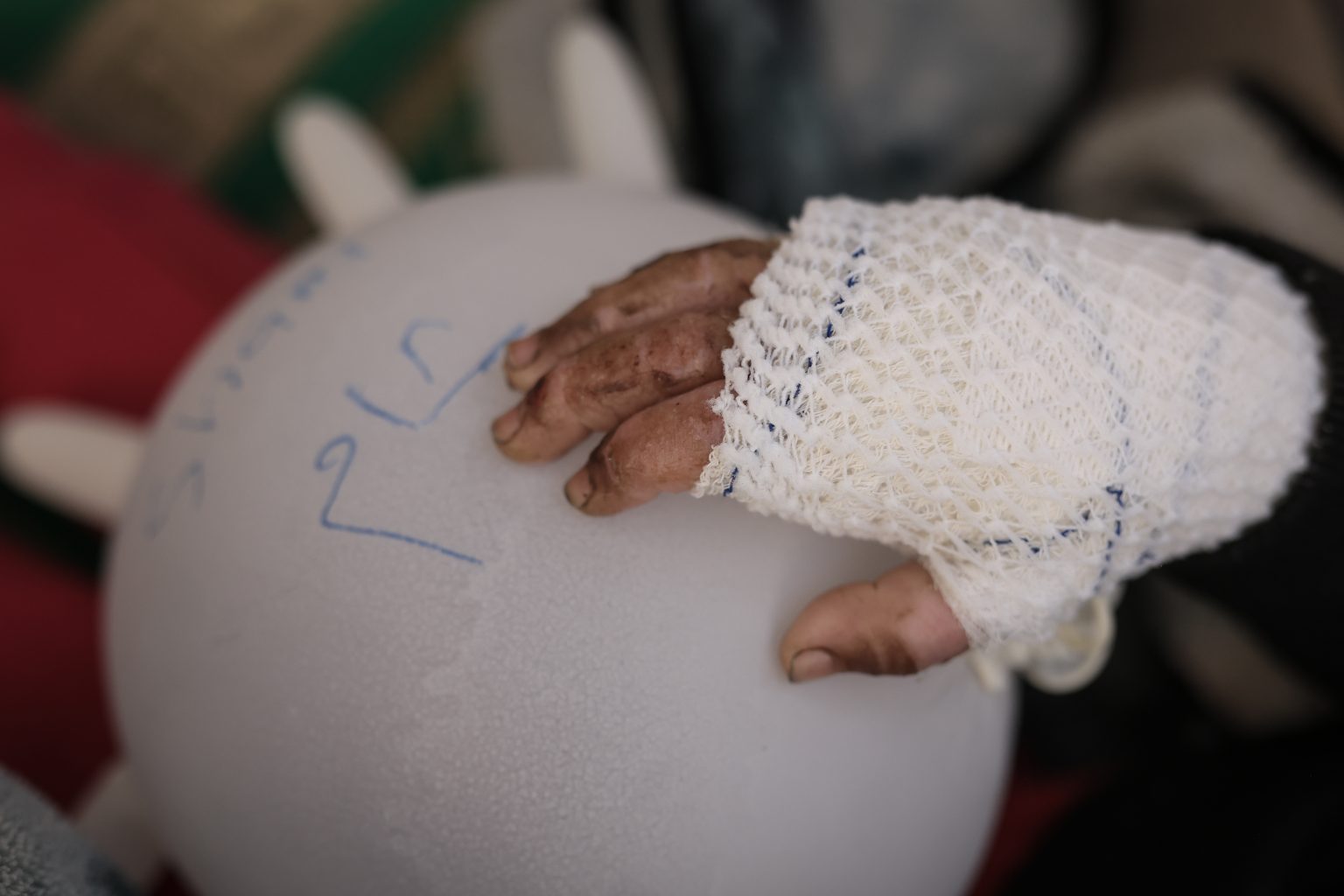

- Aisha (14), Yemen. Aisha was 6 months old when a candle fell onto the mattress where she was sleeping. Her family assumed she was dead until they heard her cries. Since 2015, over 13 power stations have been damaged across Yemen due to war, leading many families to depend on candlelight. Aisha received injuries to her head, face, and hands, which resulted in limb amputation and years-long treatment. She has been treated in several stages at the MSF hospital in Amman. Aisha is an artist: she draws, knits, and makes accessories. The first time I met Aisha, she was wearing a Yemeni dress splattered with paint. We were at the hospital’s art school with Mais, a mental health counsellor. MSF hospital, Amman, Jordan. May 2024. ©Rehab Eldalil/MSF

-

- Maya [name changed to preserve anonymity], a Syrian refugee in northeast Lebanon, releases a dove she tends to in her family’s tent in Arsal. A widow and a victim of child marriage, Maya has endured severe mental trauma, especially after the death of her daughters in a fire. Maya now looks for ways to heal herself and those around her through preaching communal care and mental health support. However, the recent anti-refugee sentiment in the region has made it difficult. ©Carmen Yahchouchi for MSF

-

- Veronika Nyabol Knom, 39 years old, fencing off her plot of land to prevent goats from eating the seeds she has just planted. Internally Displaced Camp population (IPD) camp, Bentiu, Unity State, Rubkona County, South Sudan. Isaac Buay/MSF

-

- In Al Shate’ Refugee Camp in Gaza City, a man is riding his bicycle through the midst of the destruction. ©MSF

From voices for the voiceless to nothing about us without us

Decolonizing our storytelling requires changes on both sides of the camera. Our new visual standards promote diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) and an anti-racist approach for both those producing our images and those represented in them:

- Prioritizing photographers from the regions portrayed whose portfolios demonstrate ethical storytelling

- Active collaboration and co-creation with patients and local staff

- Informed consent to ensure that people understand and affirm how their image will be used

-

- Melwa, 65, a Rohingya refugee, in MSF’s Kutupalong field hospital in Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh. She fled her home in Myanmar in 2017 and has been living in the camp ever since. She comes to the hospital to collect her medication. At 65, Melua found herself amidst upheaval. As tensions escalated, her family made the difficult decision to leave their home, eventually arriving at the camp on Eid Al Adha in 2017. Facing the pressing decision of what to carry with her, Melwa recalls, “In the urgency of it all, I grabbed a few essential documents and our family portraits: my daughter’s birth certificate and a family photo. I even left behind clothes that I had freshly washed.” Melua ‘s choice was rooted in pragmatism. The documents were not only emblematic of her family’s history but could also have potential utility in uncertain times ahead. This was a stark contrast to the relatively peaceful times they had experienced before the outbreak of violence around Eid Al Adha. She remembers her earlier life in Myanmar with unmistakable clarity: the pillars of her home, the fence, the stretch of land she owned, the chickens, and her favorite spot for meals. Any mention of her homeland brings forth an emotional response from her. “It’s hard to talk about it without shedding tears,” she admits. Yet, her thoughts on returning are contingent upon certain conditions being met. “For us to consider going back,” she explains, “there has to be an assurance of safety, non-discrimination, citizenship rights, and opportunities for the next generation—especially access to education.” In a place of displacement, it’s this hope for a brighter and educated future for her descendants that drives Melua’s spirit forward. ©Mohammad Hijazi/MSF

-

- Aisha (14), from Yemen working on a handcraft artwork in a workshop at the MSF hospital art school. During her latest treatment visit to the hospital, between April-May 2024, Aisha learnt how to make use of her prostethics to gain independence, through occupational therapy sessions. MSF hospital, Amman, Joran. April 2024. ©Rehab Eldalil/MSF

-

- MSF’s Munira Gulomova conducts a mental health consultation with Akmal Uganov, 25, at his home in the city of Tursunzoda, Tajikistan. Uganov fell ill with tuberculosis (TB) in 2019. “At first, his mother got tuberculosis. She was ashamed of her illness and didn’t seek treatment. As a result, she passed away. Her father also died of tuberculosis,” Dr. Maysara Shifoeva, MSF staff says. MSF started to provide support to Uganov after the death of his parents. It included monthly medical check-ups, medication, food, and psychological support to ensure effective treatment. ©Natalia Chekotun/MSF

Decolonial perspectives

Every photograph in this exhibit was created by artists rooted in the places where we work. It includes 30 photographers from 22 countries. These photographers embody decolonial perspectives by having ethnic, cultural or linguistic connections to the

communities they portray, as compared to a traditional photojournalist on assignment from abroad. The images were selected in collaboration with colleagues around the world with similar origins or identities, including leaders in our DEI and anti-racism efforts.

Questions to consider while viewing these images:

- Does the image convey dignity and respect?

- Who is centered? Who has agency? Who takes action?

- Would I want myself or a loved one to be shown like this?

- Does the image create distance from or nearness to the people shown?

-

- Short caption: Ahmet* in her rooftop apartment in Mar Elias, Beirut. She travelled from Bangladesh to Lebanon to find work eight years ago. ©Myriam Boulos/Magnum

-

- After finishing Sham’s dressings at the MSF clinic in Gaza City, Belal made her a balloon out of gloves and wrote her name on it in Arabic. ©MSF

-

- Zulfa’u Musa bends looking at her daughter Safiya at the ITFC in General Hospital Zurmi, Zamfara state, Northwest Nigeria.

-

- Mr Yurii has been in hospital for a month and a half, following a mine-blast injury that resulted in amputation. “I was in trauma for a month, trying to save my leg, but the infection was severe. Initially, I was very worried, but I accepted it. They showed me how to train and the types of prostheses available, and I realised I could walk again. Now I’m actively working with MSF psychologists and physical therapists. They listen, offer advice, and bring me interesting books. I enjoy historical and professional ones; the last ones were about Genghis Khan and the Cossacks. I still want to learn to drive, so I have work ahead of me.” Mr Yurii is focusing on balance exercises to expedite his progress with the prosthesis. ©Yuliia Trofimova/MSF

-

- Maya [name changed to preserve anonymity], a Syrian refugee in northeast Lebanon, holds a dove she tends to in her family’s tent in Arsal. The journey into Lebanon is etched in the memories of those like 21-year-old Maya, whose harrowing escape is a testament to the horrors endured. “We arrived at night, under constant shelling,” she recalls, the trauma of that fateful journey still raw. “We arrived in Lebanon at night in a car. Many of the wounded were with us, some had undergone surgery, and others had lost their legs. The scenes were terrifying. Most of us were children. My sister and I were placed in a car with wounded people. One of the wounded was my uncle, covered in his blood, with his wounds exposed, his eye gouged out, and his leg amputated. This scene will never be erased from my memory.”

-

- MSF physiotherapist Ahmad Alrosan gently stretches the muscles on the hand of a patient who had a broken wrist and whose right finger was amputated. ©Hussein Amri/MSF