Following decades of persecution, culminating in ethnically targeted violence in 2017, over one million Rohingya refugees in Cox’s Bazar have carried an unbearable weight of displacement, violence, and loss. While physical wounds eventually heal, psychological distress is a deeply persistent challenge that continues in the face of ongoing trauma. For Rohingya, life in the camps is marked by restricted movement, aid cuts, scant opportunities for education or work, and violence within families is not just difficult; it is an ongoing cycle of trauma. The deepest pain comes from the crushing absence of any future hope. The systematic revocation of their citizenship rights in 1982 stripped the Rohingya people of all fundamental rights, making them stateless, creating a cycle of trauma and leaving them trapped and utterly without control over their own lives. This limbo is a continuous source of suffering that demands specialized support.

Stigma remains one of the biggest barriers to care.

The chronic trauma of a life in limbo

The scale of initial trauma continues to haunt Rohingya refugees in the camps. Mohammad Faruq, who worked with MSF’s mental health team to develop health promotion materials, recalls the terror of his journey from Myanmar’s Rakhine state in 2017, “we had to see things we had never seen before. We had to cross rivers and streams in fear. My siblings had never seen a river before. The boats were very small; the weather was stormy. It was terrifying.”

Thousands of refugees, like Faruq, live with these harrowing memories while facing the daily struggles of camp life. Their suffering is magnified by a life of forced containment that cuts them off from education, work, and any movement outside the camps and the devastating knowledge that, as people denied the right to citizenship, they have lost all power over their own lives. This profound lack of agency, combined with uncertainty, continually wears away at their mental well-being. As Faruq explains, to move forward, one must confront the pain, “If I stay silent just because I have suffered, it won’t work. I must talk to someone else and ask for help from those who can show me the way.”

Many suffer in silence, yet community initiatives are helping break that silence.

Finding healing through art

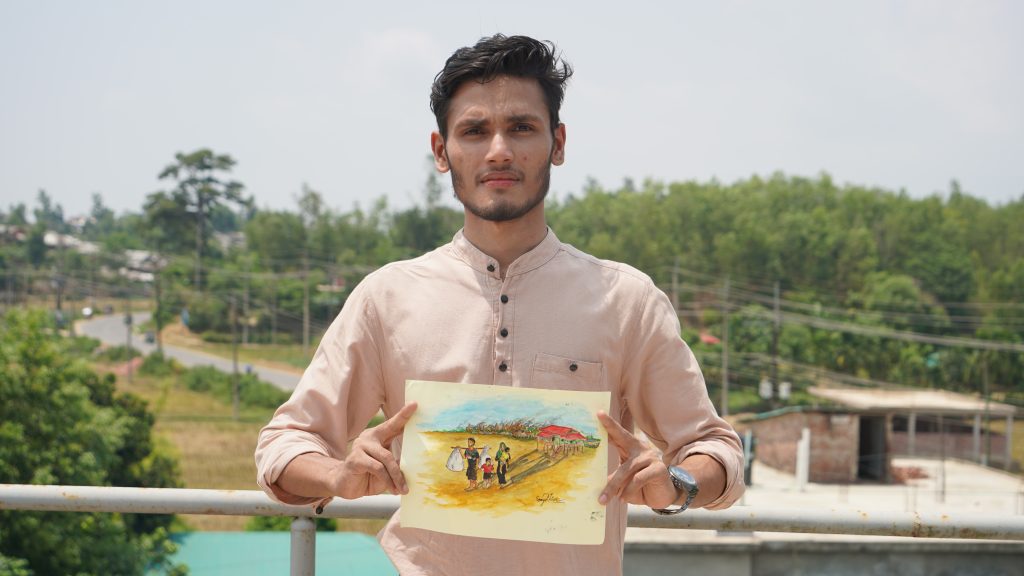

For Enayet Khan, art became a way to cope when words failed him. He describes his turning point after arriving in the camps, “after 2017, when we fled from our country, I couldn’t find peace. I felt restless. I didn’t feel like sitting anywhere. Then I thought, I have a talent. I started drawing. At first, I didn’t know what to draw. But then I thought, the world has not seen what we went through. So I began to draw those stories.”

His art became essential for survival, shifting its purpose from simple pleasure to urgent necessity.

His artwork, the scenes of burned villages, families in flight, and the quiet resilience of his community-quickly drew attention. “Through art, I can explain the stories of my community better. If ten people speak instead of one, the message spreads further.”

Breaking the silence – the necessity of specialized support for Rohingya refugees

Both Enayet and Faruq have stepped into supporting others, an initiative MSF facilitates through art and painting. Faruq’s commitment to his community is clear, “The Rohingyas who have suffered and been victims of violence or trauma need treatment. I accepted this offer from the mental health project to help them, putting my own pain aside.”

To strengthen this support, MSF trains Rohingya community psychosocial team members to share information in culturally meaningful ways. “For those who are really struggling, the distress is high, regardless of the coping mechanisms. For these people, we also offer specialized mental health services. We work directly with Rohingya volunteers, teachers, and community leaders,” says Ioannis. “With the help of visual materials created by Rohingya artists, they spread messages and have discussions around coping, resilience, and mental health. Our aim is not to change beliefs overnight, but to increase knowledge and show people they are not alone, and support exists.”

Mental health care is often overlooked due to stigma, yet for the Rohingya in Cox’s Bazar, it is as vital as any other medical service. Through the courage of community members like Faruq and Enayet, and the dedication of MSF’s teams, spaces are created where people can express their pain, find connection, and move toward healing and coping. As Enayet says, “Many people cannot bear the pain they carry. If we talk, if we create, if we share, our hearts feel lighter. That is how we begin to heal.”

"In our minds, we always carry our country, our home, our land.”

— MSF South Asia (@MSF_SouthAsia) October 14, 2025

For Enayet Khan, art became his lifeline when words failed him.

Through his artwork—Enayet found a way to process his pain and amplify the voices of his people. “Through art, I can explain the stories of my… pic.twitter.com/mKDCpS2TBy