As donors meet in Brussels to pledge funds to assist the Central African Republic, MSF is calling for renewed commitment to the country. Premature disengagement or a de-prioritization of humanitarian aid to the Central African Republic by donors would have catastrophic consequences for people in CAR, one of the countries with the worst health indicators in the world, where armed fighting is still prevalent and 20 per cent of the population are refugees or internally displaced.

Emmanuel Lampaert, MSF’s country representative describes the ongoing crisis in CAR and an urgent need for continued donor support.

On Sunday, three weeks ago, our little maternity of Gbaya Ndombia was overrun by the victims of the latest gang fight in the Central African Republic’s capital. Our midwives, whose job is to bring healthy babies to life, had to stabilise 12 men severely injured by gun shots, rockets, and grenades while reinsuring and coaching frightened moms-to-be in labour. Three dead bodies, including the leader of the main illegal armed group from the neighbourhood, were laid in the maternity, between a poster about breastfeeding and another about contraception.

The events of this Sunday were extreme, but not unexpected nor unusual: whilst the MSF maternity ward opened earlier this year to safely bring babies into this world, half of our midwives’ activities nowadays are spent working as first responders for male victims of violent trauma who have nowhere else to go. Before this Sunday, we had been especially busy stitching up traders from the nearby market. They’d been clubbed on the head for having failed to pay the daily “tax” of 100 CFA (about 15 euro cents) to the armed groups who control much of the economic and daily life in the neighbourhood.

The Central African Republic is not in the midst of an all-out war though. In fact, the general elections held last March were supposed to close the latest chapter of acute crisis that peaked in 2013 to 2014. It does not mean, however, that deep-seated humanitarian problems have been solved. For example, the reason why dead and wounded arrive in our maternity ward is because it is the only health structure open 24/7 in the PK5 neighbourhood, where most of Bangui’s Muslim population lives. This is a testament to how unavailable health care is throughout the country: we’re in the heart of the country’s capital. In some many rural areas, the situation is even more dire.

Our organisation, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), runs 17 projects across the country. Last year, we provided over a million medical consultations in CAR, a country of 4.9 million people. This was made possible by the generosity of our private donors, who allowed us to spend $58 million (55 million euros) last year to provide healthcare in the country. It’s a large sum – the third biggest budget for MSF – but this barely represents an investment of $11 per year per inhabitant. And still, it’s more than what major institutional donors have spent to help the people in CAR in terms of access to urgent and basic health structures and services, and it’s much more than the entire budget of the CAR ministry of health. And the future does not look much brighter. Fatigue has taken hold of donors. The current donor conference aims at raising $16 per year per inhabitant for health for the next five years, barely more than what MSF alone invests, and in a country where basic healthcare is extremely weak if not, in some parts of the country, virtually absent[1]. In 2016, barely a third of the budget needed to cover humanitarian needs has been funded. Donor countries have been reducing their funding, which directly affects other NGOs that, unlike MSF, rely on public funds and are therefore forced to diminish their activities. Bambari, in the south of CAR, is one such rural area that is particularly vulnerable to the swaying commitment of external organisations. It is literally divided by fighting, often flaring up on either side of the main bridge separating the town.

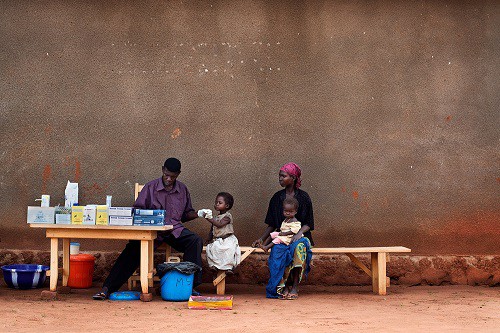

cases in the community so people don’t have to travel to

the hospital. Here, a two-year-old girl is tested in the Rosin

neighbourhood on the outskirts of Carnot. Photo: Jacob Zocherman

In July this year, our programs in Bambari had to be increased, after an international charity with a key presence in the region was forced to make the difficult decision to pull out of the Central African Republic. The announcement was attributed to the ongoing conflict along with high security and operational costs and a frail donor environment. The withdrawal would leave Bambari with huge gaps in health care: and a regional hospital with effectively just two doctors to care for an estimated 55,000 people. The sad truth is that this scenario is not just unique to Bambari, it is being replicated right across the country, particularly in CAR’s regional areas.

It’s difficult to describe what it is like to live or survive, without healthcare. Recently a patient came to an MSF field hospital with a wound so advanced that all the flesh on his toes had been eaten away, and his bones fell off when the nurse tried to clean it. We tried to refer him to a hospital, but that was much too late: the patient, who was HIV positive, died within two days. Despite his horrifyingly severe wounds, causing immense pain, he had never consulted a doctor before, because he could not afford the few dollars fee asked from him in the cash-strapped public clinics.

The Central African Republic may have passed the latest peak of a decade-long crisis, but it does not mean that things are “normal”, when “normalized” is the presence of active armed groups in different areas of the country, prone to periodical outbursts of violence that cause more people to flee their houses, more displacements, more fear and disease, more difficult living conditions and less access to health structures or basic services. The CAR crisis will not be solved by itself. In fact, if CAR was one of our patients, we could say that it’s out of the emergency room, but still needs to be kept under perfusion in intensive care. If the donor community were to pull the plug now and cut funds to the country, it would be like discharging it much too early. This would have tragic consequences.

[1] France, for example, invests 5.000 euros on health per year per inhabitant